MC: So I would like to ask you first of all how you came to be here, how you started off as an artist? When did you first start calling yourself an artist?

RN: It was honestly about two years ago. I’ve always been making things, but painting was probably the beginning of my life as an artist. I haven’t been painting for that long, but once I developed a practice, I was painting every single day regardless of whatever jobs I had or experiences I was doing. It was through that discipline of applying that practice I felt that I was an artist.

MC: So it was good to have the RCA structure to force you into it?

RN: Totally. But the value of the course for me was the total lack of structure. It really is about the community that you’re in. I’d never been in a community of artists before. I studied art history and was just doing different things before, so it was a very intense and exciting chance. The studio was like a giant nest – it was wild, and chaotic, but amazing and an immediate introduction to what I think life as an artist is all about. Who you’re surrounded by, supported by, and kind of look to. Even moving back to have a studio in Hackney Wick where I was before the RCA, with people who are now dear friends and peers, feels like such a huge win.

MC: That’s so nice! I think that people assume that being an artist is very much like shutting yourself away in an ivory tower, but you show that it’s the opposite. Has studying art history fed into your practice at all?

RN: I think the biggest way that it has is the way I collect and research a lot. Not very directed research, but when I’m taking a break from being in the studio, I’m either recording or taking pictures or seeing shows. It all kind of comes into a scrapbook thing – scrapbooks upon scrapbooks. I used to do just collage and all these physical things, and its really is only in the last few months at the RCA that they came back into my practice. I realised, as it usually goes, that it’s all connected!

MC: So you were hoarding all this stuff and not really knowing why?

RN: Yeah. Being in this studio space is amazing, because at the RCA I had maybe a third of this space, with no windows or natural light and a really low ceiling. It was rough, but I really loved it. The only thing that was in there was this carpet, and everything was just sort of stacked up. The best way for me to work is to surround myself with eight hundred different things that I could pick from.

MC: It’s so nice – you’ve got a very cosy studio, with the carpet and lots of books and photos.

RN: I’ve basically taken all the books that I’ve had throughout my life, that would be in a bedroom or something, and brought them here, as a way of building out the space.

MC: I’ve spoken to some artists who feel like they resent studio time a bit, because it’s essentially just being inside a white box with your own thoughts. Whereas other people personalise the studio to such an extreme that it feels a bit of an intrusion to go in there, like going into their childhood bedroom or something.

RN: That’s kind of what I’m after. I want it to feel like a returning every time that I’m here. It also feels like a stage, like a movie set, because it’s all placed to imitate this home-space. But that’s exactly what I need to be somewhere where I can just work but also feel totally in my element.

MC: Let’s talk about the movie set thing. Because your work is very cinematic. And I see from that poster on the wall that you went to see Zineb Sedira’s ‘Dreams Have No Titles’…

RN: I saw her at the Venice Biennale two years ago. I went with my partner, and we went in maybe eight times. I was at this weird point where I was potentially going to go to Cairo and do a three-year Masters on the history of Islamic art and architecture, which would have been amazing. And I was sitting watching the film that Zineb Sedira made – this North African, British, American, French experience with all these influences – and I thought, I have to go to Egypt. A lot of these Arab and Egyptian motifs which show up in my work are mainly references to a childhood that my parents lived but I didn’t really get to live. My dad is Egyptian, but he emigrated to the US when he was 9 years old. So, it’s a very typical strange story of all these influences. But that exhibition took my breath away because it was the first time I felt this kind of very embodied experience, stepping into the artist’s world.

MC: It’s amazing – the thing that struck me about that work and about your work is that, to go back to the film set thing, it’s a construction of an idea of identity. Is that something that you felt? That you’re trying to create a construction, or version, of an identity?

RN: Yeah, it all feels, in the end, super connected to who I am. But honestly every work starts with a character who is some version of myself, and I build it out from there. Even the work in the degree show, the massive ‘JOCK’.

MC: Can you talk me through your degree show – the beginnings of that work and the way it turned out?

RN: Totally. There were eight works in the show, and all of them were made in the last three months so it was pretty fresh. I had a tutorial with Andrew Hart, and we were talking about the cinematic element of my work and what that means.

MC: Is that Andrew Pierre Hart, the painter? I love him.

RN: Yeah, he’s incredible. It was one of those experiences where I felt totally comfortable. The way that he works is very multimedia, very multidisciplinary and super open. I feel like my work really needed those eyes. We were talking through the idea of all these works in my show being super distinct, but all part of this invented narrative. We really played around with placement. You can take a really pared-back approach with exhibiting certain paintings that I’ve made, but through talking to him I realised that that’s not my language. We talked about this tessellating install which I ended up using. That was a turning point for me – obviously there are limitations with the space and sharing a room with four other artists, but in the end I felt really lucky.

The centre of that work was a full textile piece with the word ‘JOCK. I have a painting of the exact same size of the ‘jock’ character, which is just a self-portrait. It’s kind of a headless figure. It was only a few days before the show that I sewed that piece. I wanted a varsity feel, but super fragmented. I’m always worries about how fabric and paint work together. I’ve had to really emphasise how distinct they are, because if I try to put them in the same language on the same plane, it just doesn’t look right.

MC: You’re also working with some quite inhospitable fabrics like velvet and lace. It’s interesting to see how you combine the two, because they seem like two worlds away.

RN: I feel like what has worked for me is that I have to be super slapdash. If it’s too considered or thought out, it just doesn’t work. That gave me the confidence in the show to decide on that as the centre that I wanted, all fabric, and everything else is either just a painting or velvet on canvas – except for the top one, the eye, which is a photo printed on linen. That show ended up being a character portrait of the jock.

MC: Could you tell me more about the jock, where that comes from?

RN: I rowed for thirteen years, and forever I was like, I can’t paint or sew or anything because I’m training thirty-five hours a week. This is my life. I think that’s where my obsession with parts of American culture come from – the experience of being a student athlete on a division-one team, and how that totally shaped who I am but also directly blocked me from becoming an artist during my undergrad programme. I feel like it’s this kind of late reckoning with how central those experiences were, and how forever it felt completely separate to my creative persona or my experience being an Arab. It went very specifically with this very English-American idea of elite athletics and that whole sham. But at the same time, I feel like it’s resettling into a reckoning with what it was that gave me the strength and determination to do that for half of my life. So, it’s kind of a simplified self-portrait, but for me it has opened up little worlds or pockets of all the other vague identities that I kind of aligned myself with. It has to be very rough-handed, putting it all together. Having that one word that is so simplified works super well for me, because it then feels like almost a distraction and all these strange little paintings can have their own time or space.

MC: Are you playing with stereotypes, then, using the word ‘jock’?

RN: Definitely. Being called a jock is like – my dream. I love it, I live for it. It’s this super queer, hyper-masculine title and character that you associate with some man. It’s this word that I feel so giddy about when it’s used to describe me in a way.

MC: I feel like stereotypes are an important part of forming your identity for real – you really play around in them. You mentioned that every painting that you do is a self-portrait – you in a different version of yourself. Do you think you are trying to get close to some kind of truth? Or are you happy working in this playful realm, putting on temporary characters?

RN: I’ve got a lot of questions but I’m not looking for any resolution. I think there’s so much in a stereotype, so much that is either something to really aspire to or to completely reject. There’s a strange line there that I really enjoy. Even with the Zineb Sedira show, restaging all these important moments from film, good or bad, but also placing yourself in the scene and the narrative is such a strength.

MC: It reminds me very much of Michelle Williams Gamaker’s work – these constructions of Bollywood films, but where you can really tell it’s a construction. You can see behind the scenes, the cameras, the things holding up the set. I really like that as a very honest deconstruction without being too on the nose.

RN: I feel like a lot of the work I’m doing at the moment is so on the nose, as I’m still playing around with it – not that it has to be particularly nuanced.

MC: Your work takes the format of snapshots, screengrabs maybe. How do you find your references?

RN: They’re all from photographs I’ve taken. I’ll bring about ten or fifteen photographs into the studio every week, keeping everything around. I’ll go through them all like a book and pick an image that I resonate with at that moment, crop it, and then go from there. So this is a picture of my sister, and this is a distorted version of the Ugly Duchess’s hand at the National Gallery. Her hands are beautiful and so strange, it’s an insane painting. Obviously the reference comes from the painting, but it’s specifically about taking this crappy iPhone picture of this detail and then blowing it up. A lot of them are from pictures I’ve taken, but there’s also a lot of pictures from my grandmothers on both sides of the family. That one is of her car in the 70s.

MC: I love how you’ve narrativized it – looking at that, it looks like a still from an 80s film.

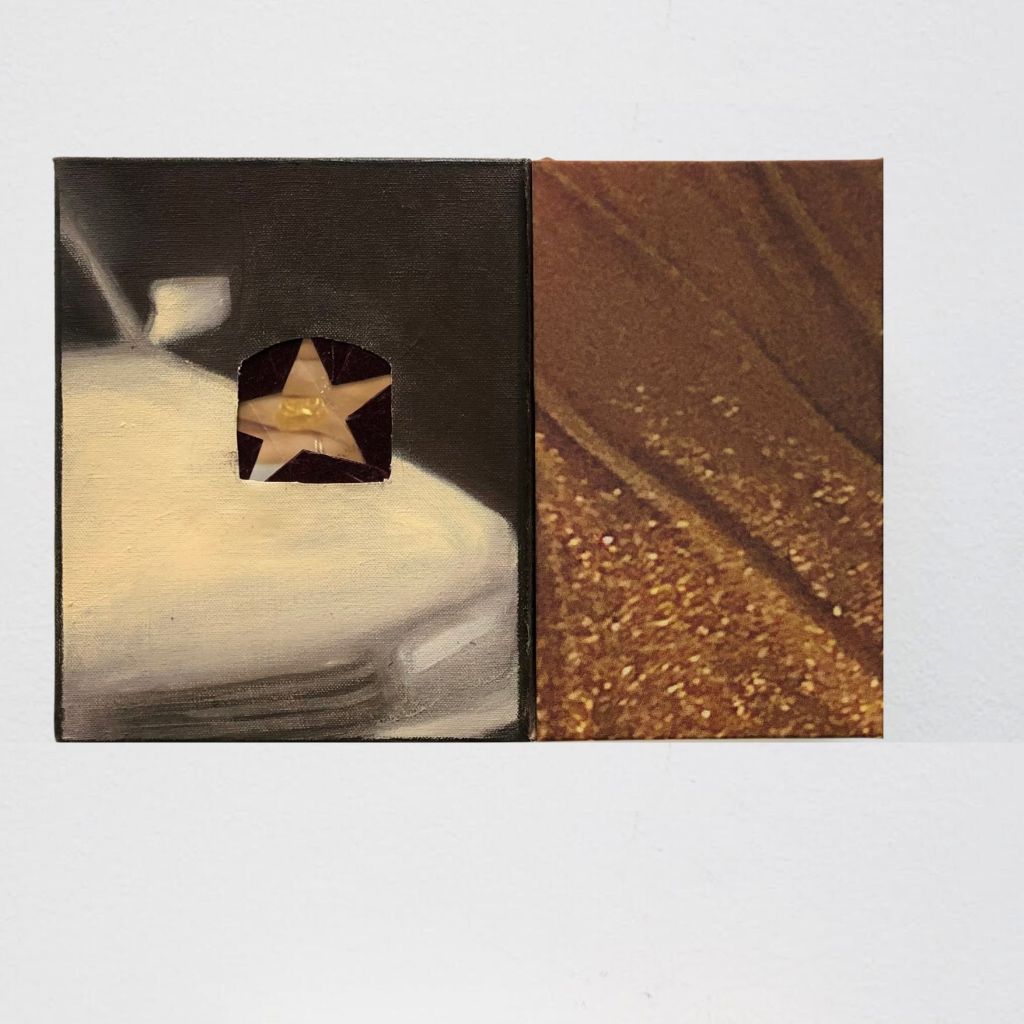

NR: And the star behind it – that velvet is from the same fez which is in that portrait in the degree show. It’s in the picture that I took that I then painted. I then took the fez apart. That one on the wall over there is the top bit. Inside the star I put the side of this bench near the capital building in Austin, Texas, where I sent a lot of time this year. I was just sitting on this bench. It’s kind of the perfect frame for this broken fez, and then behind that is my hand. So the work goes paper, velvet, and then painting.

MC: And there’s four layers of imagery there. I want to ask you more about your personal archive, and about legacy – what does legacy mean to you? You’re using a lot of stuff from your grandparents, your family. Do you have a lot of stuff?

RN: I do have a lot of stuff and I spent a lot of time… my grandmother passed away this year, and she was someone I was so close to. She lived in Texas, so I spent a lot of time there this year helping out and taking care of her in her last few weeks. Having the chance to go through albums. My grandfather is a tailor – all the fabrics he brought home, all the jackets, what it means to bring these objects, clothes and jewellery, out of her space and back here. Some of it ends up in the studio but feels not precious enough or something that I feel comfortable deconstructing.

MC: Yeah, I was going to ask you how it felt deconstructing the fez?

RN: It was a little bit scary. It was a pretty cheap, crappy one, but a meaningful one. It felt super sacrilegious or something. I used it for lots of different things and hopefully one thing will work out. But it felt super strange.

MC: In a way it’s nice to not be too precious about these things.

RN: Totally. Sometimes people will come to my studio and see the state of some of my books, and I’ll be like – I love them, and I return to them. So none of them are pristine. Even with a lot of my paintings, moving into this studio. A lot of works have been damaged in little ways and then it works itself into the composition – I figure it out.

MC: In the same way it’s like you’re not too precious about identity – not being precious about these things that are a part of your identity.

RN: My bedroom at home is so organised – I have this tiny cabinet of tiny glasses, and this amazing tiny frame. I find these things so beautiful. That’s the way I care in that space. But it would do it a disservice to be like that here in the studio.

MC: And how do you feel about the idea of legacy? Do you feel like your collection is like an archive you’re eventually going to pass on?

RN: Yeah, I keep everything. Once something feels ready for me to cut it up and use it in all these things, it feels like… well, if I use something once, I’ll use it again and again. So everything has a place. That’s the problem with having bags and bags of fabric scraps and old magazines and pictures, it can be super overwhelming and hard to sift through. But at the same time, it feels so comforting. It does feel like I’m building something up.

MC: The fact that you’re using and changing these objects to put into your work – have you ever considered putting them into an installation? Where do you see your work going using these objects? Because of course, cutting up these objects in works is unsustainable because eventually you will run out of things.

RN: I feel like I have this idea of a living room set where everything is a reconstruction of an object I have – like for example, the tiny little cabinet. I want to rebuild that in some other way. When I was printing all these images on fabric, I kept just reupholstering everything in my room with these images of like, my great-great-uncle’s hands and stuff. It was super strange. It feels like in the years to come there will be something along those lines.

MC: To recreate things, to create multiple iterations of the thing, but not to lose the sense of the thing. That is very interesting as an artistic approach. It forces you to be creative in your methods and mediums, if you’re having to recreate something that even you might lose or break at some point. Trying to maintain it’s aura, in a way. I love the idea of the living room – kind of hyper-domestic.

RN: There was this ashtray that I really wanted to put into the degree show, but then it became super clear regarding the value of bringing in this super-legible object into a collection of those paintings I wanted to show – it was so distracting.

MC: It would detract from the work you are doing with your use of medium. Yours is a very process-based work – there’s so many mediums being combined; it’s layered and complex.

RN: Lots of trial and error. What I’m really excited to do is to push the object experience of the work. For the degree show, my practice really solidified, in a way that is deeply rooted in the fact that I am not seeking these bodies of work that feel related. Every iteration of something takes me somewhere. I was so anxious to not have these things feel super coherent and related. I couldn’t stop thinking about that. I’m excited to push the expansion of the work through the objects that inform it. The tiniest objects are heavy with stuff. I can’t let go of things, because it feels like it means something or will serve some sort of purpose.

MC: Being a nostalgic person – it’s a great thing!

RN: I feel like there’s such an emphasis on streamlined, clean living – but I feel like I will never be that. Maximalism is the core to who I am!

MC: This leads me to ask you what the challenges and benefits are of being an artist in London today – especially an artist with so much stuff!

RN: I am currently looking for a job for the next year. I was super lucky to be supported through the course and to be able to fully dive into this space and have the time and space to consider how this could be a feasible career. So, at this stage I still feel like a toddler, but the people I’m living with and share a studio with and who I see every day – they’re all people I’ve met through the RCA. I think the experience of being at the RCA has, more than any education, made it feel possible to be an artist in London right now. But I still have no idea. I worked at a gallery in New York, and I was teaching for a while. But you have to be able to paint two days a week, and working at the gallery did not allow that. It was an active block to making. So when I came back to London after five years away, I reverted back into my twelve year old self. Being at the RCA would not have been possible without that family support, but everything leading up to that point and, fingers crossed, going forward, was like some kind of dance.

The athleticism of painting is so core to my practice. I loved rowing and I loved feeling like this machine. I think the love for that feeling is the determination that, whatever else I have to do to make it work, I will be here doing this. Love of that discipline is what opened up my work.

MC: My last question is to ask for three names of people who have some accordance with your work, who you would recommend, or who inspire you.

RN: The first one is Sa’ad Choeb. He was on the RCA course, he’s a Syrian artist and an incredible person. The way he works and talks is incredibly inspiring to me. I think also Jonathan Tignor. He’s from Texas, and my best friend, and he’s just an incredible artist and rigorous worker. The way that he approaches narrative in his painting I find so compelling. I feel like he’s constantly searching for something, and his work doesn’t hold itself back – it’s all super experimental. Working alongside him this last year has been super impactful for me. Finally, there’s these two artists who work in a duo – Athen Kardashian and Nina Durban. Of all the work I’ve seen, I’d say that they’re influencing me the most. The way they build these composite images and themes. I’m just obsessed. Looking at work like this gives me the confidence to push what I’m doing, and it helps me to think of the personal as super important and strange.

MC: That choice makes so much sense. Thank you so much!

Leave a comment