MC: Could you tell me how you first started this journey, and when you first began to consider yourself an artist?

CSX: I started thinking about pursuing a creative career when I was in school. I went to an arts college called Lasalle College of the Arts right after O-Levels. I actually went to the school thinking I would pursue fashion, but I somehow managed to make friends in Fine Arts. I didn’t even know what Fine Arts was, but I did enjoy going to galleries at that point in time. The course focused on artworks that you might see in museums and galleries. And my friends were like, just join us! So I made the switch and I’ve never looked back since. I have definitely made some changes – I started out doing painting, and towards the end of my diploma I decided to move more into installations with kinetic and electronic elements. That’s where I am now. But I guess I only considered myself an artist as I was graduating and starting to do projects beyond school.

I never planned to become an artist. In Singapore we are pretty practical, in the sense that we are always thinking about how to do something with the goal of earning money. That’s a question that anyone faces in any industry, but particularly in art because there’s no prominent transactional aspect to it. I was almost a hundred percent sure that my practice wouldn’t make me any money, so I was really prepared to become an art technician or gallery assistant, just to work somewhere within the creative world of art, within the ecosystem. But when the pandemic hit, it opened a lot of doors for me. A silver lining of the pandemic is that there was a turn, a focus on tech-related art and artworks which have some sort of conversation with the potentials of technology. A lot of producers were shifting their curatorial focus into those realms. That definitely did give me a leg up.

MC: I went to see your show at Starch Gallery, which was fantastic. A group show with three other artists. I was wondering if you could talk me through the two installations you exhibited – how they came about, and how they link to the other works in the exhibition.

CSX: The title of the show is called ‘A Gathering of Tomorrow’. It is a show that addressed Asian Futurisms, and it was curated by Gillian Daniels and Kristine Tan on their curatorial duo called Proto Projects. They were both interested in the kinds of potentials of futurisms that are more regionally focused, because we are so used to sci-fi references from the West. Even within sci-fi, there’s a very particular skewing of perspectives on Asia and the East from the West. So I think this exhibition was an opportunity for us, as Asians, to tell our own stories about the region and what we hope for the future, and to comment on where we see the world heading.

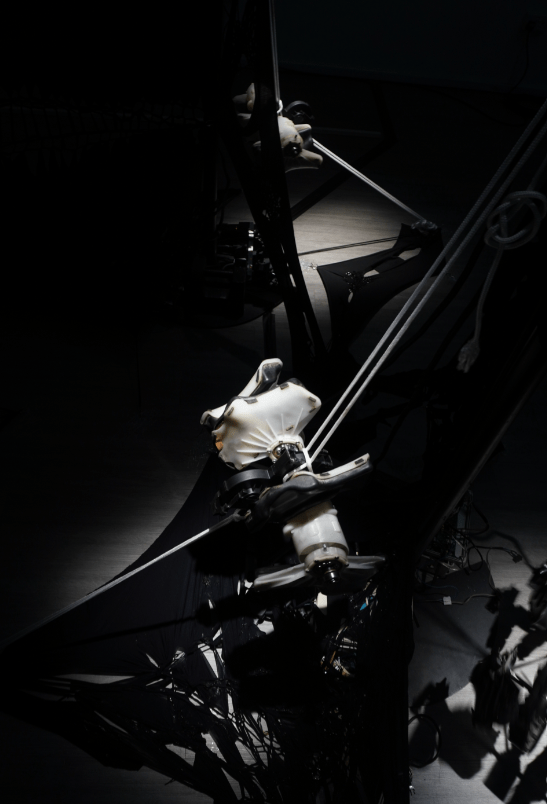

For myself, I showed two works. The first work is called ‘Prosthesis’. It is a work I produced earlier this year, but it is a series I have been developing since 2022 thinking about machines that are close to us physically. When I was thinking about that, immediately, I was thinking about massagers. It’s a bit strange, what kind of role they’re made to play – to replace or simulate the act of touch. That is something which is so intimate and produces a closeness between one human and another. It’s so strange that, instead of initiating or asking for that touch from another person, you are asking a machine to touch you in that way. For me it was a question of whether it successfully simulates it, and also if it is so difficult to ask for that sort of closeness from another human.

The Asian aspect comes in quite closely. In Asia in general, and in Singapore especially, there’s a wave of massager brands. In Singapore we have this massager brand called OSIM. It is a very prominent, large company, and we see the advertisements everywhere. It reflects on the idea that massage is part of Asian culture. If you see massage parlours all around the world, they’re all either Chinese, Thai or Japanese. I think there is something about the origins of massage that points towards Asian labour, and an Asian way of perceiving the body as well. That is something I am trying to continue in my practice, in this work.

MC: To speak some more about intimacy – the feeling that human connections are being lost to technology. Has that idea fed into any of your other works?

CSX: I always feel that technology has the ability to bring us closer and alienate us – at least, create some distance between one another. My works are a way to extract our everyday elements like appliances and objects, and to try to alienate them in aesthetics and form. For me, that alienness comes in experiences when someone approaches the work and finds the objects somewhat familiar, but are not able to pinpoint why. They should be able to spend some time with the work before they recognise – oh yeah, that’s the thing that I use in my house. The idea of intimacy comes into tension with familiarity and alienness. I’m always trying to play in-between those lines, and also to ask larger questions about our own attitudes towards technology and the ways in which we use these devices and systems.

I have an artwork right now at the Science Gallery Melbourne, called ‘latent’. This work started out with me discovering these massagers. Unlike the ones that you saw at Starch space, these are pneumatic massagers, which have these airbags which press against your back and kind of inhale and exhale, almost like they’re breathing. It’s really strange because it is this appliance which is massaging your body, but is also acting like a certain organ, our lungs. In its former life as a back-massager, intimacy is formed through the touch, but can also be created through the act of breathing.

MC: Yes, intimacy in the form of recognition of the humanness in this machine. I noticed in the work in Starch Gallery, the massager is moving in a very human-like way – almost a shiver or a spasm. It makes a sort of clicking sound.

CSX: My curators pointed out that it sounds like it is cracking its body, its joints. It’s really trying to wriggle.

MC: You can’t help but humanise the machines that you create. To give more context on this work, you have taken the cover off a massager chair, and the piece is just the inner moving parts. In the background you have material stretched out like skin, like a membrane.

CSX: I wanted to try to rethink what skin and bones and joints actually are. So I gave it a new appearance and form.

MC: That links well to your other installation in the show, which is made of these pieces of metal which are used in heart surgery…

CSX: That work is called ‘memory’. It started out with me responding to the title of the show, ‘A Gathering of Tomorrow’, which immediately made me ask myself the question of what we will remember today which will continue on to tomorrow. That’s the future – tomorrow doesn’t feel so far away, but it ultimately accumulates. Then I discovered this material, Nitinol. It’s made out of nickel and titanium, and the last ‘NOL’ stands for Naval Ordnance Laboratory, which refers to where it was developed. Classified under a family of materials called ‘Shape Memory Alloys’, the title of the work, ‘Memory’, refers to its ability to remember and hold a state. The act of remembering feels like something that only a living organism can do, but I think it’s really exciting to think about how other materials can remember or recall.

How this material works is that, in its static form, it can be deformed and moved around like a normal wire. But when you pass heat or electricity through it, it is able to recall its old shape and return to it. That recalled shape can actually be ‘remembered’. The ones that I got, the remembered state that they had is that they would just coil up into a tiny spring. So I created a mechanism in an X-formation with these two springs, and I would pass electricity through them at different times so that one would contract and coil up whilst the other would relax, and then the other would coil up. It was me trying to recreate the muscular tendon. The material has often been called an artificial muscle because it is very strong, and it can be engaged or relaxed like a muscle. Again, it’s me trying to allude to a body part, and bodily function. The way that it moves also is something that you might see, imagine or feel in nature and in ourselves.

MC: That’s a fascinating work. I’m interested in what you’re saying about temporality. That exhibition explored it in such an interesting way. The reading list for the show included all sorts of classic science fiction and speculative thinking – your Donna Harraway, your Ursula K. Le Guin – but also a lot of science fiction and thinking from Asian Indigenous peoples. To go back to this thing about Asian Futurism, I wonder if you can compare it to Afrofuturism as a method of thinking about the future buried in a pre-colonial foundation. This idea which challenges the primitivizing of a culture. How far did you engage with these texts and ideas?

CSX: I think that in Singapore, at this moment in time, the re-examination of histories is taking place. Every year on National Day we continue to perpetuate that idea pre-independence and colonialism, not much was happening on this island. But if you even peel just a bit back and ask the descendants who were here in the early days of independence, you would know that there were many migrants here a long time ago who became indigenous people. Actually, Singapore can be considered the heart of the Malay archipelago.

To further contextualise how I understood these conversations. I was recently part of this art walk at this place called Kampong Gelam. It was an art organisation, OH! Open House, which often commissions artists to come in and speak to the stories of neighbourhoods in Singapore. Kampong Gelam was actually a village and also a point of entry for most people who were coming to Singapore from Indonesia. When Singapore got independence, the people who lived there were slowly bought out. Now it’s a huge site of tourism, and all the people who used to live there got pushed into housing nearby. To that whole process, in working with them and speaking with them, they were the ones that observed maybe fifty years of immense change. People once had businesses there – now it’s all international cafes and Instagram spots. I think that change is an example of this being a site of contention. So many stakeholders coming in. Who gets to have a say in who resides here?

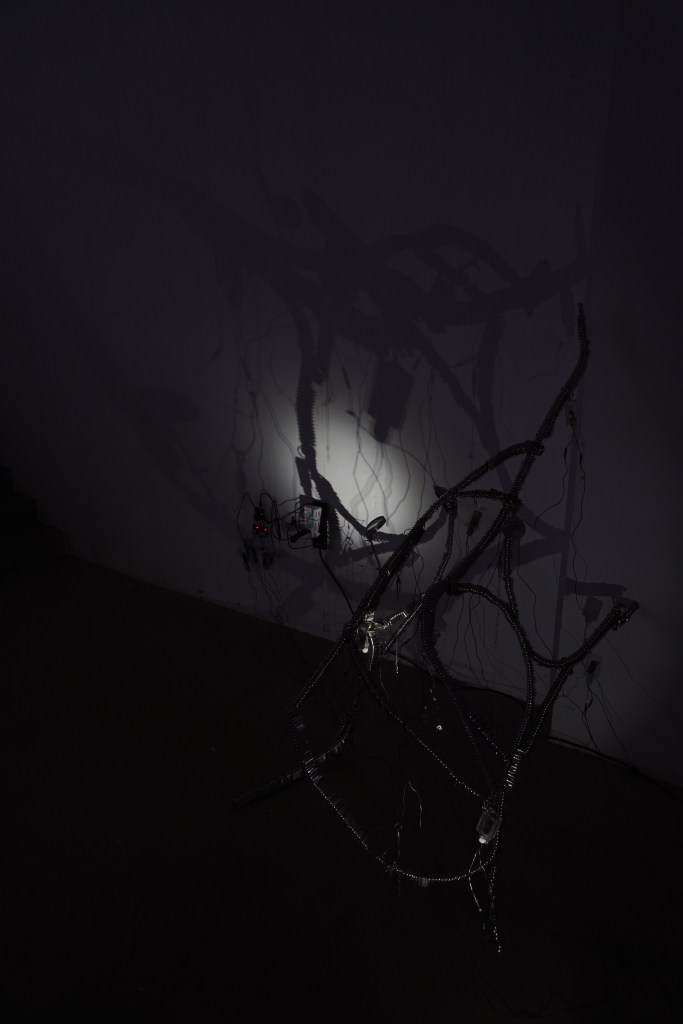

There is a very small part in the centre of that whole area, called Pondok Jawa. It has this banyan tree. A banyan tree is part of the Ficus family and it’s a parasitical tree, so it requires a host tree to grow on. It has a lot of these aerial roots draping down and it can grow really big. About two years ago parts of its branches started falling. So they chopped it down, and this revealed that it had been growing around this really old brick pillar, probably from the early 1900s, from the old building that used to be there. For me, this was so exciting – this tree consuming and growing into a pillar. But at the time, there’s the context of Singapore being so land-scarce. Every bit of land is accounted for, so it was so rare that this pillar which had existed for such a long time could have remained there untouched.

My work, VINES, was in response to the site. It is a series of sculpted mild steel, as well as some water atomisers. It would sort of try to water the area at certain times, pumping water up and misting the area. It surprisingly worked – I wasn’t sure if anything would grow because the area is pretty hot and on the side of the road, and it was pretty much a dumping ground for people’s rubbish. It was funny because, as I installed the work, the authorities came and said they needed to demolish this pillar. It was already semi-demolished. People would tie red strings around the tree, as part of Chinese spirituality. So, from this bare area, in five weeks actually so much grew. My intention was to bring attention to the site itself, which has its own way of responding. I’m trying to negotiate my work’s existence within this natural thing.

MC: The wires that you’ve put in are so similar in form to the actual vines that are climbing over the tree. It’s a real synthesis of technology and nature. That’s a really amazing example of using technology for good, to bring us closer with the natural world around us – and with culture and tradition too, with the prayer strings. I was wondering if you ever consider your work to be a kind of prototype for the future?

CSX: Yes, I think so, in some abstract way. I’m always thinking about what we already have and what we are already used to, to try and find ways to look towards the future. I think we are closer to our ideal future than we think. I don’t feel that we need to invent flying cars for our world to be this optimal version. Most people want to live in a world where it is possible to exist in harmony with other humans, other organisms, plants, and ecosystems. To be sustainable and live sustainably – this is the hope for the world, at least within the region. I started looking into working with solar power because me and artist Victoria Hertel have a collaborative project which is to do with the weather, and also thinking about urban structures. That’s how I got into the logistics of thinking about making work outdoors.

MC: I was going to ask you about your collaboration with Victoria Hertel and Yun Teng Seet. Could you talk a little bit more about how you work together and the kind of work you are creating?

CSX: Our conversations started in 2022. Victoria and I had a desire to work together because we realised our practices have a lot of similarities in the way that we look at things and choose our materials. We are both installation-based, and both work with electronic and kinetic elements. We then brought on Yun Teng as our curator and also as a facilitator. She did a lot of legwork in giving us a third perspective on both of our practices and how she sees them coming together.

So the three of us together started thinking about the idea of rust. The idea of sacrificial protection also came about – a corrosion protection method that is used to combat rust on metal. Especially in an ultra-humid climate like Singapore, where rust is inevitable, we are trying to think about what rust does. This rust represents active interfacing with materials. Metals also appear to be inert, or resistant to any external forces other than really intense brute force. Actually, metals can slowly react in a volatile way to the atmosphere.

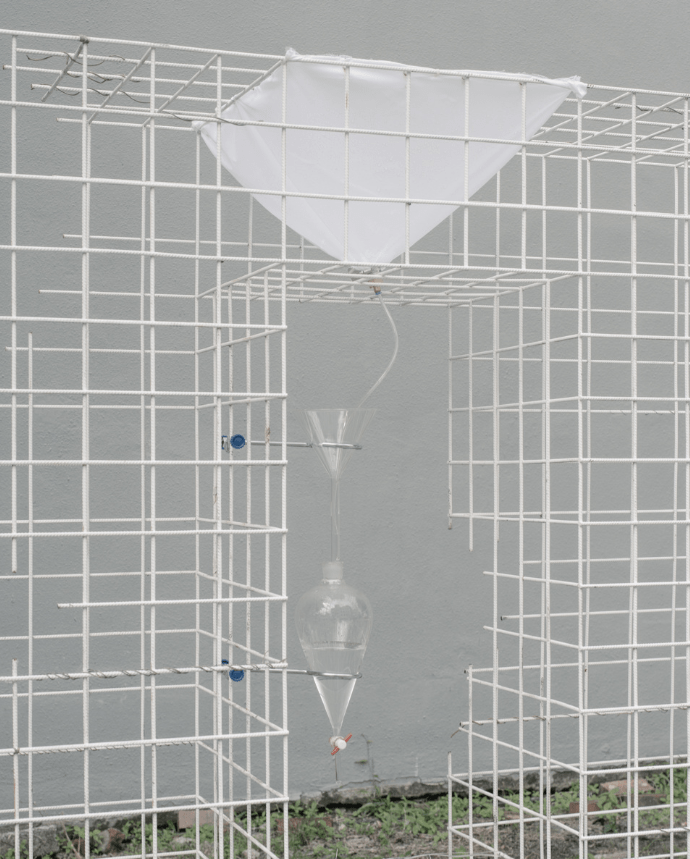

So we started to appreciate the material, thinking that the rust looks so beautiful and flaky, and it looks like skin. Again, giving it some sort of organic or bodily quality. But then we thought, wait – so many of our infrastructures also have metal in them. Because metal is the skeleton of our highways, our buildings. What happens then? Does the rust affect the structural integrity? Is this a sustainable way to live? So it became a conversation about how there is a vulnerability to our seemingly robust and sturdy urban structure. From there, we decided to look at urban building materials, creating systems that use urban materials like carbonised steel sheets, reinforced bars, and concrete. We also added a weather-dependent element through sensors. Through these solar-powered systems, we had light sensors and temperature sensors to react and build systems which create circularity.

One of the installations used a water-collection system. We found these reinforced bar structures at our school – serendipitously they were throwing it away. So we created this makeshift rain-collection structure, with these separation funnels and vessels which were inspired by Victoria’s practice. Then I added these atomisers, so the water would trickle down and get re-released into the air. A water cycle.

In this other work, there is a vibration motor attached to this galvanised sheet of metal that we found and worked into a cocoon shape. We soaked it in vinegar to remove its sacrificial protection layer, to allow it to be raw and then the metal would react a lot quicker to the air. So you get these beautiful, super rusty bits. Throughout the course of two months, a lot of rust would flake off and a new skin would form. At the same time, there’s this light sensor which would vibrate it and shake the crust off.

MC: So, it becomes like a living creature. Shedding its skin. I love the way that you work with materials. You have this really empathetic relationship with inanimate things – you give them life and feeling and a sense of future. Even the way that you speak about appreciating the metal for the qualities that it just naturally has – it’s a nice way of thinking about the kind of relationship that all people could have with the environment. A more considered and less consumerist and wasteful relationship with the world around us. But to move away from the material and corporeal, I wanted to ask if you engage with the virtual world – especially AI – in your practice?

CSX: Not so much. But I think it is an important question to ask – the idea of software and hidden systems behind the software. But for me, I don’t use any software myself beyond just very rudimentary coding.

MC: I guess the reason I ask is because I know that information and communication is important to you, as an aspect of this intimacy idea – the intimacy between the human world and others. The kind of relationship we have with the world around us is changing so rapidly. Also the idea of time is being skewed by AI and being on the internet a lot. Can you see this change coming into your work?

CSX: I guess so. On a personal level, I am a chronic doom-scroller as are many people around me! I cannot deny that it does skew my perception of time and space. I think, to speak about information, I can relate most to a book that I read called ‘Non-Things and Upheavals in the Lifeworld’ by Byung-Chul Han, a Korean philosopher based in Germany. In this book he talks about how our society is moving into informatising everything. Objects are not just objects – objects have values and signifiers linked to them. I guess a meme would be part of this new ecology – for example, if you wear a certain brand of clothes it will be recognised by certain people as signalling some kind of message. You’re not just wearing clothes, you’re not just using objects. That informatisation of things, especially with the way we are engaging virtually, is really transforming objects from the way they function for us on a physical scale to also what they signify or what values they represent.

At the same time, there’s also that distance from touch. From the start of industrialisation, we rarely make use of our hands – we outsource that to machines. We don’t really understand how things work anymore on a tactile level, what their qualities are. We’re not physically interacting with things, so we don’t know what qualities to look out for. That creates a lot of distance and makes us informatise objects because of our lack of familiarity. It’s a return to materiality in a way – because we are so distanced from the act of making and production, we turn to other ways of creating relationships with these things. This affects the way we work in the virtual and the physical world.

MC: That’s so fascinating, especially in the context of Singapore. Singapore has been described as the air-conditioned nation, where people have total central control over their environment at the expense of personal autonomy. It’s a nation which is supposed to become the first ever Smart City, where AI is intertwined with every aspect of the infrastructure and daily life, making data the most valuable resource. At the same time, Singapore is super industrial – walking around here, things are constantly being built, there are factories and building sites everywhere. And the money comes from the infrastructure of oil. So, the two sides are in tension with each other, virtual versus material.

CSX: Everyone thinks of Singapore as the future. But I guess, because I’ve lived in Singapore my whole life, my perception is very different. It’s hard to see it from a tourist or even a business perspective. For me, we are a country with short-term memory loss. Buildings come and go so easily. Even the names of streets and roads change so quickly – the names I know will be completely different to what my parents know. So, I feel like it’s hard to hold on to things and spaces and ways of living.

MC: I guess that’s why corporeality is so important in your work – the grounded-ness, body-ness, thing-ness of the environment. I would like to ask you where your work is headed in the future?

CSX: I think right now I am taking stock of what I’ve done in the last five years, and that might turn into a book or a blog. Research-wise, I’m definitely interested in pursuing this idea of labour delegation – what it means to have all these mediatory systems like appliances and software. Finding more parallels with the massagers or shape-memory alloys, and to find new ways of thinking about movement. In machines, we are always thinking about the movement of the rotation in a motor. But I am thinking about finding less orthodox ways to create movement beyond the rotary. Also going backwards to find out why the rotary movement is so common, with ideas of electromagnetism and how the body cannot make a full 360 turn in any part. There are a lot more historical and technical explanations to do, and I would like to also explore the histories of different kinds of movements that address that tension in our body. Exercising and sports for example. Cementing these explorations which might inform my installations – that’s where I’m headed.

MC: So, my final question is to ask you for three names of contemporaries of yours, or anyone who you find inspiring or whose work has some accordance with yours.

CSX: Victoria Hertel. From working with her I have realised that, even though we address very similar things, she has a very different focus. She speaks a lot about surreal technologies and seeing the senses as a way to capture information about our space. Perhaps she can also speak further about information and the virtual. She has this work which is about capturing the scent of an individual– capturing different values in the air, like someone’s breath, and translating it into the virtual through visuals on a screen.

The next person I would mention is Ashley Hi. What she does with her company Feelers is quite exciting as well. They’re partly focused on education and community-building to create the technology. A lot to do with the questions I am also asking about sustainability and climate change using technology. Asking how we can use technology to see the world that we want to live in.

Lastly, Jo Ho. She does a lot of things. She is a multimedia artist, and she does a lot of VJing – Video Jockying. She works with a lot of generative AI, within the virtual sphere. She trains neural-network models to produce certain videos and images, and she’s really interested in the idea of gore. Her textures and things are always related to gore and bodiliness. She’s also part of a curatorial duo with another artist called Kapilan Naidu, called Jo + Kapi. Both of them curate artworks in the tech and virtual sphere. She’s very cool!

Links:

Home – Si Xuan (cargocollective.com)

https://www.instagram.com/protoprojects

Leave a comment