MC: Your work is looking at absence, and about looking at these objects which represent something which is not there. That feels like something which would be difficult to wrap your head around. How did you approach this in the first place?

LP: A lot of my work came into realisation last year when I wrote my dissertation and realised what I actually wanted to make work about: writings on early language, on cuneiform, on the rift in a long period of time and seeing the evolution of something which is a representation of a physical thing. And that writing will always be insufficient, writing will always be an in-between point, and that sort of acting as a metaphor for things that are lost and all these ungraspable things – you can always write about it and become closer to it in that way.

MC: So are you looking a lot at Derrida, and the sign and the signifier, and that kind of thing?

LP: I have, yes. And Barthes I guess. But it is steeped – and a lot of semiotic theory is steeped – in a very western male dominant history, where it is difficult to form a rounded overview of what writing is or what signifiers are. But I will not deny that I am really interested in semiotics, yes.

I came across this artist through one of the contemporary art lectures by a curator [Eugene Yiu Nam Cheung] who created a show at Whitechapel Gallery on Anna Mendelssohn [Anna Mendelssohn: Speak, Poetess, 11 Oct 2023 – 21 Jan 2024]. She was a poet and activist during the 60s I believe, and I connected with her work on ideograms and how you can use writing to protest, how you can use writing – and line generally – to fill this gap.

MC: What is the gap that you’re talking about? Is it the gap between what we see and what we understand?

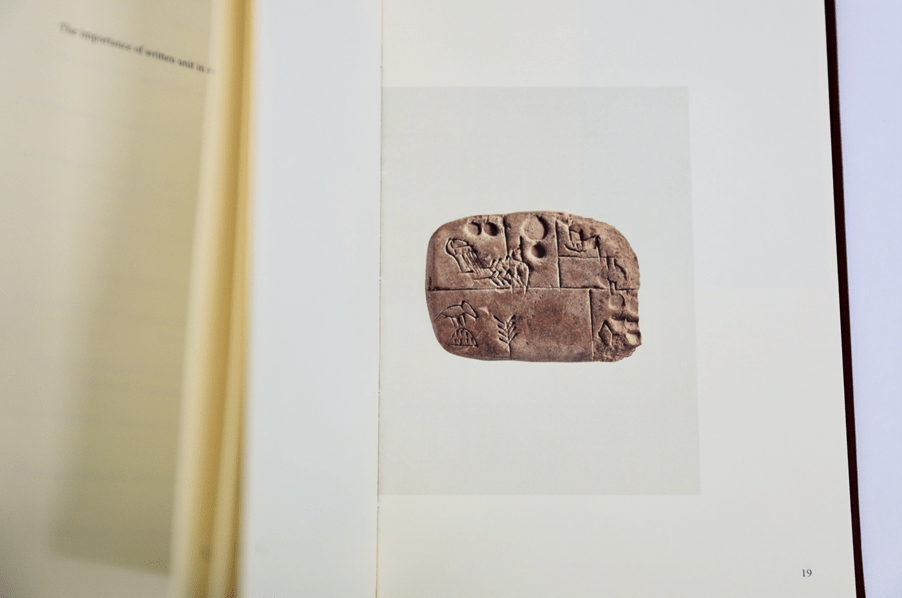

LP: Yeah, I guess the gap between the physical thing you’re trying to depict in writing, and the writing itself. This sort of stems from the research on cuneiform. So, written script first started as tokens, in Mesopotamia, and the Assyrians found that they could print the tokens into clay. The tokens were originally made of clay from the banks of the rivers Tigris and Euphrates, which encircle Mesopotamia. So, these tokens could be printed onto clay to further record their life…

MC: So, like a record, or receipt of the coin?

LP: Yes, it is a record of the coin, and then those records, those indentations, became pictographic drawings. I’m interested in the gradual evolution of recording and the sort of losses between those shifts, because you are getting further and further away from the origin – the original impulse to record.

I think I met this tension in my work as well, in these changes – are they more true than the origin of the need to record in the first place? Or are they by-products?

MC: I see what you mean. I think that was the reading I had of your work on Greatorex Street – the sound piece. You take something, and then you translate it through different layers of recording to produce this sound. I’m not sure what processes you used with it – it seemed that you had some very complex ways of recording the original sound and seeing how it changes. And the thing that that becomes – is that authentic, or is it a whole new thing?

LP: Yes, definitely. For a while, with the recordings, taking it from the wax cylinder to the digital was a step which I would not want to do for a while, because I really didn’t want to take it away from its original form. But there is so much to that progression of making it digital. There is so much breadth to it, it goes so much deeper – like if it is digital, it can go anywhere, but it is so stuck if it’s just on a cylinder.

MC: This is so interesting, and it really chimes with … do you know Stuart Hall?

LP: Yeah, I do.

MC: Did you ever read his essay ‘Modernity and Difference’ with Sarat Maharaj? It is a conversation about the untranslatable and travelling culture. There are always things which are not able to be translated when you’re moving around… like if you are a diasporic person trying to translate your culture to become understandable to someone else. There’s always things left behind, which cannot be understood – and these untranslatable things are what make a culture a culture.

I always apply the idea of translation to ideas of cultural identity, but I think it does apply to lots of different things. And Stuart Hall talks about Derrida, and he talks about a sentence that is ongoing, where meaning is always deferred down the sentence. That’s why dialogue is really important in culture and in art – you always have to be in-dialogue with the thing that came before, because when you put a full stop in the sentence, you are fixing meaning at a point where it is incomplete. That is why I think art is really important because you are having a dialogue with things and you are opening up conversations which would otherwise remain… unsatisfying, stuck.

LP: Yeah, it allows for the visual progression where words can’t fill in – I think that is what I like about art the most. But at the same time, writing and speaking- it’s this secondary system that we have compared to seeing and feeling something visually. It is a translation which is never quite sufficient, but it is the closest we can get, and the best that we can do. I’m always thinking, how can we get closer? How can we get closer to translating the original thing best? I think that is why I am really interested in pictographs and signs and signifiers.

MC: So I was looking through your work on your website and Instagram, and it seems to me that in your work you have a fear of forgetting. I was wondering if you could talk about that, maybe, why forgetting is such a big thing for you. Or rather, capturing something so that you don’t forget it?

LP: I think… it is just a fact for me that recording is so important. Capturing as much of the truth as possible – whatever the truth is. Trying to get as close to reality – and the whole picture – as possible. Recording has a sense of care instilled in it as well. Trying to do justice to the thing, trying to translate, whether that may be a moment in history or a conversation… I think definitely, at its core, my work looks at how recording can outlive the body, how it has this capacity to elongate a life either in writing or in sound. I think that is so beautiful. There is an element of longing, I guess, to not forget.

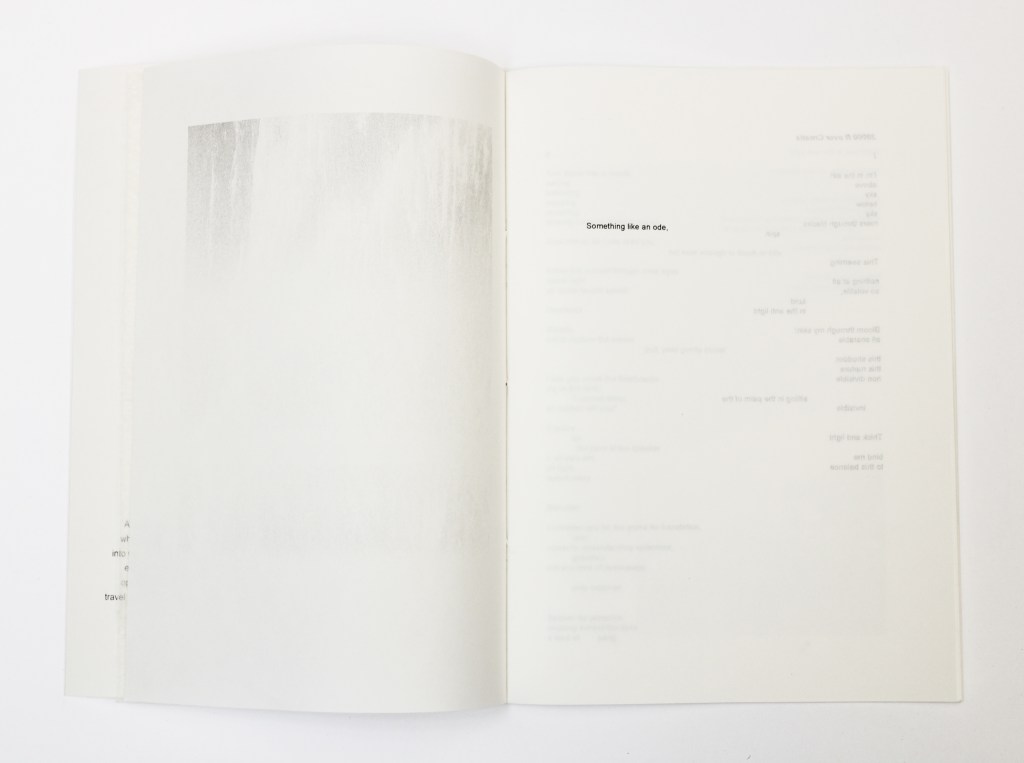

MC: That’s a really intimate and sweet way of thinking about it. I suppose, on the personal level, we are all trying to record things before we lose them… thinking about the people that you care about and trying to save things for them. I was thinking of your work, ‘Heir’ – is that what that was about?

LP: Yeah, definitely, I think that came from a point of my first real interaction with grief, and it was out of fear… it is very personal, that work, and very tender and close to me. I lost my grandfather, and it was just a very difficult time when I was very afraid of losing another person in my life. There was this need to hold a sense of hope, to hold something physical. The writing and the image felt very solid in that way. It was a very tender piece of work, and I am hoping to write another edition.

MC: I hope so!

LP: There is one copy bound with my hair, which was really fun to do. I’ve been wanting to bind a book with my hair for a long time.

MC: All of your books – you can tell all the care that you put into them. The way that you choose materials for these things, like the Bible paper, really stood out to me. There’s also this graphic etching onto paper you do, rather than writing…

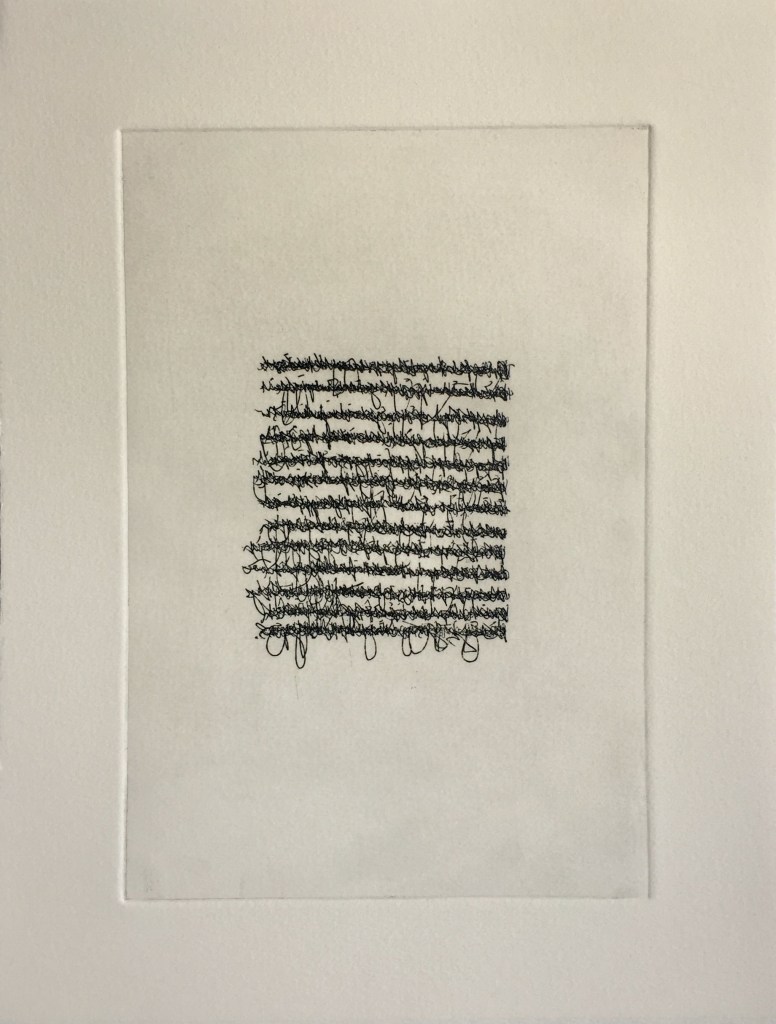

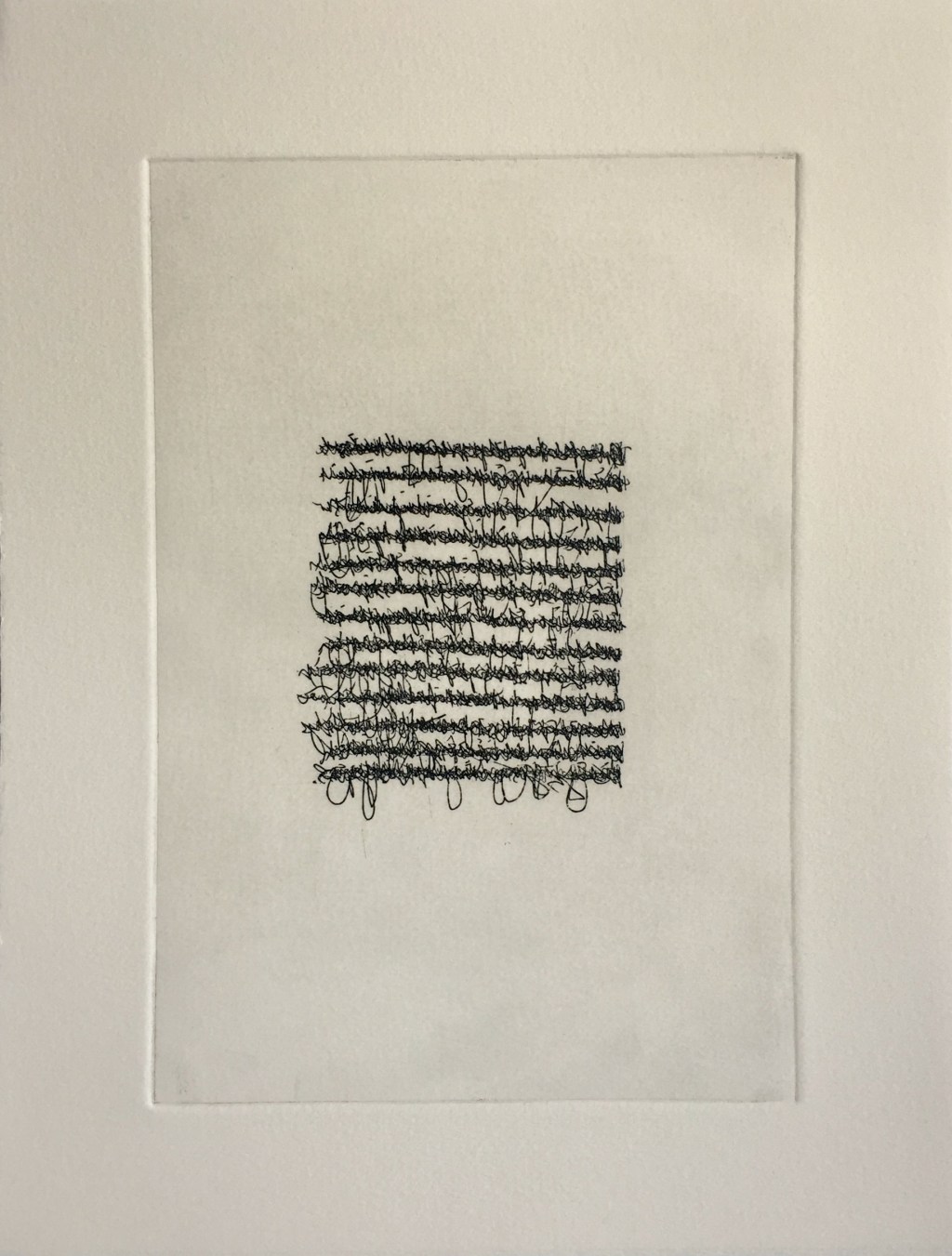

LP: I did a lot of etchings in first year actually. I did one in collaboration with Nisha Gahani. They’re from Lahore, a school in Pakistan. That was a partnership programme – it was really great, one of the best things I did in first year. We were on Zoom, and we were really well-paired because we were both making work about translation. They were doing a lot of writing in their primary language, and going back to their mother tongue. They were doing writing exercises, and at that time I was also doing a lot of writing exercises and a lot of continuous writing and trying my best to record. Also thinking about the failure to grasp things fully. I made an etching out of that conversation.

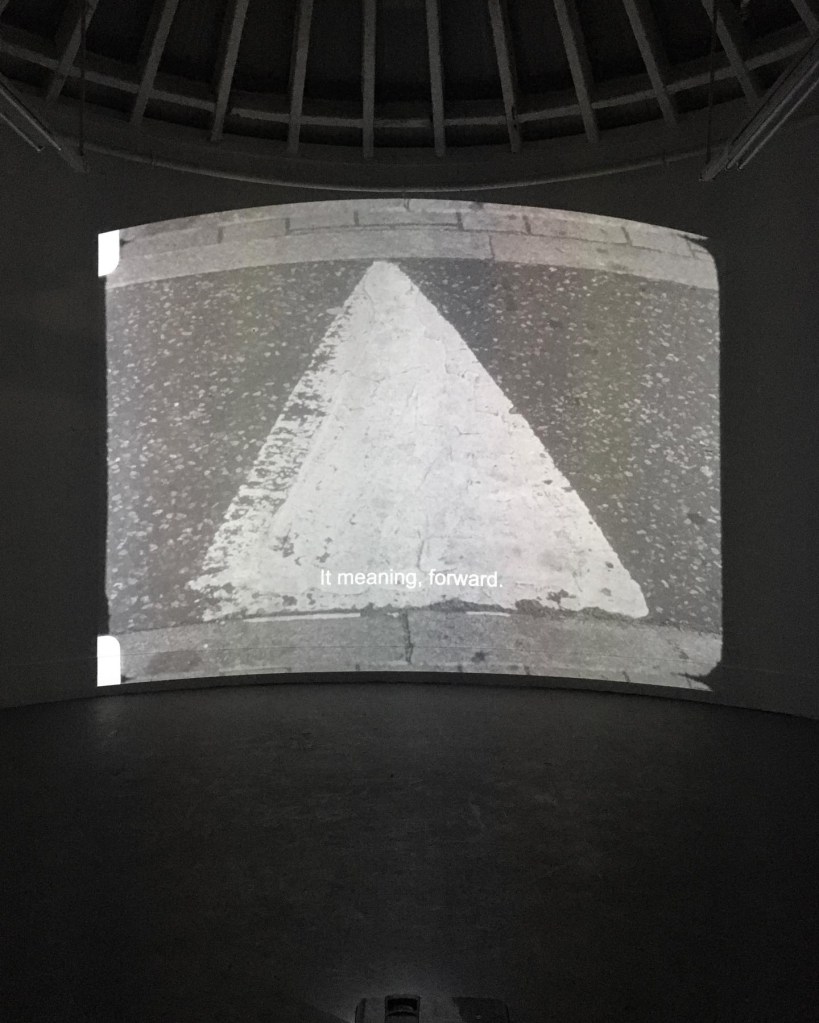

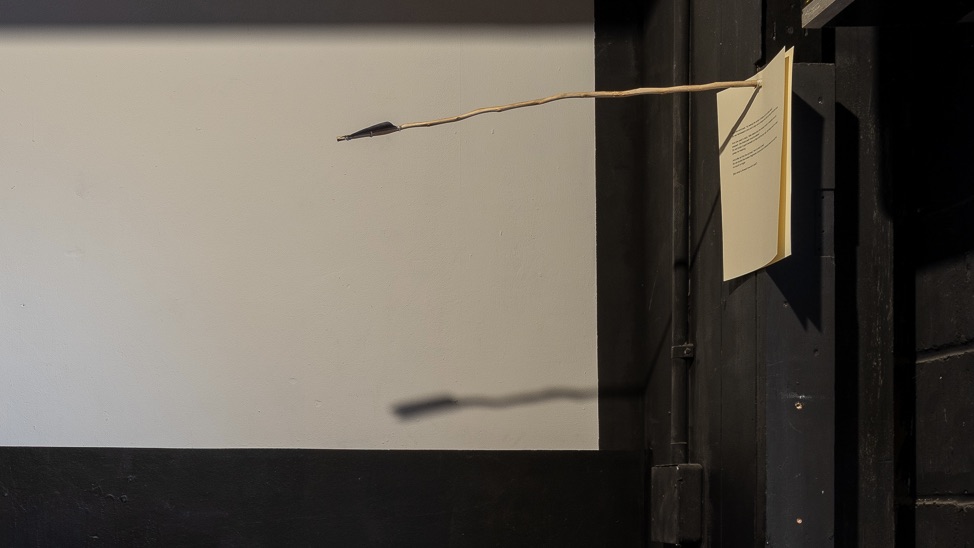

MC: I also wanted to talk about the arrow. To go back to talking about signs and semiotics – I am also a big fan – I think your focus on the different types of arrows was super interesting, especially in the Greatorex Street work. I saw on your Instagram that you are doing a lot of work with arrowheads, and also the arrows that are on the road – street-markings and such, especially when they have been half-erased. I thought that was interesting. Why did you choose the arrow, first of all, as your sign of choice?

LP: It was originally very instinctual. It is a visual that has really stayed with me, that is sort of unshiftable because… there’s nothing quite like it. It also relates to rifts of time, as well, and cuneiform.

The word ‘arrow’ in cuneiform is interchangeable with the word for ‘life’. I thought that was so interesting. And a lot of the wedges in the later artifacts where the script becomes logosyllabic – they are all arrow-shaped wedges. So that sort of permeated into my work.

Primarily, I was thinking a lot about tools, and the evolution of the arrow as a sign. So firstly, the arrow as an object, as a physical tool, is a weapon used to kill. I was looking at its original use versus how we would encounter it, from my experience, on roadways. We now encounter it as a wayfinding symbol, which is helpful, which is non-harmful. And that rift between a harmful symbol and a non-harmful symbol – but how it has kept its form – is really interesting to me. That shift, that sort of more minimal representation. The whittling down is also interesting to me. But through its evolution it has kept its flight metaphor. It is a symbol to progress, to go forward.

MC: Did you ever read the Carrier Bag Theory of Fiction by Ursula K. Le Guin?

LP: Yes! I love that text so much.

MC: I was thinking about that text, and what it says about spears and arrows and how they are thought to be the first sign of civilisation. But then actually, she says, probably not. But it is a certain type of… well, she calls it a story… but a certain model of civilisation that we still have, where everything has to be going forward all the time.

LP: And the heroic, from the feminist perspective – this male, heroic, forward-projector, which I think has permeated. I am thinking of Derrida and sign, and you know… it comes through. I think she writes wonderfully.

MC: Yeah. It is such a funny text, too. I love the image of her as a bad-ass old lady with a handbag, picking off the idiots.

LP: In the soggy oat patch, with Oom taking down the mammoth… I’m reading ‘Always Coming Home’ by Ursula Le Guin at the moment. It’s a fiction about this civilisation called the Kesh, and they don’t exist yet. She’s telling the story of the Kesh and it’s a whole contained world in itself. She’s telling the story of a civilisation that hasn’t existed from the future – sort of thinking about the arrow, and evolution, and looking back – the past and the future being pulled together. And what I’m trying to hint at with the arrow is really the premise of the book.

Also there’s something about the arrow that I find deeply sad and futile. It is a symbol that is promoted for forward progression, but in itself, as a body, it will never move. It will always be stationary. I know it’s sort of a silly thing to say, but there is something sad and futile about this sign which used to have this… I don’t want to say masculine strength, but in relation to the Le Guin text, yes… becoming this traipsed-over sign which serves people.

MC: Is that what you were talking about in that film you made with the street markings?

LP: Yes. That was the origin of the Greatorex piece too.

MC: If that is your most recent exploration, what are you thinking next?

LP: I’m trying to make a roundabout in the quad at UCL! I’ve sent the proposal, hopefully it will be allowed. I’m going to try it out for my crit, and then if it works well, maybe put it into the degree show. Also at the moment I’m trying to do another edition of books I made at the start of the year.

MC: I can’t wait to see that. Ok, right at the end, I wanted to ask you for three names of names of people – your contemporaries – who have an accordance with your work or that you are just a big fan of, who you think I should go and talk to.

LP: People who inspire me… I’ve been really interested in Jonathan Callan. His use of material – he makes books a lot. He’s really playful. I think he went to the Slade for his MA in the 80s or 90s.

MC: How about some of your colleagues?

LP: Whose work I really like? There are so many. Everyone in ‘Rift’. Definitely Ed Burrel. He works a lot with the archive, and I think you’d really like his work – the queer archive, and family history, and lineage. Also, to do with archives, Rebecca Stenfors. She went to a city in Finland, she travelled and made this film… it was in ‘Rift’, the film in the corner. She made a story based off her journey to locate this English boat located in Finland. Also with the archive, Jem Crook. He was also in Rift, he’s at Slade too. He works a lot with his Irish ancestry.

MC: Oh, is that the film with the objects in the room? I really liked that one.

LP: The film with the objects. I really, really love his work, and I’m really excited for his degree show.

MC: Amazing! Thank you so much. It’s been lovely hearing you talk about your work.

Leave a comment