MC: What’s your journey? When did you start to call yourself an artist?

VL: So the earliest memory I can remember was in primary school, when I had English lessons and the teacher would say, to accompany this book that we’re learning, draw a picture. I remember focusing so hard on the drawing and not focussing on anything else. Then my teacher told my parents, hey, your daughter can actually kind of draw. At that time I was watching a lot of painting stuff on YouTube – painting tutorials, time lapse. I was super fascinated. In Singapore there’s this place which is part painting-place, part café. They give you a canvas and a reference photo and acrylic paint, and you can sit and paint for three hours. So that was my first introduction to painting, when I was about nine. I would go every Saturday to paint.

I went to an art high school, and that was where I took it a bit more seriously. The after I graduated I took a gap year, and I focussed completely into painting. I developed a bit of a style at that time. And I think Covid was when I was just thinking about art twenty-four-seven.

MC: Were you going to see a lot of other artist’s work, and did that inform you?

VL: I was actually looking a lot online. I was looking around me as well, but the things around me didn’t interest me that much. So the stuff online, that really influenced me a lot – a bit too much, at the time! I think I’m still trying to grapple with the word artist. I prefer the word painter.

MC: Looking back through your work, I can see a change in your style from your older stuff to now, especially with the figures. This is conjecture on my part, but maybe you are looking more at the idea of beauty in your older work. You’re painting these plasticky, alien-looking figures in groups, almost like models. There’s a kind of emptiness to it. But now, it feels more about the body itself, about the gaze. Dealing with power dynamics in that way. I was wondering if you could explain the change in your thinking?

VL: I think definitely moving to London. The change in my environment, and seeing the paintings surrounding me and what inspires me. I think I just got bored of what I was painting, and I felt like I couldn’t relate to it anymore. I remember at one point, when I was still painting that alien stuff and people would interview me about it, I felt like I had a script. They would say, like, I heard you’re really inspired by sci-fi, and I would say yes, but when I was seventeen! I honestly just don’t relate to that style anymore.

I would say that I am really focused on the gaze and power right now, but it is a constant thread running through my entire practice – I just brought it forward. There was a painting I did called ‘I am Mine, in Your World’. And looking back I’m like, wow. I thought then what I am thinking right now. But I kind of stopped it then and I am only now going back to it, adding more to it.

MC: So the idea of the gaze is very interesting. In the history of art it is thought of in relation to the first paintings where a woman is being depicted, usually nude, looking back into the eyes of the viewer. Returning the gaze. It is thought about as a very empowering thing. Do you see it that way?

VL: No, I think I see it as a more complex thing. I don’t like when things are segregated into the male and female gaze. Because I think that a woman can be playing into the male gaze, but that can be feminist also. It is very binary to say that this is the female gaze, and this is the male.

MC: Yeah, the words have lost all meaning, in a way. The idea of the male gaze denies the existence of the female gaze. The point is that the woman is always under the male gaze, whether she wants to be or not. It’s all-encompassing.

VL: Exactly! I feel like there’s so much labelling with women’s bodies, either way. Like, who is she doing it for? Is she doing it for herself? Is she not doing it for herself? There’s too much judgement which plays into what we’re doing. So I think my paintings are an exploration of that. These women, existing, with no judgement. But then at the same time, I really like the idea of concealment and exposure. What they choose to conceal and expose. The question is if they want to conceal it or not. That’s for the audience to decide.

MC: There’s a wonderful painting of yours called ‘Happy Baby’. To describe it, it’s a woman lying down, nude, with her legs spread apart but facing away from us. There are two other women looking at her, but she’s looking back at us, over her shoulder. We don’t see anything. And that’s interesting, because she is comfortable in the company of these other women. And everyone’s naked, as they are in all of your paintings. But the audience are not privy to her nakedness, even though she’s obviously decided that the other women are allowed to see her. She’s got this cheeky smile as she’s looking at us – like, I know what I’m doing!

VL: Exactly. That painting was inspired by TikTok actually. For some reason, my feed at that time was full of people doing yoga. There was this particular instructor who very clearly wanted that kind of attention. And I thought, ok, who has the power here? Is it the people in the comments? Is it her? Is it the audience? So I explored that in that painting.

MC: I love it. Another thing that you use a lot in your work is distortion, through mirrors and steamy glass, and also just through the way you paint. You are also focusing on the parts of the body that often people find ugly – double chins, rolls of fat, stubble or feet. Could you talk a little more about that? Do you see that as an empowering thing?

VL: Yeah, I think it’s always fun to paint this kind of stuff and make it the focus. You’re right on with the mirrors. I’m really exploring that now, actually. Reflections, water. You know when you’re walking and you suddenly see your reflection and you’re like, woah! I look like that! It’s a confrontation with yourself. I’m always intrigued by the shower, because I think it is a place of very extreme intimacy with yourself. Seeing your body distorted by the metal reflections… it’s very interesting to me. It’s part of the gaze as well – in a way, a self-gaze. I really like painting hands and feet. I think they’re a good indicator of a body. A good enough indicator to play with everything else in the anatomy.

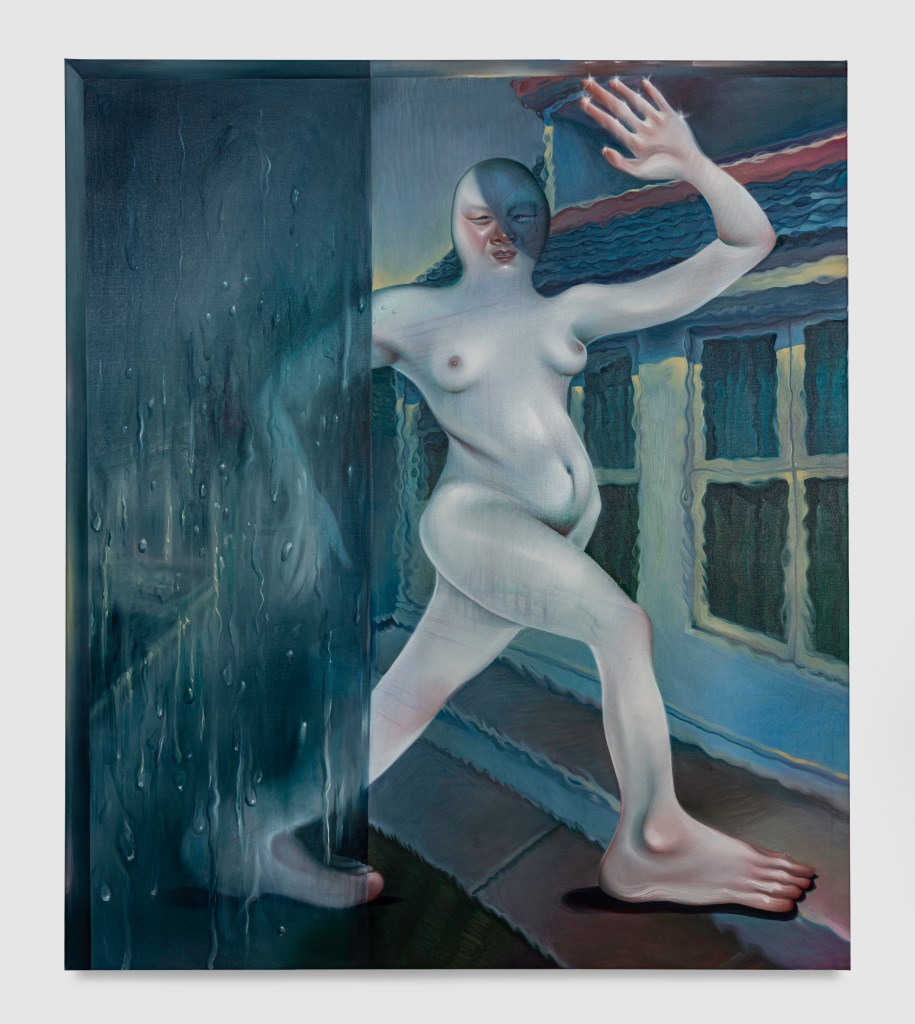

MC: I really like the work that you had in the Guts Gallery exhibition, ‘Softer, Softest’. That was a very interesting work. The figure is, I think, coming out of the shower, and there’s a sort of screen of water on one side. And they’re naked and moving across into the open space. And they look like they’ve been caught unawares. There’s a lot of shadows and veils going on. Could you talk me through the original impulse to create that work, how it came about?

VL: That work was inspired when I was in Singapore. It was during last December through to February. I was anxious during that period of time, I think, about a lot of things. I felt compelled to talk about it. So the background of that scene, the buildings, are actually my neighbours. Whenever I feel sad I always look out onto my neighbour’s house. The title of the work is ‘From Blue to Yellow, From Yellow to Pink’, because when the sun rises and sets, the colours of the neighbour’s wall would change. I found that really comforting, so I wanted to base my painting on that. And you know how Singapore is so hot and humid? It was extremely sunny, and one minute it would rain heavily and the next it would be so hot. I felt disconnected with my surroundings. It was very disorienting. I was feeling all sorts of ways, but I would look out and it would be so bright. I wanted to capture the moment when the sun is slowly coming up after it stops raining. This was sort of my entry-way into the idea of concealment and exposure. She’s white, she’s blank – she sort of wants to hide but she’s forced to be exposed. I really like that conflict.

MC: What you were saying about feeling disconnected and dissociating – there’s a weird double feeling I get when I look at your paintings. I feel both super embodied, because the bodies are so clearly and realistically painted. Moments of recognition, of the universal experience of just existing in a body. But then also they’re so alien and distorted, it does feel like a trigger for dissociation, in a way. Like when you look down and your hands are too big. Why did you decide to paint them in this alien way? You’ve mentioned sci-fi before…

VL: It was always an interest to me. Definitely before, it was a much more explicit things – they’re aliens, bald, wide-eyes. But now it’s becoming more of a self-portrait, more and more realistic. But I can never paint hair, all my characters are completely hairless. I didn’t want a character that was so easily digestible, I guess. But I think that this feeling of disconnectedness has always been around, like the gaze. There are just levels to it. But this specific painting was a bit of a separate thing. It’s a very emotional piece – I really looked inward instead of looking out.

MC: It worked very well in that exhibition, especially with this idea of the veil being a double-sided thing – sometimes it’s a softening, like looking through a misty veil of memory or nostalgia or rose-tinted glasses. But it’s also a thing you hide behind. You use the idea of the veil a lot, like with the steamed up glass.

VL: I really like indicators like that. Being both there and not there, concealed and exposed.

MC: I would like to ask you more about your studio practice. How does it work, from start to finish, when you’re making a painting? Are you a big sketcher?

VL: Actually no. I scribble a lot, and I have thumbnails, but I never sketch anything out or shade it in.

MC: Even the colours? Because the colours in your paintings are very specific, and because they’re artificial maybe more difficult? You can’t be observing them in life-drawing, for example!

VL: It really depends on my previous work. Sometimes I’ll want something similar, and other times I’ll want something completely different. ‘Happy Baby’ was really colourful, and then I was quite sick of that purple colour, so I moved on to white and yellow with the work in Guts Gallery. I thought white was a really interesting colour, to see how I could work with it and what I could create. Typically I have an idea in mind. I need the canvas in front of me, and then it’s just a lot of staring. Staring, staring, drawing, and staring. Then I will take some photos, and to get a clearer picture I might do some photoshopping.

MC: I also would like to ask you – what has been the main difference for you as an artist between Singapore and London?

VL: I mean, Singapore is way smaller and much more dense. Everybody knows everybody. It’s definitely easier to get noticed in Singapore, because not a lot of people are doing painting. It’s comfortable here. But in London – the shows I’ve been to, in a weird and good way, are kind of discouraging because… woah! You really get to see what’s outside and the possibilities of how paint can be manipulated. It’s discouraging and encouraging. Seeing how the medium I’m working with can achieve this. One of the only reasons I would ever consider living in London is because of the shows there.

MC: It’s been interesting talking to painters in London because there’s a certain generation who are really aware that, for a period up until maybe the mid-2000s, painting was so uncool! And now painting seems to be back and selling well, but in a way that galleries sort of use it as a get-rich-quick card. Especially abstract. I think painting is in a weird place, but I’m excited to see where it goes.

VL: I know that uncool thing – I’ve been there. I’ve always had this insecurity, especially in school, because the people were doing installations, performance, and I was just painting. That’s why I hesitate to call myself and artist – it’s always a painter, for me. It feels right.

MC: So, my final question is to ask you to give me three names of contemporaries of yours, or anyone whose work has an accordance with or influence on yours.

VL: There’s so many! Number one is Danica Lundy for sure. Oh my god, her solo show at White Cube blew my mind. Normally I don’t go to White Cube, but somehow I stumbled on this. And I remember being there for like two hours. Her work is just so dramatic. Like – how did she think of this? It’s so poignant and powerful that you don’t need text or anything – you can just go in and feel it. I love paintings like that. The things she paints are really mundane, but she manages to make them… insane.

Next is Li Hei Di. They’re based London I think, I went to their solo show at Pipi Holdsworth. Their work is abstract from afar, but when you look closer there’s a lot of anatomy hidden inside. Again, it brings me back to the gaze. Their way of explaining is that they treat this abstraction as a sort of protection for their subjects – treating them with care. I really like that. Technically, everything connects but disconnects, and I don’t know where to look first.

My third one – I really like Timothy Lai. He’s a Malaysian painter. His compositions are really interesting. I love paintings which play with the relationship between the audience and the painter. Like, am I supposed to be here? It makes you think about what is going on outside the edge of the painting. The rain in my painting at Guts Gallery was inspired by his work – his technical skill in painting rain.

MC: All of your choices have such a clear link to your own work. Thank you so much!

Leave a comment