MC: So I read your dissertation, and I really enjoyed it. It made me want to visit one of the caves in Indonesia to look at the cave art.

LW: I’m going to India actually, in November. There’s an incredible cave network in the north of India, called the Barabar cave network. They’re basically these perfectly smooth caves hewn out of the rock, and the inside surface is smoother than modern glass. No-one knows how these were made. The way that sound oscillates in all three of these caves is all at the exact same frequency. They have flat walls and floor, but the ceiling is a perfect curve. It has perfect right angles.

I’m very interested in humanity’s pre-history, its lost or forgotten knowledge. I got into it through reading about the pyramids in Egypt. The whole Giza plateau. Things spiralled from there. I’m really fascinated by advanced technology that we aren’t able to do anymore.

Something that I have been reading about is Medieval organs in Europe. Some of them are so complex that they have 15 to 18 thousand pipes, and no-one can make them anymore. The way they were made, by master craftsmen in Medieval Europe, was that they would drop sticks from high up in the church to understand how the sound echoes. They would let that simmer in their minds, and then could make these specific organs. I am interested in cymatics, and the way that frequency oscillates in these churches is one of the reasons that music in them, regardless of the religious element, sounds so beautiful.

Also a lot of these European churches have copper roofs so they pick up energy in the ether. When you have solar alignments, energy is stronger. There is a long lineage of polyphonic music, people like Thomas Tallis, an English medieval composer. It is very rhythmic and very entrancing. The modern composer, Philip Glass, utilises it when he has these repetitive things. It stirs something. When you have this style of music in a church like that, with an organ like that, with a copper roof, the energy and the frequency build up. There are these sweet spots in the church, where it is completely physically overwhelming being in an environment like that.

There’s this guy called Eric Dollard whose constructed this machine which basically shows you the geometry of this sound. These beautiful geometric shapes, sound made material. It also then speak to this sequential ratio system that Pythagoras developed to essentially understand the way in which frequency affects us. A sort of underground cult part of Pythagoras’ research was to understand how sound and frequency can enter altered states of consciousness, to transcend standard consciousness. This, knowingly or unknowingly, was the underbelly of so much music from Greek pre-Roman Europe up until the 17th century, where it was lost. The knowledge of the organs was lost, the knowledge of the church. Through the internet there is a move to the recovery of this old knowledge. Things are being rediscovered.

MC: It’s fascinating – in your dissertation you talked about how the reason that we have lost our essential shamanic spirit is because of the narrative of perpetual progress – this idea that history is teleological, and it is always progressing towards an endpoint, nothing into something. And the idea that things could have been created and then lost challenges that model of history.

LW: It does. I read a critique of Christopher Ryan’s book, where I actually got that quote about the narrative of perpetual progress. He coined that in his book ‘Civilised to Death’. The criticism is that the scope of the book is slightly limited and oversimplified. However, I do think that the core of what he’s saying in the book is quite poetic. The narrative of perpetual progress very simply states how we are moving towards this never-ending growth, never-ending destruction, never-ending pursuit of more through greed. In doing so, the further we push towards growth and progress, the further we distance ourselves from an original, powerful human existence – pre-civilised existence.

One of the reasons I’m passionate about shamanism in particular is because I’m hyper-conscious of the problems of cultural appropriation, and the way that one could view shamanism through a Eurocentric lens. But I do think that shamanism can’t be isolated to one individual culture. It is the underbelly of all human religion, of all spiritual practices. If you go back far enough, throughout the world, you will find shamanism. I think that’s what ended up honing me in on it when I began to understand it in that way.

MC: This universal nature of this experience is fascinating, even down to the particular shapes and images which you mentioned are shared across all cultures. That blew my mind, when you realise that this imagery is something which goes deeper than cultural conditioning, and it is really something at the very root of everything.

LW: Entoptic phenomena is what you are talking about. It was devised by this bloke called David Lewis-Williams in his book ‘The Mind in the Cave’. He devised this neuro-psychological model for understanding cave art in Europe and South Africa. There’re four stages to it. In the first stage, there is this entoptic phenomena, which is produced by the eye. If you rub your eyes or look at the sun too much, you then get an image engrained in the eye – produced by the body, rather than a result of external influence. The experience of altered states of consciousness – whether that be through plant hallucinogens, prolonged drumming, starvation, or any other physical need – the first stage of that is seeing these geometric shapes. Anyone who has had any sort of psychedelic experience can relate to that. David Lewis-Williams then applies this knowledge of this entoptic phenomena to understanding cave art, and it becomes clear in his research that this is a pretty universal feature of cave art.

In stage two you get forms that you see out in the world – animals, plants and other shapes. In stage three you get a combination of stage one and stage two. Stage four is this full-blown hallucinogenic experience where everything is combined, which is the completed cave painting.

MC: It’s an amazing lens through which to look at any kind of art – trying to find these particular universal shapes, these geometric forms. It also makes abstract art seem a more essential practice. In your studio you’ve got these sketches which look like the entoptic phenomena you have mentioned. Is that how you start a painting, with these basic shapes and forms?

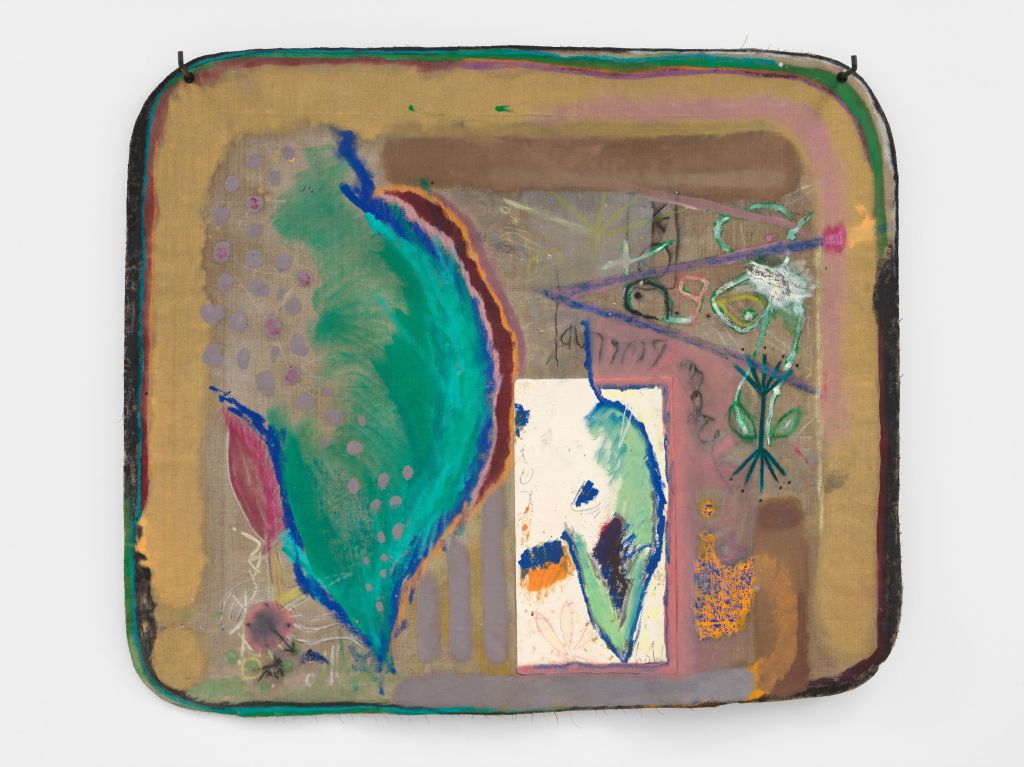

LW: Not necessarily. I’ve always drawn – if something comes to me I just want to get it down so I don’t forget it. But it’s not how the larger paintings start. They might weave their way in – often it will be collage from my sketches which get stuck on. It’s more a way of working through ideas.

In terms of how I begin the larger works, the method is a single idea – a single colour, a single form, and single shape – which gets put down. It might be a wash of colour, then laying something else on top. This single entry point into a work, and allowing things to build from there. I don’t like to have too much of a preconceived idea. The way I refer to painting is a little bit like knitting something inside out, where you don’t know what it actually looks like until you pull it the other way. It’s a backwards process. So much of what I make material, I don’t understand myself. I’m aware of the things I’m interested in, and I’m aware of the research I do, and experiences I have, but when it comes to getting it down in pictures it’s like trying to hold on to a slippery fish. If I hold too tight, when I think I know it, it slips out the top of my hands, and if I don’t hold tight enough it falls out the bottom. I think that leads to that meditative flow state, that links to shamanism, links to altered states of consciousness.

MC: Is that how you feel when you’re making a painting, that you’re in a meditative state?

LW: Yes – at least the idea of getting there. It doesn’t always happen. It feels like it’s such a transient experience that you’re only fully aware of it happening once it’s past. I think fundamentally it comes from a place of relaxation, having fun, being playful, not analysing and not judging things when you’re doing them, allowing that to come later. For me, what happens in my life in the lead-up to painting is as important as the painting itself. You’re sort of tricking yourself into it. A lot of abstract painters could relate to it.

Although I do struggle with that term, abstract, because there are a lot of things that allude to and subtly represent things, and symbology in my work. I feel comfortable operating within this flux-point between abstraction and figuration. That sort of ties in to the sort of person I am, always traversing two worlds, art and music. The way I grew up, my childhood was sort of in-between two worlds, and even where I live, on the outskirts of London. I grew up in the space in-between. In that space I feel most comfortable making.

MC: It is in the space in-between that your work creates a new language, almost. It’s a new language of representation which is not open but also not completely abstracted. I was thinking a lot about your work in the ‘In Rapture’ exhibition at the Bomb Factory, ‘Code to the Organic’. I love that work so much, and I remember you saying that it was about the origins of language. You had almost created your own alphabet system using these glyphs. There’s also little tiny pictures you’ve pasted to the canvas. All sorts of signs and significations which are, in a way, trying to decode the representation of something – maybe the act of representation itself.

LW: Exactly. I’m not providing a definitive language or a definitive alphabet – I’m questioning my own way of communicating. And also, again, it is at the flux point between… where does the curved squiggly lines of letters end and where does this abstract form begin? It is situated somewhere between them. Because the squiggly lines which we would regard as alphabet would have been just drawings before we assigned meaning to them. I’m really interested in that idea, in the limits of language and how we as humans are actually very adept at communicating without it.

Also, some of the forms in that work allude to movement and energy. I’m really interested in the idea that energy is the most real thing for us as humans. It’s an aura we give off. This immaterial plane of energy and sound and frequency, the idea of making that material and kind of combining that with this strange language and having both displayed in the same plane – these are the things that I am dealing with in that picture. But there’s also allusions to symbolisms known and unknown to me. I’m interested in stone carvings and petroglyphs from around the world – particularly ones which are part of lost cultures and lost languages. That’s an interesting conversation to have in regard to cultural appropriation. If a culture doesn’t exist anymore, who does it belong to? I find that fascinating.

The way I see that picture is like, you throw all the elements up in the air, and you take a quick snapshot. Everything’s just in-motion. That’s indicative of how things bubble up. In a formal sense, I was quite conscious of reducing things in that painting. In a lot of my recent work, so much has been thrown in, and I’m conscious of the need to have a bit of restraint and allowing the elements that are there to sing. There’s no background or foreground in that picture, only elements on the surface. I’m interested in the materiality of the canvas, which is why it is often left bare. There’s some text at the top, symbols, and collage stuck on. The collage is actually from these bird-life books I got from a charity shop. They have really lovely biological pictures of insects, stunning little pictures which found their way in. There’s one picture of a butterfly wing that I’ve cut apart, and drawn arrows in between, kind of drawing them back together. I’m interested in the idea of bringing together that which has come apart – rejoining, reconnecting, joining the dots again.

MC: That’s what I see in your work in terms of these really broad swathes of time, joining the dots between something so ancient that we have all but lost it, and something that is so contemporary and personal to you.

LW: It’s lovely to hear that that comes across. One question you asked me previously was about psychic automatism. Psychic automatism is a method of stopping your conscious mind, allowing deeper forces to bubble up from within us. I used to understand it as bubbling up from one’s own unconscious, but nowadays I believe it comes from something much deeper than that. It comes from a universal consciousness, what Jung referred to as the collective unconscious. The immaterial realm of thought and mind works in a very similar way to the material realm. If you go deep enough into yourself – this is what transcendental meditation teaches you – you get to this infinitesimal point in yourself, and you get to that same point in the material realm, the zero-point field in quantum physics, the ether, the akashic record, this library of all energetic information in the earth. This is where clairvoyants learn about past lives, people with particular skills and insights are able to take information back up into their conscious realm. The zero-point field, the ether, is where dark matter comes from.

I look back at paintings sometimes and think, Jesus, did I make that? It seems so alien. I’m not sure where some of it comes from. In recent times, I’ve started to think it comes from this point which goes deeper than me, myself, and definitely deeper than the material me – the English, British, white-skinned man. Far deeper than that. That’s how I understand psychic automatism now.

It’s a methodology which people immediately associate with modernism, but I do think it is far older than that. Through most human creative acts, I think, some degree of automatism is at hand. You ask about ritual – I think, again, we can speak about it in an academic way, and utilising it for artistic means. But we all know what ritual is. It is to allow a certain state of mind, which allows us to perform and be creatively as good as we can be. Psychic automatism works in a similar way.

MC: In my mind, I had a very basic view of what automatism was: that you create a machine to do the drawing for you, or you cut up a poem and see where it randomly falls, and that’s the work of art. Taking out your own hand as an artist.

LW: In that sense, it links to tarot cards. The absolutely rational mind would just laugh at tarot cards, but I think that the seeming chance and coincidence of automatism, tarot, free association, automatic writing – there is deep meaning in it. But it requires a level of openness and vulnerability that some are uncomfortable with.

MC: You’ve mentioned about this idea of rationalism, and I think that’s something that I’ve noticed in all of your works. Even in a formal way, they are balancing chaos and rationalism. You’re not taking away all that is rational – you’re exploring it in a deconstructive way. But there’s always an element of chance. To get back to your painting process in the studio, how much of it is informed by chance?

LW: It’s sort of an ordered chaos. There are glimmers of spontaneity and allowing chance to happen. The studio is almost this sacred space where anything is allowed, and the chance of me knocking a paint-pot with my foot and it falling onto the canvas has as much currency as if I drew something with my hand. Then it’s a process of going into those accidents – for instance, I draw a circle around a spill. For me, that is indicative of the way that humans go about the world. We try and create order in chaos. Science is about trying to give ourselves security and safety on what is an extremely dangerous environment for us evolved apes to exist within.

MC: Knowing that your work is pretty improvisational makes the considered choices that you make all the more interesting. The curved edges, the unstretched canvases, the way you display your work. It is very interesting.

LW: Thank you. First and foremost, I felt restricted by just painting on a wall – the idea that the work is simply a layer of paint. You’re not considering the thing it’s made of. I then started to work on the floor, still stretched, but I couldn’t get to the middle of the canvas because you couldn’t step on it. So I took it off the stretcher, started painting on it. And it completely opened up a whole new way of working where I could cover all angles. I’m also painting on the floor – in so much of my practice I’m focused on natural forces and being in-balance. A real strong belief in animism, an animistic balance that exist in the world. So painting on the floor is utilising the organic force of gravity – when you drop paint it falls to the floor, it doesn’t fall to the wall. Being able to be on top of it, on it and in it, painting from the inside out, allows for so much more potential.

I tried lots of different things when hanging the work, and eventually landed on the hooks. I love the way that they look like tapestries, or also connotations of hanging meat on a hook. And also skins. I had a show in 2022 called ‘Skin Crawl’ – the idea of things crawling under your skin or hanging skins on the wall – these paintings that are like membranes.

The curved edges came from hanging the work. When I unstretched a painting it creased at the edge, and I cut out the crease, and just happened to be with curved edges. It just looked so good with that picture. I played around with how big the curve would be. On the larger works, the rough size of these corners became a sort of uniform element. I’d done so much experimentation, I wanted to land on something that I could recreate.

In all of this, I was very aware of where I could situate within this seemingly abstract language – also being a man, being white and European, you immediately get unconsciously put into brackets of historical narratives. I wanted to release myself from that, to gain awareness that this is something other, pushing in a new direction. Also I wanted to push against what felt like dogma in painting – that this is the way you paint, this is how to do it.

MC: It’s so successful. The quote which I started this investigation with seems to sum up for me the effect of all of this on your work: ‘the paintings speak of a oneness…the image…pictorial ground and gesture become one…and, finally, the work of art is the ritual process.’ We’ve already talked about ritual, but you can definitely tell that there aren’t definitive layers – it’s not painting on a canvas, it’s in the canvas. You can see that by the way the pigment bleeds in. It’s all very unified. It doesn’t seem like a very deliberate act of just putting stuff on, like an image on a screen.

I wanted to ask you, to go back to the idea of music alongside your art, and whether the two interact – as a DJ and a producer, and a curator of sounds…

LW: I mean musically, running the label, I feel very much like a curator – curating records, track listings. My parents run a dance business, my mum’s a professional dancer and my dad ran the music side of things. I grew up with dance routines being choreographed at home, my mum judging competitions. So that had a profound effect on me and is one of the reasons why I DJ. From early on, it was the power of dance, which is a communion. I believe in the power of communion and collectivity – and in the society that I grew up in, there isn’t much of that. Neighbours don’t know each other anymore. That comes with sharing a dance floor with people and getting lost together.

To some extent, we all pursue ecstasy – whether that’s sexual ecstasy, dancing, musical ecstasy – we are all on that journey of attaining it. It’s also, moving towards visual language, about trying to distil these feelings of communal ecstasy on the dance floor, with sounds elements, vocals and speech. It’s everything on a dance floor in a picture. And as I’ve got older and started reading more, I’ve become more interested in frequency and the power of sound. One of the reasons why I wrote this essay and do these pictures is because I believe in the healing potential of music and dance. And pictures.

One thing you mentioned earlier was the problems with terms like primitivism and cultural appropriation, and also the fetishisation and exoticism of these ideas. If I had more scope in the essay I would have written about these critiques. Regardless, with all the Modernist artists I mentioned in that essay, there was something that I feel was heartfelt behind their engagement with shamanism. It wasn’t like Gaugin painting pictures of Tahitian women. It’s not pictures of shamans. It’s trying to engage with the shamanic spirit, and its ideas and methodology in this universal spiritual practice. I think what they were trying to do, as I ended the essay, was that the world that they experienced with world wars, famine and influenza – it was complete and utter destruction. They were trying to heal the world. They were trying to help, in some degree. In different ways, I find that the world I live in is as bad. As bad as ecological disaster and environmental collapse is, the real problem we face is greed and apathy and selfishness. The community aspect of sound, dance, frequency, and the sharing of artistry is, for me, a fundamentally healing force. The reason why I come to make is in hope of being of service in that sense.

I’m pretty certain I have synaesthesia – I see sounds. Individual sounds are referred to as colours, forms and shapes in my mind. But I also believe in the power of sound and frequency to affect our lives. 432Htz is known as the love or healing frequency. The science of sound affecting our body, this has a huge influence on my work. I believe in the potential for pictures to operate in the same way. So that a picture could have a healing aura about it. When developing this way of hanging work, I loved that they move and dance very slightly. It brings the reception or experience of a painting more down to earth, becoming more easily accessible. All these things, I hope lead to a more comfortable and potentially healing experience.

I’m not trying to say anything new, or mind-blowing, academic, intellectual or ironic in my work. It is honest – I try to be honest. It is trying to get down to the real nitty-gritty of what it means to be human, and what it means to exist in this strange world. Trying to find answers without feeling that it’s futile, questioning the world. The paintings are snapshots along this process.

MC: I think that’s a very noble goal! It’s very wonderful to hear you talk about your work in this way. Can we sum this up with three names of your contemporaries, who inspire you or have an accordance with your work?

LW: Sarah Cunningham. We’ve spoken about showing together at some point, because of the strong similarities. In her recent press release, she spoke about shamanic soul-flight because I had spoken with her about these ideas, and it had really struck a cord. Another one, Marissa Stoffer. We’ve had some amazing conversations about alchemy, cult knowledge and spirituality, frequencies and old alchemical ideas. And Archie Fooks-Smith. He was a year or two above me at Slade, and made this incredible degree show making material the DMT realm. His work is heavily influenced by similar ideas of the immaterial realm and altered states of consciousness and the strange, otherworldly nature of deeper realities.

Leave a comment