MC: I would like to start by asking you to tell me your journey of becoming an artist. When did you first start to call yourself an artist?

BAK: My father, he’s from Klunkung which is the Eastern side of Bali. He is known for classical Balinese art there, called Kamasan painting. It’s a very classic way to make a painting in comparison to Western art, and also Balinese people use it as part of their ceremonies. My father knew how to paint that as part of his tradition, passed down through the generations. So I was familiar with the art-making process from very young. But I did not live in that village – I lived in Sanur, which is a very touristy area. During my childhood, it was the beginning of the tourist boom in Bali.

For high school, I went to a high school that was specifically for art. Yes, Bali has this – Jogja also has it. During that time, they divided into only two majors – traditional or modernism. I took modernism, and along the way I started to hang out with artist friends and learned how to paint and how to make money. This is what I felt it was like entering the art industry in Bali during high school: you need to know how to create beautiful paintings in certain sizes, and you just need to sell it to the art shops. So I learned how to do watercolour. There was this very famous watercolour art style done by a Bandung artist who lived here, that is specifically made for the tourist market. It’s just about the aesthetic, about beauty.

MC: So when did you begin to introduce a more critical edge into your work?

BAK: During my university. I think I didn’t have the critical environment here, with my family or with my friends. We just don’t have that critical thinking habit or conversation. But when I went to Jogja and applied for the university, I went to this Balinese community. Because people from all over Indonesia come to Jogja for education, there was a very high demand and high competition during my time. Especially for fine art. Because of that, each community (say Balinese, or Pandang, or Sumatran) had a responsibility to train those who had come from their place, before the entrance test. It’s like a two week camp. But it was army style! All the experience I had here in Bali was useless there. Even just how to draw an aesthetic line, it’s very different. It was not easy. I went there with twelve other friends from here, and during those two weeks four of them quit. And this was only the preparation for the test! It was super intense. That was where I first realised that the art that I knew was very different.

So out of my friends, only eight were accepted. I was one of them. Not all of them were accepted into painting, because you needed to have an Option B – maybe printmaking, or sculpture. So I got into the painting course on the first try. I felt lucky there. I started to hang out with new friends and started to understand about concept and critical thinking.

MC: How would you say that your work has developed since then?

BAK: Basically, it is doing my work through studio practice. I develop an idea and then execute it in the studio. I studied for my Bachelor for seven and a half years, which is the limit of time before you drop out. During that time, I also actively exhibited my work outside of the uni. I started early actually, I think because of my experience making art for the tourists.

MC: You already had the business mind…

BAK: It was not so much the business mind yet. Because in Jogja the competition was so tough, and it is very progressive there. For example, if I went to my friend’s studio and he had new and exciting things happening there, it would trigger me. Over there, it is hard to try and find your personal style. I tried many different kinds, doing a lot of experiments. Art students need to have the studio – you can’t just rent a room; you need to rent a house. So I was sharing with a couple of friends to rent one house in my first two years. In that time, I was really exploring my own style. Also, on campus, you would have to present your artwork and people would criticize. This began my understanding of the content of the artwork.

Although I am Balinese, I like to hang out with people from all over Indonesia. I was exposed to many kinds of characters, and it led to a broader network of friends.

MC: You can see that in your work, in the way that you are exploring the idea of a national or ethnic identity. You are talking about what it means to be Balinese, not just from within the Balinese context, but more widely.

BAK: Yes, at that time I started to understand the identity trap. The cultural identity trap means that you only hang out with people from the same culture, the same ethnicity. So, I had shows, and some shows were considered good shows, and I met lots of writers and curators from Indonesia and overseas. The good thing about Jogja is that it is where a lot of important art is made and the contemporary art exhibitions are good quality. It is a good place for networking. And, unlike my Balinese friends, I would hang out with many different people so I had more access and opportunity.

I did my first proper solo show before I graduated. My professor knew of my career outside of campus. I found out that I am not a very academic person, because when I had to write a paper I found it very difficult to start. But I had to present a certificate to my parents. I got support from my godparent Ny. Pat and Tn. Joel to paid my school fees for a few years: they are from US and lived in Bali at that time, because my parents had limitations to support my education. Half way my uni journey I managed to funds myself and survive until graduation, and from there I continued my practice, based in Jogja for another six years. Then I met my ex-partner. She’s Singaporean, a photographer. This was the first time for me to do collaboration, and also the first time for me to do art outside of the studio. This developed my sensitivity to community art.

At the time, I worked with batik makers from Klaten – a village between Surakarta, Solo and Jogja. We worked with traditional hand-printed batik and also natural dyes. The practice was almost extinct because the life of the batik-makers was tough, and also the technology of printed batik was also destroying the market. There were also regeneration issues, because not a lot of young people want to do that job, because it’s not cool. So we are facing several threats to this craft that, as a nation, we are very bound to for our identity. At this time, Malaysia also claimed batik as being owned by them.

But I met the real situation, the real issue, with real people. Very different from my studio experience. Because studio experience is based on my observations, maybe influenced by news or other things. I have an idea, and I execute it in my painting. And I found out that sometimes I become exploitative with certain issues. For example, if I am talking about social issues in my painting, I don’t really contribute to helping the issue itself. I am just talking about it, and I make money from it. This is a dilemma for me. I had problem with my studio habit, because in the studio I am the one who decides what the work will look like. In the beginning, this would also happen when I was working with the community. But it is unsustainable. I still come to the community as an artist – I have the idea, they have the skill. But they develop my idea, and when that particular artwork is done, that’s it. I felt there was something wrong with this method. So I started to be more open with the community, and to find out what was the daily things around them that had value to them and could benefit them.

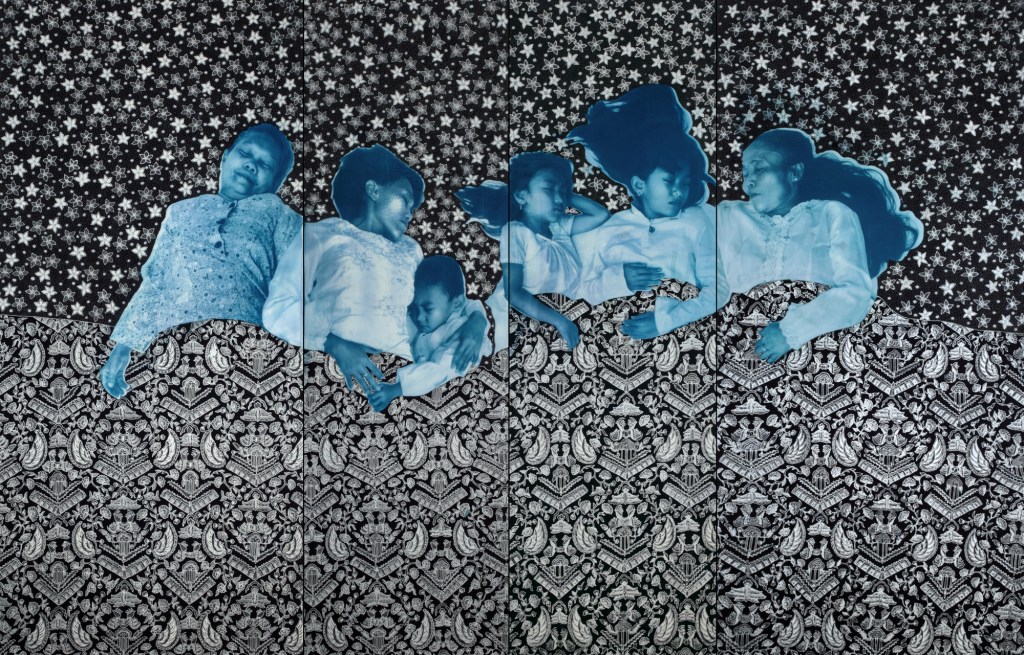

To them, it’s just everyday things – for example, like the batik motif. Classic batik motif is traditionally only for the royal family. They were the one’s who made it, but they can’t wear it. I just think that they should have experience wearing it, but it is against the tradition of the palace. So, I tried to create the experience through the artwork itself. They made the batik which would go on top of their portrait. In the piece, their portrait with their family would be covered in the royal batik motif, as a blanket, for example. The idea, during that time, was that two big countries were fighting over the claim for batik, but no-one even looked at who was actually making the batik. There are real people behind it, and their life is not easy.

MC: I’m interested in the way that you use a lot of royal, grand, beautiful details in your work. You make these portraits of workers or working class people, but you’re dressing them like kings. It’s an interesting way of rewriting history. Is that what you consider yourself to be doing?

BAK: Yes. This series also linked to my personal life experience. In Bali we have a caste system, and my family is from one of the high castes in Bali. But then, in my situation, I am considered an outsider. I just want to be a normal person. The caste is just title, but the quality of life of those people who have that caste… it is not guaranteed that they will have a good education, because of the colonial system, also. I had this sensitivity from a young age.

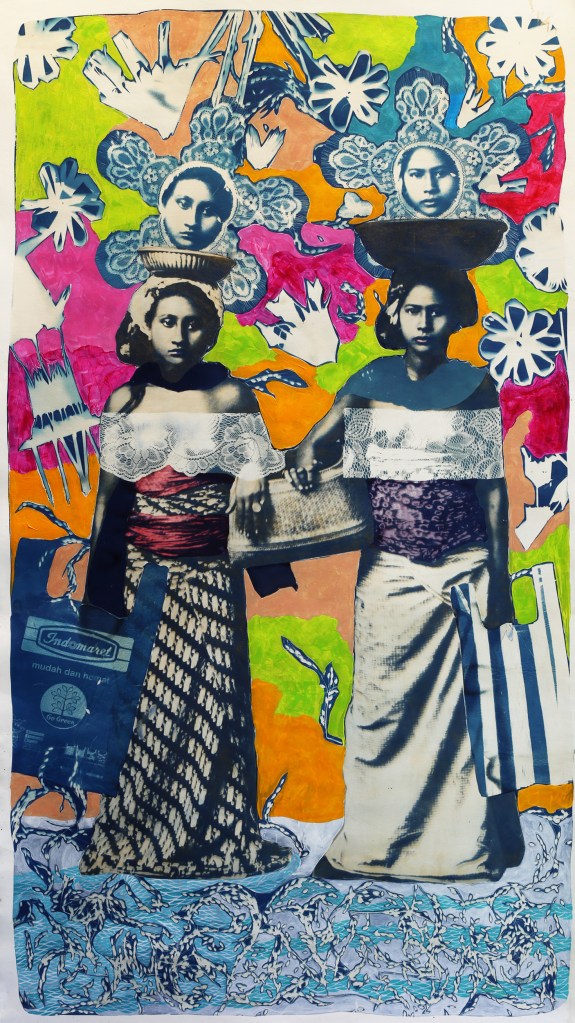

I think with the current series, I work more with colonial archives, but it is completely different story to the community project. I have an interest in marginal issues, or marginalised community, but it is applied in different ways in the community project as to studio practice. I recently came back to my studio practice after three or four years focusing on community projects. I had this experiment from a long time ago using colonial archive, particularly visual archives, photographs. I saw lots of information in the photograph itself. If the photograph is of someone from the royal family, then it will have the name recorded. But for common people, they don’t record the name. There is a difference in interest from the photographer – they more value cultural identity. From there, I had this thought that the success of the tourism industry in Bali was actually because of those figures with no names, because they produced a lot of these images to promote the island. Without them, I don’t know how Bali would be. So I had the idea to make a series called ‘Anonymous Ancestors’. That was the start of my artwork up to now.

MC: Can you describe how you presented those figures in those paintings? What techniques did you use to represent these un-named people?

BAK: I used cyanotype, because I’m interested in translating data by using the sun. In the past, those photographs were also made using natural light.

MC: So it’s a way of connecting you, in a very real way, to the anonymous ancestors?

BAK: Yes, using the sun. I realised that, yes, we are all under the same sun. And I realised that our idea of time is based on how many times the earth rotates around the sun, how many times the sun rises and falls. I tried to develop the image in sync with the understanding of that system of time. From there, I saw many different interesting things. It has allowed me to create the feel of a time gap between that year and this year, between past and present. This time gap actually produced the story that we understand as history today. And also a lot of stories that have no place. They become untold history.

From there, I just kept going with the creative process, with the cyanotype and the archive, and this has allowed me to have my own imagination about the past. My understanding of history is not only created by some powerful people, with power to shape it, but also marginalised stories, small, small things. I can play with that. That is why I still continue.

MC: I’m interested in the use of the colonial archive in your work. Because when you go to an archive, you think of it as always telling the truth. But when you work out how an archive works and how it was created, you realise that it’s just one story. It’s interesting to see how artists use creative methods to tell the stories that are missing from the archive. There are always going to be things that you don’t know and cannot find out. So, understanding that, what ways do you use your imagination in your work to fill those gaps? Is it a question of fantasy?

BAK: I would say I am fantasising the situation with time and the archive. It’s like this: since the internet, we get exposed to this digital data. One time, accidentally, I saw some Balinese photograph archive online. I tried to find where the resource came from – this big institution in the Netherlands, which kept lots of artifacts and archives from Indonesia from colonial times. There is always this story of how those objects ended up there, but this is another story.

Understanding the archive, you can use lots of different perspectives to look at it. But for me, I choose to work in terms of the characteristics of the material. Although I am a painting, I try to present the material as part of the concept itself. Like, if I want to talk about history, then I use the archive. But I need to find a way to translate it that minimises manipulation. For a painter, it is free – I have an idea, I paint, I deliver the concept. But I want to try and find a technique that can maintain that feel of the material of the archive.

Even the process – that’s why I have to use sunlight. Because I harvest these images as digital data, and then if I want to translate them, I need to use the same source – which is the sun. Cyanotype technique is one way to facilitate that. Now digital technology is so advanced – you can create perfect images. But my goal is not just to make a perfect image. For me, the process itself is so meaningful. When I do cyanotype I need to check the weather forecast, I need to make sure I have the sun for a certain period of time, and if there is a cloud I need to calculate the wind direction. All these sensitivities I feel are part of the concept itself. But for people who see the complete piece in the exhibition, they only experience the visual. But I think the process is more rich than the visual alone.

MC: I do think you can get a sense of that richness when you look at the final piece. It has a depth which shows all the processes which have gone into it.

BAK: I think so, but I still feel I need to provide a long explanation. There are so many things going on in the process, I cannot explain it in one sentence – so many layers.

MC: Could I ask you about your current exhibition in KL? I understand that you are using AI as a tool, which is very interesting. What kind of effect has this had on your practice?

BAK: Going back to my effort to limit manipulation, I had this idea a long time ago to imagine the descendants of these anonymous ancestors. Sometimes I imagine that I am one of those descendants. But this is just my fantasy. For me to translate that, if I create with digital imaging, it is too much manipulation for me. Then AI came, and I tried to understand what it can do. I realised that this is the right tool to execute the whole idea. AI works based on data, and I am harvesting digital data about the archive. So I input this digital data into the AI technology, and let it generate based on all the information that it has.

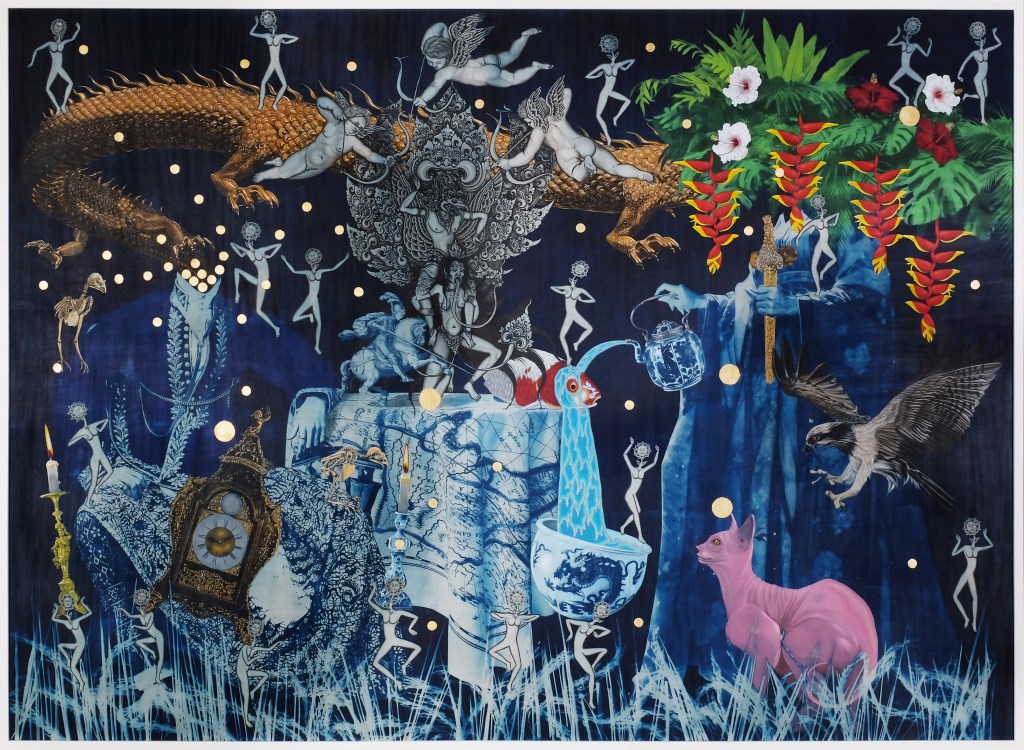

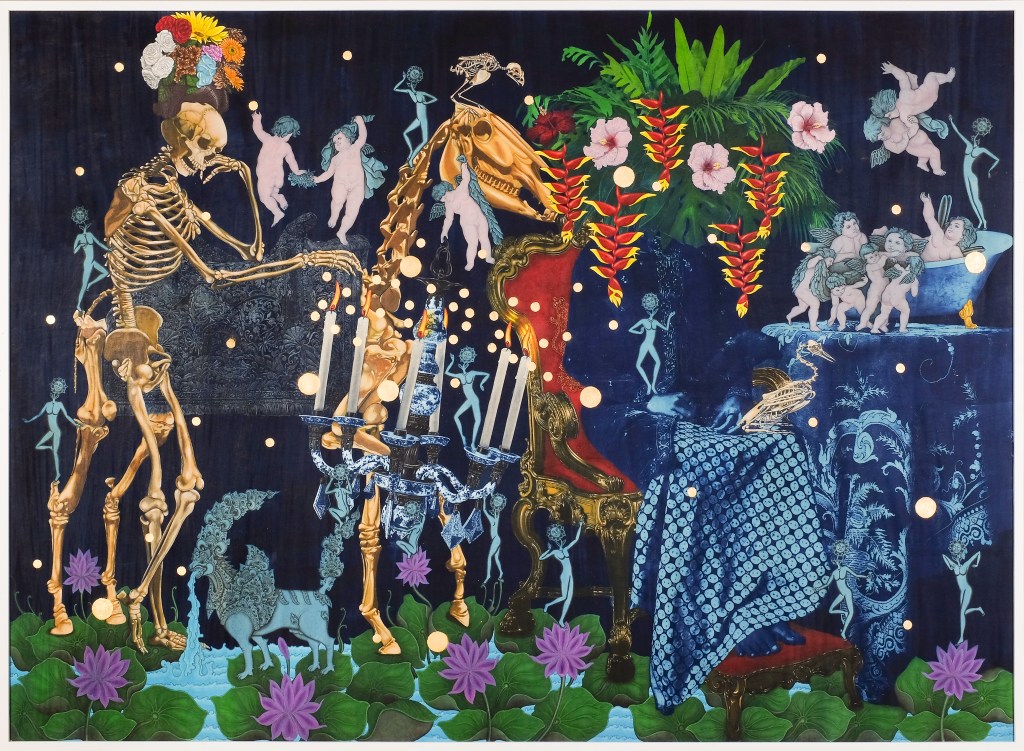

For example, I input some face of a person from the archive, and I create a prompt – what will the third-generation descendant of this person look like? After several tries, I can get a person who looks very identical. So I use the face, and I create the stories of this third-generation person. I capture them in my paintings living a better quality of life, a higher status – all the abundance that surrounds them. Also I put the perspective on this third-generation who are learning from their great, great grandparents to maintain their wisdom and way of life – even during the colonial time, the difficult time. These values shape them until today, allowing them to have a better life.

I choose to talk about colonialism and try to escape myself from a victim mentality. I don’t feel comfortable talking about colonial times when I have to be on one side – like a victim, where you start blaming. That’s an endless loop. I want to use my imagination to see how it is part of the process. I am aware that we are just all under the same sun. We are growing up like a flower. I have a lot of figures with flower-heads. The process of growing a flower is very far from the final look of the flower itself – like, nice colour, fragrant smell. The process of growing that flower is far opposite – very dirty. But without that, you don’t have this flower. I feel it is also the same with colonial times. And after the flower, you can get the fruit. Yes, colonial times were dark and bright at the same time – it’s a process. I think I need to build myself with this perspective. So this current series is my first try for this concept. It helps me to see the past and the present as something optimistic.

MC: Your use of AI is very interesting in what it does to our concept of history and time. When you create a face using AI, that is a person with no pre-history at all. They only exist in that moment when they are created. But at the same time, their history is every single image that exists on the internet. Their time is at once tiny and huge. Also, the fact that AI uses the internet means that it is taught by the same processes that create the archive – the same ideas of nation, ethnicity, and so on. Beliefs that we hold which get fed into the AI tool. So, within your AI-generated figures, you’re kind of mapping out living human history.

BAK: Now the current technology has allowed me to execute this whole idea. Without this technology, I wouldn’t talk about it because I am trying to maintain the characteristics of the material itself. It’s not about being excited about new things – it’s just reasonable for me to use it. A lot of people talk about technology and it’s use in painting sceptically, because painting has to be something that technology cannot be. If you just creating a visual, then maybe you can think that way. But this is not only about visual making – this is translating something. I really need to use these tools, because without them the translation will not be authentic.

MC: People always think that painting is the most authentic mode of artmaking, because it’s so material and you get your hands dirty. But looking at all the tourist painting in Ubud, for example – how authentic is that? It’s created by hand, by someone with real technical skill, but it’s just repeating the same images over and over again, with the aim to sell. You could just as well get a digital image to sell to tourists, and it would have the same effect.

But the reason I like your work so much is because your interest in processes of time and history translate so neatly with your studio processes.

BAK: I think I get this sense from the community projects, because they are process-based. The result is always a surprise – very different to the studio, where you know the sketch and design. With the community project, you are working with another human who has their own thinking, their own character, who have gone through a different life. I need to maintain their quality. I can’t just simply use them to execute my idea, like they are part of my material. And the result is always surprising. And the most important thing is that when I leave the community, the project will continue because they have a sense of belonging, it is part of their life. This gives me a lot of good feeling, and I try to translate this experience into my artwork.

MC: It’s very inspiring, and optimistic. I would like to ask you my final question, which is for you to recommend me three artists who you know, whose work has some effect on their practice.

BAK: I like surrealism, pop-surrealism. There is a space for fantasy, but at the same time it is also based in the current or historical situation, talking about the future. I like this feeling. So I like Salvador Dali, as the figure for that style. I like to see also traditional art in Bali, classic painting. Because they are usually talking about these Ramayana and Mahabharata stories which are from India, to get the moral and apply it to everyday life. I am interested in how the content of a painting itself can influence the context. For a name of a person, maybe an old maestro of classical Balinese painting – Mangku Mura. Mangku is a profession, like a priest, who facilitate ceremonies here in Bali. Each village will have a Mangku, a spiritual person who understands life deeper. The way they use that sensibility to make artwork also produces a different kind of feeling. This has become my inspiration. Then for visual… I have difficulty choosing a name, because I have difficulty to like or dislike. If I choose something, naturally I will be putting something else away.

MC: That is fair enough! Thank you very much for talking me through your practice.

Leave a comment