MC: So where did it all start?

SGS: This railway arch in Clapham Junction behind the station. It was actually part of the train station, and that was my first ever studio. And that was the first time… you know, you put yourself out there a little bit, to see what happens, and you start calling yourself an artist.

MC: When did you first start making art?

SGS: I’ve always made stuff, drawings. I was on the streets for quite a while, and I met this guy down the road. He was a severe paranoid schizophrenic, and he said to me ‘I do these drawings, do you want to come and see them?’ We just used to hang out and talk about art. At that time I was drinking heavily and I was on the streets, but I always knew that I wanted to make stuff. Before that I had been a technology guy, computing, sales. It just wasn’t really… you know? In a sense, now, if I articulate it… art kind of saved me.

From about 2005 I was in capacity or another making something. I just didn’t think of it as a job. Then it started becoming something where I could earn a little bit of money – because I was unemployed then. I did a film with someone, who thought that making films was all about big cameras and big crews. And I was like, no, all you need is a PC. That was probably my first paying thing.

And so, as my life was going further down, my education in art was going up. I just talked to this guy about art – mainly about Vincent Van Gogh – for four years.

MC: That’s a good education! But were you seeking out other books? I can see you’ve got loads of art books in here.

SGS: Yes, so me and him, we collected stuff… Kippenberger… any drunk artist! He died, but I actually kept all his things. Me and him published a book – we didn’t want to sell the Big Issue, so we decided to publish our own book. He had about £3000 and I found somebody to print it for us, and we would sell it. But not in the typical way, just to make enough for whatever we needed that day.

There were a lot of people who were opting out of normal life – like work, paying rent and stuff. It was the freedom, and I could devote myself to art. So I decided to clean myself up. The big decision then was what do you do? Do you get a job, do you start sweeping the streets? That’s what I thought I would need to do, but for some reason, I think I came out of that bad experience an artist. People just treated me as an artist. Some guy asked me to do a logo for his company. I though it would be a fifty quid job, and he ended up paying me a couple of thousand. And then I just thought ‘oh, you can live on this!’ So it was both a decision, and not a decision. But I was always conscious that I wanted to make things.

MC: I wanted to talk about the work, and your interest in art history. I mean, you can really see the influence of French Impressionism, but also the influence of people like Lucien Freud and Kathe Kollwitz, and plenty of others.

SGS: I came to art by looking at pictures in books. That was my formal training. From a very young age – Biblical images. That was how I got introduced to what painting looks like, these visions. Now I realise it would be more like Reuban’s style, or Titian’s. So my idea of art is through the Western eyes, through Western painting I suppose.

MC: I was going to ask you about that. How do you feel about the idea of being part of a canon?

SGS: I actually embrace it, because painting as such – whether you are looking at Chinese painting, or African-style making – painting itself is more a Western tradition. I like it for that. I stay within that. Even the Africans or Black Americans making painting are still a part of that. You are either trying to break those rules, or you are not educated enough in those rules, and you think you are doing something new but actually it has all been done before. That is a real deep interest for me. I mean, going back to Greek painting – the earliest painting – where the rules were set up. In African traditions of decorating something, you don’t have representations of the face or the body as it is. They are all kind of pulled apart, which is very interesting.

MC: And also with Arabic and Islamic art, as well.

SGS: Yes, I mean there are some interesting Iranian and Persian miniatures which I collect – a different kind of storytelling. Or Indian paintings, very different. But there are a couple of people who I always go back to. Obviously Titian. I must have read a list of painters which I memorised, and these are the people I go to.

MC: I see. And when you are creating a painting which has… I would say more than a nod… to a certain painter, do you choose indiscriminately? Is it just what strikes you, or are trying to make a comment about art history when you are choosing your references?

SGS: No not really. I think that is a topic after the fact. It is almost a kind of new way of looking at things, maybe since the 1970s, 80s, where you have to have a critical eye. You don’t just make something for the sake of making it, you’ve got to dress it up as something else. I also think it’s because you might have not very strong ideas, so if you make something you try to give it a story. That’s the way we sell things.

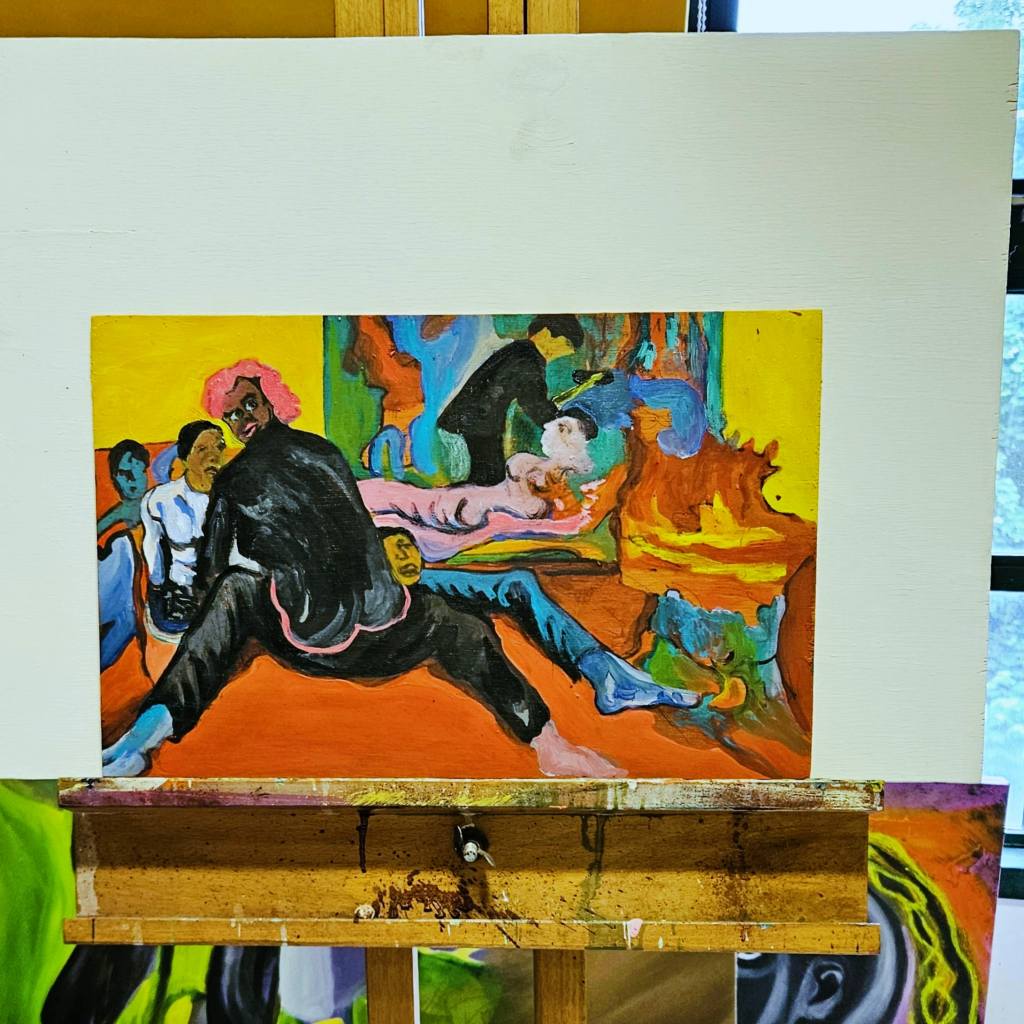

So no, I don’t make things thinking I am going to rebalance gender, racial or other issues. First and foremost, it’s about learning. So I’ll be looking at something – at the moment I am looking a lot at Ingres, and trying to work out what he was trying to do. Lucien Freud was learning from him. And so in my studies of those people, I’ll end up making a painting.

I think sometimes it is almost a titling thing. I’ll be working on something and thinking about an artist, and what they were trying to solve, and I try and put my painting into that context. Very rarely have I made a painting based on a particular reference. Sometimes I will go back to a specific painting, in terms of its place. Maybe it is pivotal to something which changed in art history. But I think the stronger I get within my own work, the more I am moving away from that to more sort of having conversations with these artists. Almost imagining them being in the room with me.

You mentioned Kathe Kollwitz. When I first discovered her, it was because the bodies were sort of bent, and the babies… I thought maybe I could put my stuff in that context. But I didn’t have anything to do with her then. Actually, the way I came to her was through Raphael, ‘Madonna and Child’. The painting which I’ve done is not here – this is a study.

MC: That’s amazing. A pieta?

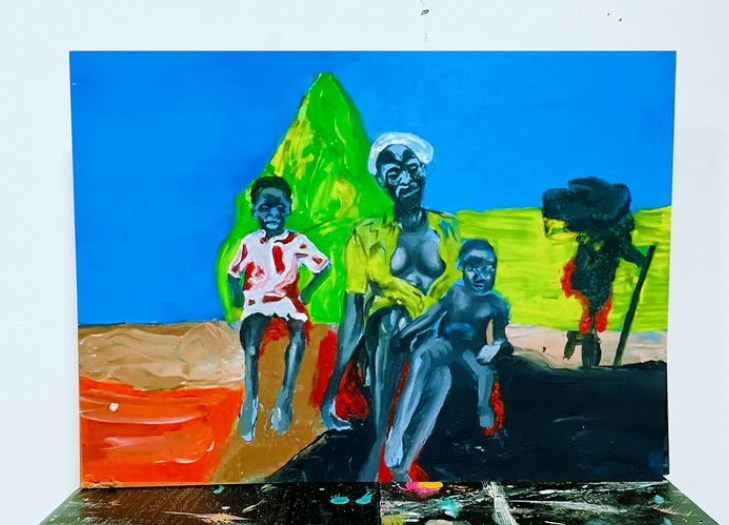

SGS: Yeah, so the actual painting is 180 by 180cm. And also, Jenny Saville is in there. But for Kollwitz, it was about having the mother and child. The context of this is war. When I was developing this, I was looking at pictures of people fleeing – whether in Gaza or the Sudan, or whatever. So my painting is more than a pretty scene of a virginal-looking person who had a child.

MC: And that is what makes Kathe Kollwitz’s pieta so affecting, because it’s so real.

SGS: In the finished painting, I focused on the size of thumbs and limbs and things. There’s a physicality in it. I’m going to make about ten pictures, all similar. But I want to move them all to another level – I want to use them for a campaign. So maybe the Foundling Museum, or some charity that wants to do some work, and the paintings will be my donation. Maybe bring some other people to it, a musician, and then we all make a campaign.

MC: That sounds amazing.

SGS: But I just thought that the way we make things now, paintings are mainly for the market. Let’s say if you’re gay, you will make work based on that. But it doesn’t actually go back to the community of whatever it is you are talking about – whether that’s sex workers, or whatever. You are so removed from it, and the people buying it. I mean, the people in the Venice Biennale right now, they’re talking about foreigners and decolonisation, and all that, but it’s so far removed from the people cleaning those halls and those hotel rooms, who are actually from the countries they are talking about.

MC: Or everyone flying to Venice with their Prada bags to talk about climate change. It’s insane.

SGS: So how can you collapse it back to where the art and the audience benefit?

MC: I want to talk about some of the subjects in your work. How does memory come into your practice? I have heard you talk before about social memory…

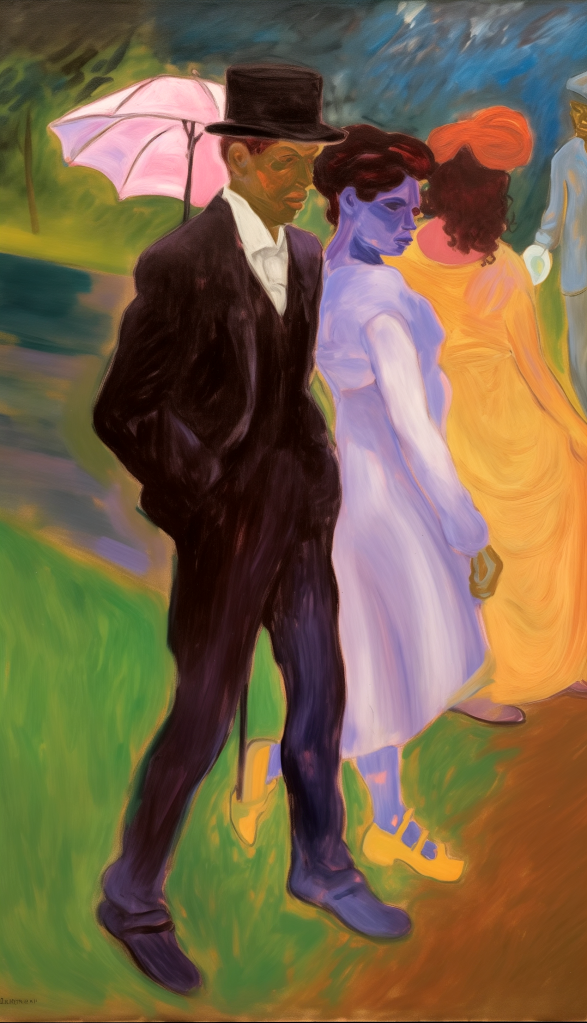

SGS: I remember one of my first loves was always history. It’s the way I make all these connections. It’s not completely reliable or true either. That I also like a lot – fabrication. And just how the brain works, theory of mind. In a way, we make these truths, histories, memories, and then we put them into some sort of coherent presentation. I think because of where the internet has taken us, I try to have all these things collapsed together. If you go to a place now, and you start talking to people about how they feel about the place where they live – on one hand, they have the history of the place and whatever the identity of the place is. So, I’m from a poor area, or there’s no jobs here, or whatever the narrative. But at the same time, they consume the same global stuff as everybody else – be it music, films, or memes. I look at this where I’m from in Malawi – I see them on the internet and they’re making jokes about – I don’t know – Jay-Z and Taylor Swift. That’s introduced quite an interesting thing in terms of how you make a painting. Does a painting live in one particular time? Can it live in different times and have complex narratives? That’s why I can play around with style – these days, with post-impressionism, but putting different bodies in there.

I’m trying to play around with that, and also with how I understand myself. Because obviously I have invented a self, which I am taking out into the world – some sort of avatar. But I have to imbue it with all these supporting structures – schooling, work, histories, all these things.

MC: The great thing about our increased access to knowledge through the internet now is that you can kind of place yourself within an identity more than you ever could before. I’m from a really small village with a strong sense of community, but I think that since growing up with the internet and knowing so much more about the whole world – you define yourself against other things. You say, I am this because I am not that. We are able to do this so much more when we know more about what’s out there.

SGS: But at the same time, you are the curator of your own memories. You have assumed the identity.

MC: Yes, you can pick and choose how you feel. So, it’s a kind of idealised version of my community which I relate to. I know it’s not actually like this, but I like to present a version of it. Like creating a little story-book version of my upbringing…

SGS: …because it’s beneficial. It’s useful to you. And it is those functional aesthetic choices with memory which are, on the other level, used by societies, structures, hierarchies of power, to control. I overheard someone the other day say that history is written by the victors not just so they feel better about themselves, but also as instructions. So anyone else buying into that is accepting a set of instructions of how to behave. You can look at slavery in that way, as a set of instructions that people are still acting out. Whether you are in the Bronx, calling yourself the N-word, or… I work with guys who have been in prison, and one of the biggest things is how to go past that thing of saying ‘this is my lot’. Because you’ve received that instruction. Even though you’re this big guy who could break down any wall, if you’ve got that instruction, when you’re told to sit down you sit down! So that’s the political side of memory.

MC: So do you feel that art is a good way of imagining beyond the parameters of your existence?

SGS: Definitely. From an individual point of view, memory is a tool for you to use to craft your life – but when it’s from the point of view of society it becomes a very different thing. This is where poets become very dangerous, because they are able to do that with a set of words. You can’t kill them.

MC: I think it’s a way of thinking about colonial thought and these colonial systems which you have mentioned in terms of slavery, and the way that we think about gender and race. It is obviously a thing that we’ve constructed but that we’ve naturalised. And I think that the reason why art is so powerful and so necessary is that it can help us to… not even imagine beyond it, but find a new language altogether. I think I can really see that in your work.

SGS: Exactly. If you can’t see it, you can’t create it. If you can’t imagine it, it doesn’t exist.

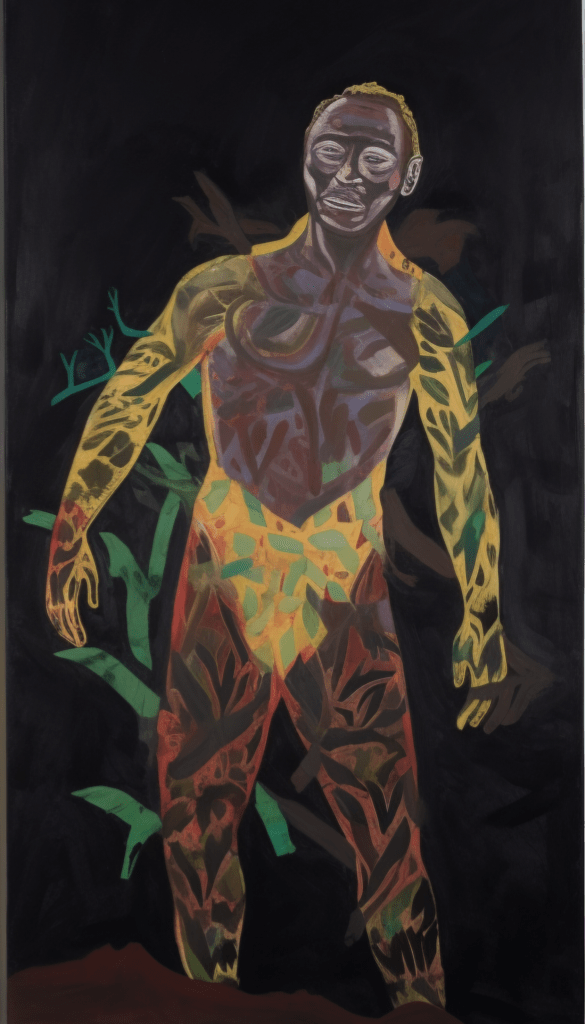

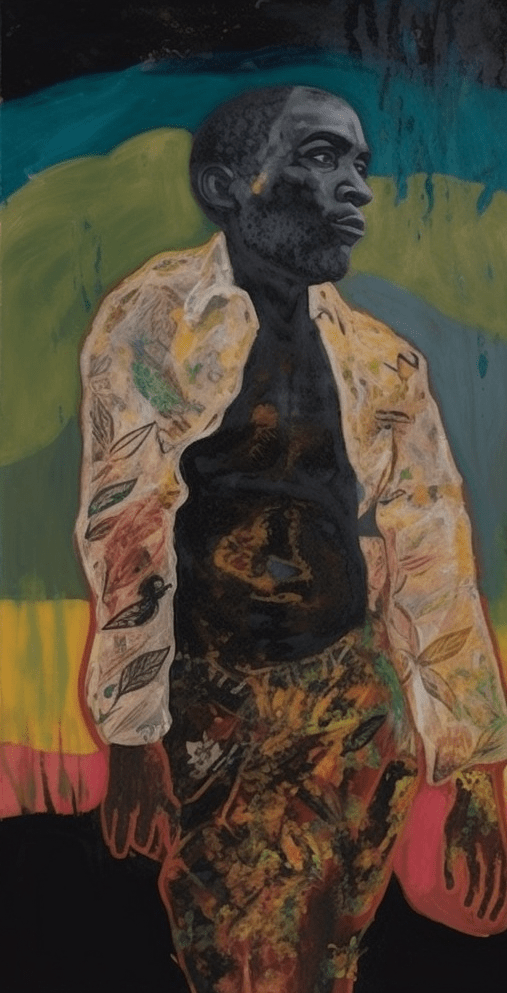

MC: So does the imagination play a large part in your work? I was looking at your ‘African Superheroes’ series…

SGS: Here, I’m constrained by size. The only concept I have is that the paintings have to be at least four meters tall, and it will be a Parthenon kind of idea. In Rome, when you had a general returning from war, one of the reasons why they looted so much was that they would have a heroes parade when they got back to show off all their stuff. Caeser was very good at this. It was this presentation of marching into Rome with your things, the taller the better. That is the idea in my head for these paintings, and I’m glad you noticed it.

MC: So are they imagined figures, or are they based on real people?

SGS: They were once real people. That takes us to an interesting woman, who was the best one at making these sorts of images – at least, Hitler thought so. Leni Riefenstahl. She showed Hitler how you make a heroic image. She did all the films for the Third Reich. She just knew how to place the figure in a heroic pose.

MC: Yes, I mean I can see these images from almost every single presidential election, right? It’s always the same pose.

SGS: When it came to the Nuremberg Trials, she was acquitted. But the ones she did of the marches were amazing. Her brief was to create an Aryan hero and imagine what that society would look like. And they turned to an artist to do that. And she was brilliant at it.

But, after the war, she couldn’t be in Germany any more – she felt that her work was brilliant, but what they used it for… So, if you flip to the back of the book, you can see her second greatest love. She discovered these tribes, the Nuba people in Southern Sudan. The way she photographs them is very different.

My heroic types come from that, and also from some other photography which I have collected from different people.

MC: These works are fantastic because they’re not anthropological at all. That’s a heroic, old-school portrait.

SGS: And it’s done so cleanly as well. They are very special images. What she did do, without knowing it, was capture the last of this particular tribe’s innocence. After that they all got AK-47s and all the rest. The faces and the bodies in my paintings are coming from a bit of that. It is an idealised face. The majesty of it. Playing around with that bit of memory which is being captured, here, in photography.

MC: I see. The same techniques she is using here to create the Aryan hero are being used again later to photograph the tribes. I guess it does just show how much all of these identities are a construction.

SGS: I’m going to use that same level of storytelling and intensity, but I am going to make it truthful, as much as I can. Which I suppose, in artmaking, you can still do. Which is the interesting thing with Rembrandt, this trying to capture something. This is what I am trying to do – whether you’re coming from a public art point of view, or from the other side – so that everything is not so much about funding or exhibitions.

MC: I wanted to ask you about your ‘Holy Mountain’ series?

SGS: It’s a small book with a long title. The whole title is ‘Mount Analogue: A Novel of Symbolically Authentic Non-Euclidean Adventures in Mountain Climbing’. It’s an allegorical novel, written by Rene Dumal in 1952. The story being, there’s a writer who writes a short piece whilst drunk, saying there’s a mythical mountain, and there’s an opening in the mountain that, if you look for it, you can find it. It’s like a quest, but it’s not a real mountain. And he publishes it as a satirical little thing. Then, a few months later, somebody writes to him asking to meet, because a bunch of us are going on an expedition to finds the mountain. And they’re quite serious mountaineers, and they’ve raised the money. And he thinks, well it was a joke, but if they’ve got the money, why not go and try to find the mountain. So they set off to the arctic, and it goes off from there. But it is just the beginnings of how to set up a wide discussion about history, philosophy, various other things that you might be engaged in whilst on a quest for something without your shoes on.

So these Holy Mountain paintings. There are thirty-six paintings, in a way taking the humour from Hokusai’s thirty-six views of mount Fuji. My ones are not as funny – his have some funny details, like a man paddling upstream instead of downstream. So I thought, I could throw all sorts of stuff in there. This one has this famous character from Haitian voodoo and Haitian Carnaval – anyone Haitian would know who he is… Baron Samedi. He is like the death character in most Western mythologies. He’s also a drunk. There’s a lot of drunks… and hats! In a way, through different paintings, you’re puncturing through history. From slaves running off into the mountains of Jamaica in the 1700s, or whatever, but you don’t have things just sitting in one time. It is not easily readable. But they are not puzzles. The Holy Mountain thing is a folly – it doesn’t lead anywhere.

MC: I love that. When you said Holy Mountain it reminded me of Chinese Buddhism and mythology, Monkey King, his trials in the mountain. And also in Greek myths, how the Gods are at the top of a mountain – a real mountain, which no-one thought to walk up to check if they were there!

SGS: That’s also in Mount Analogue. It’s the idea that real mountains used to be mythical, but now that men, women and children can climb Mount Everest, there’s no more mythical mountains. They are replaced with intellectual mountains.

MC: I really like the idea that you are setting up a mythology that is drawn from life, from existing mythologies – and you create the expectation for a moral message, which never comes.

SGS: Isn’t it about what Monkey King learns on his journey?

MC: The best thing about Monkey King is that the mythology gets so complicated and so vast that it ends up meaning almost nothing.

SGS: I think that’s where Mount Analogue ends up going to. And like Jodorowsky, the film director –his second film was Holy Mountain. Obviously, it’s a film that goes nowhere. He loosely based the film on Mount Analogue, but instead of having someone who’s trying to find a mythical mountain, he creates a character who looks like Jesus, and everybody thinks he’s Jesus, but actually he’s just a poor beggar who’s a bit unethical. He’s told that his father lives up in Heaven, so he tries to go up there to get some gold – fool’s gold. But within that, there are all these different histories going on. Like Latin American revolutionary history, the end of morality, and all sorts of crazy things. But he was very good at making images. If I could make images even a quarter as good as him, I’d be happy.

MC: Well, I think that the overall effect of this project, once completed, will give Jodorowsky a run for his money. I’m very excited about this project! I was going to ask you my final question. I wanted to ask each artist that I meet to give me three names of people who are in their circle, or inspiring to them, and who has an impact on their work – like a chain of reference. Living people, contemporaries of yours…

SGS: One who I like a lot is Tim Stoner. He was the first person to give me constructive criticism, and the first person I went to see who was a contemporary painter. Before that I didn’t know anyone. That was only three years ago. And he knows his stuff.

And then the last owner of this studio, Dominic Dispirito – me and him share a lot of things. He’s a natural painter. And Angela Maasalu as well. Me and Angela, we do talk. She’s Estonian. I think that part of Europe, they’re very much symbolic in their visual things and poetry. We exchange pictures, me and her.

Leave a comment