MC: Could we start with you talking me through your exhibition which is opening in Fitzrovia gallery soon? What is the format going to be – live performance?

LL: Not this time, unfortunately, because I don’t have the time and energy for it. I have the gallery for a week, really only five days. For the private view, I thought I would do a whole plethora of food where people could come in and take whatever they want to eat. Everything’s going to be home-cooked as well, so I would need to have to come up with an allergens list. Other than that, it’s free and easy. I’m including my ‘Retirement Manifesto’. That’s the first thing you’re going to see when you enter the door. Along the two sides of the corridor is going to be the ‘I love my country’ work, and then the other side is going to be a whole row of recipes that have been done before and printed out. The food is going to be placed where the gallerist usually sits, in the corner. And there’s going to be an old work of mine, ‘I love you too’, with the old relics of broken plates that are swept under the table.

MC: I was going to ask you about that work, ‘I love you’ and ‘I love you too’. Could you talk me through it?

LL: That one came about in the first year of uni, actually, at the end of Foundation. That was the work which brought me into performance art as well. Initially, I was planning on doing a video of the thing, and my tutor was like, why don’t you try to do it as a performance? And I thought no way, I’m going to freak out in front of people. But then I tried it, and it ended up going well. Maybe it’s one way of more directly impacting the audience. Also, typically, the type of performance art I was exposed to was more about body movements – at least back then. It was more about artists exploring their relationship with their own bodies, and their own minds. But that’s not me – my hand-eye coordination is simply not up for it. I explore the language side more, I’d say.

When that work was happening, it was my first year out of my family home. My family is based in Singapore and I moved out for uni, out of the whole toxic environment. So you start looking back, reflecting on your relationship with your parents and your mum because you’re outside in a third environment – looking from outside looking in. It gives you a clearer perspective on everything, not just your family but politics too because you’re not in it. You don’t get involved or engaged with it, so you can see it clearer; and you can see how tough love is and what kind of effects this can create for children.

MC: And how did you translate that into the piece? Could you describe what is going on in that performance?

LL: For that performance, I wrote eighteen lines, because I created that work when I was eighteen. An independent age is when you move out and start doing things on your own – at least, you think you’re being an adult, about that age. So I picked eighteen lines, things which my family would say to me. These things, I didn’t find them problematic when I was a child, but afterwards, when I got to my teenage years, I started to see all the gaslighting and all the rest of it. I wrote each line on a plate, and they were laid out on a long table. I then bring in a bunch of flowers, daffodils – because daffodils symbolise new beginnings, spring. Also, we don’t have daffodils so much in Singapore, it’s more in the UK that you see them. I would read the lines, and then smash the plates. You break the plate, and you break the ties or your relationship with the lines, and the control they have on you, the toxic side of the family bonds. You would want to release it; you don’t want it anymore. So on a personal level, it’s very cathartic.

One of the reasons why performance art is so interesting is that you can’t control every single element. You can control your stage, and what you do, and you have rules to everything. But I like to leave out one or two elements to “fate”– like in a science experiment, you leave the hypothesis that you want to find out empty, and the plates breaking bit is the element for this work. Based on the sounds of the documentation, you can tell some of the plates didn’t break during the performance and which ones didn’t break. The ones that don’t make a much rounder and echoing sound, instead of a clear clash. The echo was really really torturous, at least to me. There’s almost a tension there.

Based on the fact that some of the plates didn’t break, I felt that that was a sign that the story does not end there – that there should been an ‘I love you too’ performance. ‘I love you too’ is more about my reaction to that of ‘I love you’; that the plates didn’t break, and you can never forget and never deny that the past has happened. In reality, after the happening of ‘I love you’, I had a conversation with my mum, and during the conversation, it felt like it went well. However, straight afterwards, everything went back to normal. And so, at the end of ‘I love you too’, I swept all the broken plates on the floor under the table, almost insinuating that everything is covered up, but the broken pieces are still there. You can clean the mess up, but you can never deny that what is broken is still there. You can forgive it, and you can learn from it, but would you be able to forget it?

MC: It’s fascinating, you have this personal epiphany through this chance moment. It’s the epitome of what performance is about, right? I was reading your bio on your website, and you talked about how your experience of growing up as a second-generation Singaporean in the UK led to you doing performance art – putting your own body in the work and placing your own experiences front and centre. I was wondering if you could talk about that a bit more, with some examples. Of course, ‘I love you’ and ‘I love you too’ are good examples, but they’re located only within the family home.

LL: Even within the family home, it’s still true. I initially didn’t draw the line between second-generation immigrants and not, but afterwards, when you start learning about other people’s stories it kind of links up. For instance, how a lot of kids whose parents migrated and they were born there – a lot of what they do for the family in terms of translating legal documents etc, hits home. The parents are not going to be that well-versed in the English language, but when it comes to legal documents and stuff like that, the kid has to step up and translate it. In all gratefulness, we were given that life, that better environment, to experience something different and new and great. The pros come with the cons, the responsibility to step up when you are still a child when you are technically not supposed to step up. Your only job of being a child is to be a child, but a lot of us didn’t have that.

My parents’ tough love situation was quite similar. In my conversation with my mum, she commented that she did not realise she was putting that much pressure on me. I believe she wasn’t particularly engaged in the culture whilst we grew up, and she didn’t have a group of Singaporean friends, people who she could bond with language-wise or food-wise. Because she did not know the environment well enough, she remained a third person in that environment. So, her mentality is going to be as it was where she had been raised – and it’s not the same education system that you would receive in Singapore. However, I do not believe that it is out of any bad intention that she brought me up in that particular way. It simply reflected on her upbringing or insecurities rather than that of my “lack of future”.

This is why, the more recent work ‘This is Illegal in Singapore’, part of it was inspired to explore the idea of intergenerational trauma. In the initial stages, I wanted to explore the intergenerational traumas of East Asian families, or more specifically women, i.e. the relationships between and amongst daughters, mothers and grandmothers. I didn’t follow that through because I want men and everyone outside of the East Asian community to be part of this conversation as well.

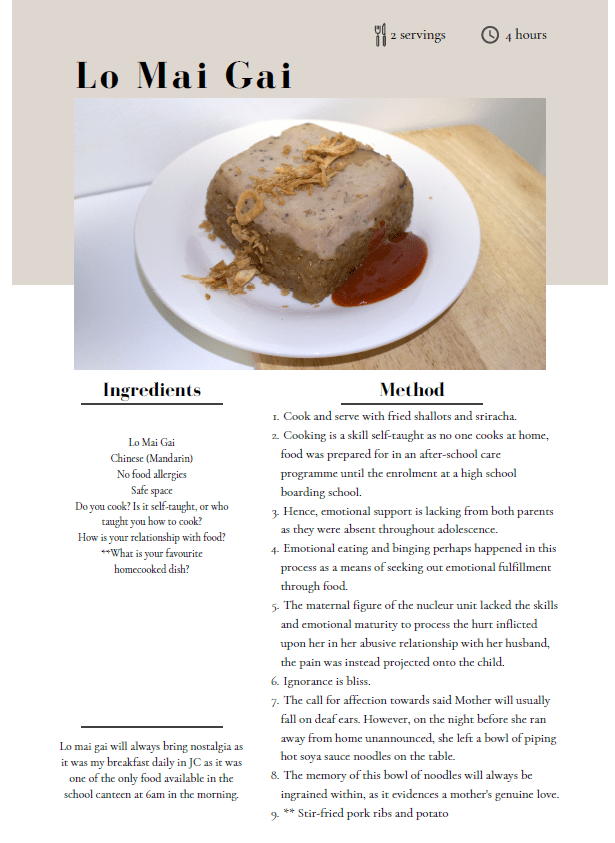

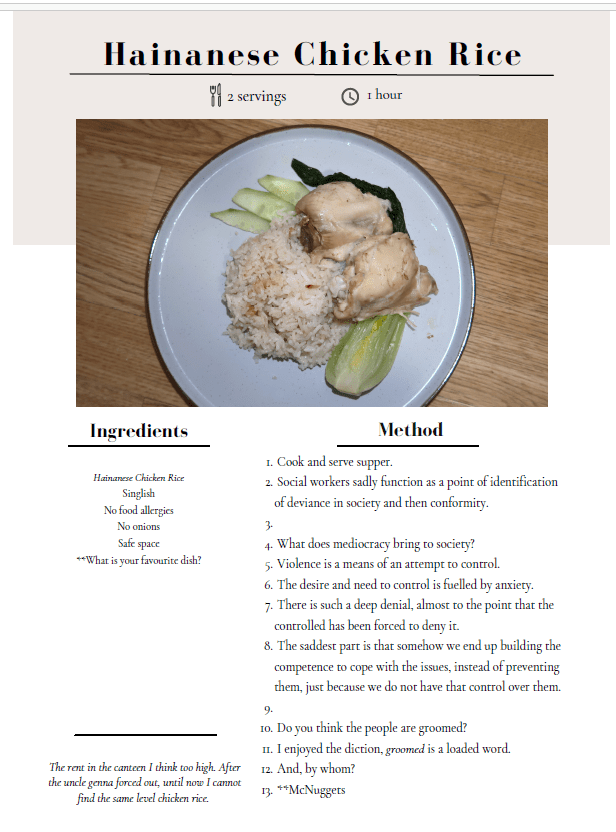

Up till now, I had only been cooking specifically Singaporean food, and I thought that would be interesting because I didn’t grow up eating Singaporean food. It’s not my comfort food – mine would be Northern Chinese food, like hand-pulled noodles, doughs, and meaty dinners. I just thought that using a Singaporean dish could tie other people together, very much like the Singaporean culture, the cuisine is very much alterations of various immigrated cultures, from all walks of life. In front of someone new – a stranger, someone who has come in for the performance – I’m going to be the most ignorant person. I know nothing about them, and I am here to learn, to provide an as safe as possible space to talk about anything they want to talk about. Their identity will be concealed, their name will be concealed. The only thing that could identify them is their choice of their favourite dish or the dish that represents them. This is why I say that, as a person, you embody your own experience. You can’t embody anyone else’s. Even if you pretend, you have a reason why you’re pretending, a goal that you’re trying to achieve that is still part of you. I thought that was interesting, that’s the thing that drew me into performance in the first place.

MC: Why did you give it the title ‘This is Illegal in Singapore’?

LL: I was initially going to do another show in Singapore last year, which is why I went back to Singapore in April. I was talking to an artist discussing the idea of doing a solo show, with my previous work. In the show, I was going to explore the idea of relationship between patriotism and nationalism. The plans, however, went down the drain due to venue issues. Exhibition texts, wall texts, lists of works had all gone through – it was just the last bit when I asked to set a date when it couldn’t go ahead.

One of the works in it that I wanted to do – it wasn’t a work initially, it was the idea that I wanted to provide food and share the love for people to come in and just help themselves. You know how some bakeries, at the end of the day, start selling their bread really cheaply, for a dollar per bread? Or some would collect all the leftover bread and gift it to charity or the homeless or low income. Before my show, I was talking about my idea or concept to the gallerist. Due to the London-Singapore time difference, it was the middle of the night for them, maybe 3 or 4am, and there were a lot of migrant workers just lying around on the streets sleeping on the floor. I had never been in the city on the roads past 11pm because of my parents’ very strict curfews. My gallerist was walking along Marina Bay Sands and there were all these people sleeping. They were either workers that probably didn’t make it back to their dorms in time, or they’re homeless. It was just a juxtaposition in such a wealthy pristine area. But you would never, ever see that in the daylight in Singapore. The common consensus is that there is no homelessness in Singapore.

MC: Yes, that was what I thought was the case, because of the state-funded housing system.

LL: Exactly, but there are flaws in it. It’s not about what you see, but what you don’t see. Everything is under the carpet, everything is under the table. If anything happens, it’s going to be hidden. Which is why I thought ‘I love you too’ was interesting, with sweeping the broken plates under the table, because it’s still true! It started with my own family and personal experiences, but when you step back and view it in the bigger picture, at the society level, there is a parallelism there.

Initially I was going to give out the food to the homeless people. At least, if they’re hungry they can feel free to grab it. Kind of pulling into the little gap between the idea of what is art and what is not, using food. But then my gallerist just said, “you know that this is illegal, to bring food out to the public.” He explained that it’s alright if the food has expiry dates (i.e. canned food, or licensed restaurants), but mine is home-cooked and you can’t give out home-cooked food. I do understand that it is also in cases when people have allergies and it was unbeknownst to me– if anything goes wrong they can just turn round and sue you for it. I do understand that rules applies to protecting people, but I couldn’t exactly wrap my head around that initially as there are so many homebased bakeries or businesses. Essentially it is alright to sell, but not to do it out of goodwill? Which is why, when I eventually did ‘This is Illegal in Singapore’, I did it in my own home. I decided to bring people into my home instead of bringing the food out to them.

MC: To describe the way you did the performance – it’s a small space with a table behind a curtain. Was that in your own home?

LL: That was actually documented for my degree show, and it’s in the Royal College of Arts’ studio space. I got my own dining table set and brought it in. I cooked food at home and brought it in half-prepped, and then I finished it in the pantry area in the studio. People would sign up online, and then come in freely. I would ask them for their allergies and dietary restrictions, and then they could just come in and chit-chat. All the food was Singaporean, and I would choose the dish based on their preference. I would ask them for their preferred name, dietary restrictions, dietary preferences, and their favourite dish, and your identity is only going to be viewed based on your favourite dish.

Some encounters were really interesting. Based on their favourite dish and experiences, you could kind of socially-profile them. And some people actually came back to do it twice, mainly friends. We would wait maybe half a year, and they would come back and their chosen food would have changed.

MC: It’s very interesting to see people’s different reactions. But also – you mentioned that language was the thing you are most interested in when it comes to performance. And what you mentioned about your family, and the different schooling expectations between China and Singapore – this strikes me as an issue of translation. I was wondering if you could talk a bit more about language and translation in relation to your work. How does translation and the spoken word come into your practice?

LL: I think for me, it’s more about the creoles and the accents, and about how these accents come about and play with one another. Not so much about translation, although I do think there are some nuances between languages which are untranslatable, I do hope to explore those during the performance and in my practice in general. I switch between two languages and potentially different accents. I do speak Mandarin, but when I speak Mandarin, my accent is not stable or fixed, nor a reflection of where I come from. My family is based in the north side of China, so I have a Northern accent as well. I end up code-switching both in Mandarin and English. It is very mish-mashed.

Singaporeans don’t speak in English-accented-English, they speak in Singlish — lots of lah, leh and lorh at the end of sentences, and with great efficiency. It has the English words but with the Chinese grammatical syntax. For example, in English it would be ‘Have you eaten’, putting it in Mandarin syntax would become ‘You eaten already’, and that’s Singlish. When you’re travelling as a Singaporean, and you hear a Singlish structure float by in the environment, your ears are going to prick up. I know you! And if you’re overseas studying, and you have no sense of grounding, rootlessness, and you find someone that speaks the same language as you, you’re going to find your grounding. You immediately trust this person more than you’d trust someone else, in a weird sense. When I did this performance, it was interesting because I would start code-switching – not because I wanted to, but as an unconscious thing to have the other person understand me better. Or to help the other person to feel more comfortable. Hence for me, the Creole and accents interest me as a means of creating bonds and connection with one another.

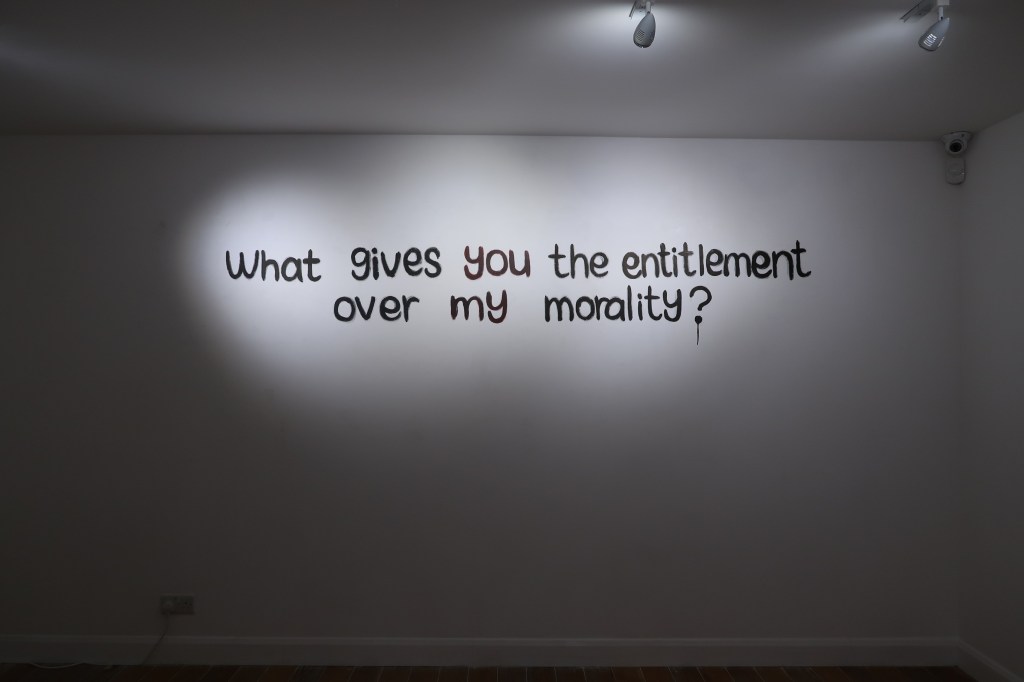

In my performance ‘I love my country, not my gahmen’, the word ‘gahmen’ is actually a Singlish word for government. ‘Government’ is a three-syllables word, and we’re trying to be efficient so we cut it short into two. But as an outsider, no-one’s going to know what this word means instinctively. So if I show that work in London, and a Singaporean person catches it, they’re immediately going to know that it’s a Singaporean artist. The word ‘gahmen’ is really interesting. It was a word used to go under detection by the government online. The government obviously knows about it now, but it used to be a way of escaping detection. I think it’s interesting, these play on words, capturing words I feel are interesting. Certain bits and pieces I pick up, or at times I find uncomfortable, even.

There’s another work called ‘On race relations and racism in Singapore.’ That work starts in the same way. I would listen to a politician’s speech, and I just started thinking – everything sounds right, but why do I feel so uncomfortable? I took the transcript and I started breaking things down. I kept finding bits where logically it made sense, but emotionally it made me feel like something doesn’t sit right. When you peel it back to see that it doesn’t make sense at all – it took its own logic and ran with it, strawman fallacies.

So yes, politician’s speeches and certain word usage – it’s all very interesting to me. That’s why I started doing performances based on language and word usage. And speaking of translation – lots of things get lost in translation. You can translate the meaning of it, but you can’t translate the emotions and history encompassed in that one phrase. Or the jokes, for example, the humour doesn’t translate.

MC: It’s very interesting, and it goes into all aspects of your work – the personal and the political.

LL: Yeah, I find that it is similar – to parent and to govern. If you were to ask me what is the ideal government, or the ideal politics, or political landscape, I think there’s no right answer. There’s no one right system that works. I think there is a similarity, if I were to put it in terms of the Singapore political landscape, which is that the government tends to parent the people. There are certain things you can see, and certain things you can’t see. The government would determine that, and that being said, the same goes for your parents, saying that you can do this or you can’t do that. However, where would the line be – when do the parents govern the kids, and when do the government parent the people?

MC: I agree. It has been very interesting to hear you talk about your work, especially after spending time in Singapore. I would like to finish by asking you for three names of artists who inspire you, influence you, or have an accordance with your work.

LL: I would say first Rirkrit Tiravanija. He’s a Thai artist, and he is very important because people come into direct contact with his work in the gallery space. He uses food in the gallery context, and social intervention. He did this work where he made lots of Thai green curry inside the gallery and served it to visitors. Then I would say Ho Rui Jia, who makes videos and performance lectures about Southeast Asian economics and landscape. He helped me come to a consensus on the validity of the performance lecture form, and also that it would be narrow-minded to only view the Singaporean political landscape as it is without the macro picture. Then finally I would choose Jenny Holzer. She creates these text-works full of truisms, one-liners and humour. It inspired the direction of my work a lot, especially my work ‘Tips and Prevention Against Sexual Assaults’. I think the style is so effective because the sarcasm, irony and humour reaches people easily.

Leave a comment