MC: I’d like to first ask you why you wanted to become an artist. When did you first start to think of yourself an artist?

AP: In the beginning I tried to follow my father and become a judge, but failed. I tried to go to law university, but stopped after one year. But, lucky me, I chose Jogja because my father was living here for study, and also my mother. I had heard the story of Jogja many times. So after I graduated high-school I just came to Jogja, only four hours from my city in East Java, and tried to follow my father but it wasn’t what expected. I spent some years trying to find what I wanted from myself. I love to make friends. In the beginning in Jogja I already met some people doing art – some painters, performers, musicians. There, I found a little clue that I can go into art, even though we have never had an artist inside my family. I think I’m the first. After three years, I graduated and spent my time learning about fine art, performance and visual art. It was good timing because that was when the digital era was starting to spread in Indonesia. I put myself to work learning about digital things – that was 1993. I found a new school, the Modern School of Design. I was interested in the Modern.

From that school I learned about computers, how to edit a photograph, design knowledge. I also started learning photography there – that was my time falling in love with the camera. You know, it looks easy, but you have to think to use the camera. I was taking photos related to design concepts. I used the photographs to make illustrations, book covers, posters. I cannot draw like others, so often I use photographs as a good solution for my ideas. I started with journalistic photograph, and I fell in love with it. I love photography which shows not only a moment but a story, and also gets the feel of the moment. I always use the journalistic method to create my design concepts.

MC: How has this interest in storytelling led into creating works like this? I can see that there is certainly a story here, but it is not journalistic in that it is a collage of lots of different objects photographed close up.

AP: But this is real. This is a car, this is corn, this is a toy. And then I create the moment. The title is ‘Happy Birthday Holy Day’. I invited my old memories to come to my birthday. Some of them are representative of a year I started to make, so this work includes artworks I made from 2005 up until recently.

MC: So, this is like a visual archive of your practice?

AP: I choose these ones, not all of them, because I need them to make a fixed composition. I can invite them all, but it will be too crowded. It is a different method of making photographs. I use a scanner as my camera. I put the object directly onto the scanner to create the image. In 2004, I lost all my cameras – I sold all my cameras for my life. As a photographer, I lost my gear but I was still thinking. That is my question – does a good photograph need to be made using a camera? Yes of course, but what kind of camera? Your brain is your camera. It was kind of a fun time to think, when I didn’t have anything – to think something new about photography in Indonesia especially. Photography in Indonesia was always about beauty. I was thinking about some great art movements in Europe and the US since the 1920s – the Dada Movement, particularly. I wanted to start from that movement – how did they make photographs? I did research on making photographs, technically, including using the scanner. With the scanner, from the real object, I can tell the same story.

MC: The interesting thing about using the scanner rather than the camera is that it takes away any kind of artistic manipulation. You cannot control the depth of field, lighting, shutter speed – almost nothing. You can only choose the object. Do you like relinquishing control over the final image?

AK: Honestly, I just wanted to create a tension in the Indonesian fine art scene. Maybe twenty years ago, photographs were not included in the fine art scene in Indonesia, and this made me jealous. To go back to my old story, after I finished learning Modern Design, I was accepted into study in Art College for photography for four years. The good options after studying photography were to become a lecturer or to become a commercial photographer, or a journalist. But I didn’t want to lose my energy over the four years, so I decided to become an artist, using the photography as my medium for the first time in Indonesia. Photography in Indonesia at that time – it was not sexy, it was not good. Disaster for me! I met a tension, a need to create a different movement. Something out-of-the-box. It was not easy. There were pros and cons. In the beginning, a lot of people, photographers, said that that’s not a photograph. But others – small people, little people – felt that this was something. So, the final decision was up to me – how I could continue to bring photography into Indonesian fine art.

Some of my experimental ideas, I would write down on paper, and I would send for some residency applications. Lucky me again, some of them loved my kind of story. So in the beginning I got a scholarship grant from a Contemporary Museum in South Korea to do an art residency programme for one year, to spread my scanner knowledge in Korea. We call it now scanography. I chose Korea because in 2005 they were really rich and they were making many types of print. I proposed my ideas of how to make a big, good quality print with scanography. During that year, I made many big prints and researched the pixel, the resulting quality from the scanner.

I am still thinking about how the photograph can become part of the fine art market. It is about the packaging. I always make two editions of my artwork – one light box edition, and one print on paper. And now I am trying to use a sticker format. After I scan the object, I edit the images. Very good quality images, high resolution.

MC: Your compositions are very interesting. How do you decide on the way each work is put together?

AP: It is because my design training has really influenced me to make something weird. I love to make juxtapositions.

MC: You are taking very everyday, normal objects and putting them into these unexpected compositions. This one is of the traditional street food from Jogja, yes?

AP: Yes, they’ve been making it since a long time ago, and they still make it now. And I added the plastic toys to relate it to this present time. The title is ‘Food Traffic’. I love to use everyday material to bring it back to the people, with different kinds of compositions and visuals.

MC: You are playing with the idea of tradition and modernity. And a lot of your work has a lot of humour in it, a lightness which is refreshing. I’m interested in what you said before about how photography in Indonesia is preoccupied with beauty. How do you approach that environment?

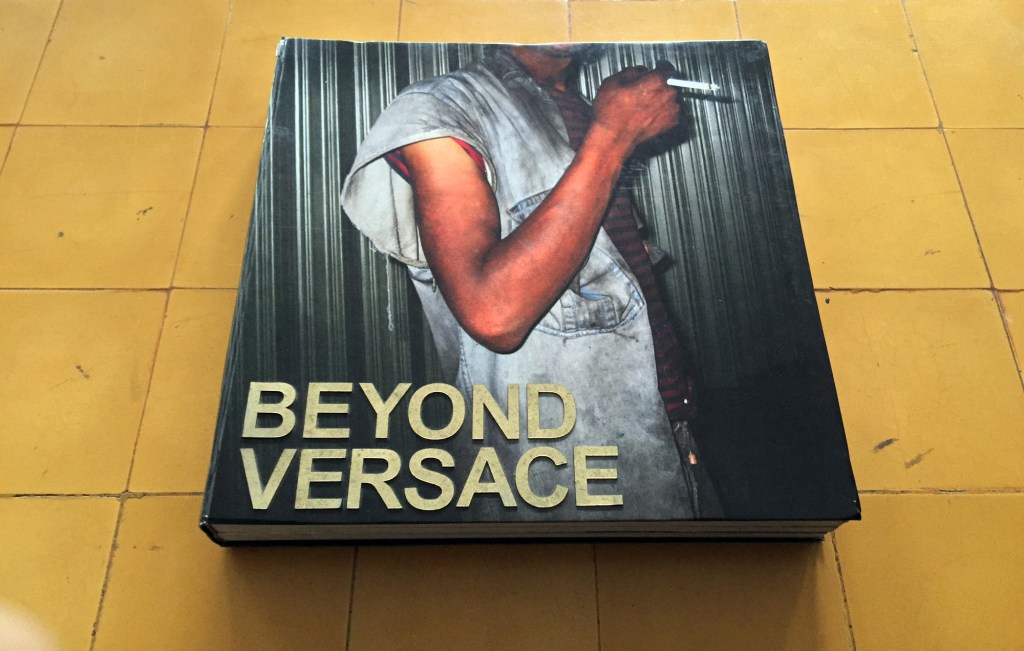

AP: Beauty is important, but I think I’m done with that. I don’t need to follow that kind of culture – I make my own culture. I will show you some of my old photographs. Since 2004 to 2010, I took photographs of people with mental illnesses in the city of Jogja. I found the important title, ‘Beyond Versace’. I was using a compact, small camera, but good quality – a Canon camera.

MC: In these pictures you can see there is a lot of respect for the people you are photographing.

AP: I’m very close to them, yes. I wanted to show that visually. In 2004, the new technique with the digital camera was Macro – the extreme close-up. I wanted to try that kind of function. So, this is my opposition to beauty in conventional photography. It may not seem beautiful for most people, but for me this is super beautiful. These people, they are models, and the city is a catwalk. I am their photographer. I was never looking for these people, but we would always meet, in a usual way.

This book is very special. This is one of my masterpieces – I use the book as a frame. I never printed all these pictures for hanging on the wall. It is more intimate.

MC: You seem to be interested in highlighting the things in our lives that are always around us but we never see. For example, the everyday objects you see on the street, or these people who slip under the radar. You are not photographing the big spectacles. This is interesting to me as someone visiting Indonesia as a tourist, as we are so focused on the spectacular sights – the Borobudur temple, the mountains, the palaces.

AP: I want to become a tourist in my own city. I have been here a long time, but I am always finding new things to see. One of the important things I have used is Lonely Planet – a very famous book for tourists. I saw Jogja from that book and I saw just the classical beauty. But it is not the real city. I love journalists, because they explain the moment as it is. Sometimes it is very sad, but it is the different perspective that is important.

MC: Do you think that it is important for the photographer to have a conversation with the subject?

AP: I think it is not necessary, but it is more beautiful if the photographer is part of the story. For me, I live in Jogja, but I did not know about all of these people. I am not a friend of all of them. But I love the situation of being surrounded with them. They are really unique. A lot of people have told me that I’m crazy – of course I’m crazy! But I need people to look Beyond Versace.

In two dimensions, you only feel two feelings. But in reality, I felt a lot of different dimensions – smell, noise, movement, attitude – which was so beautiful. Then I capture the one moment. Some of these people, they were really artists themselves. They made installations, and designed clothing.

MC: It is interesting that you yourself are a character in your stories. Your own presence is very clear here, and also in the work ‘Happy Birthday Holy Day’ since it is so personal to your history. I would like to go back to what you said about how the brain is a camera, and about how this is a collection of your memories. Could you explain further?

AP: I want to explain it to you, but it’s really just about my spontaneity. I am really bad at remembering text. Lyrics, even, are difficult. But images are easy for me. That is why I really fell in love and married with photography. Photographs can keep my memories clear as a visual, as something easy for me to remember. To remember the story behind it all.

MC: The chaotic composition of ‘Happy Birthday Holy Day’ is very interesting.

AP: Instinct is very important to me to explain my personal memory and personal feelings in a visual way. I think my brain and my attitude is like a painter, making things spontaneously. So, it is sometimes chaotic. The longer I stay, the more material I can get for my story.

MC: You are not pre-planning the works with a story already in mind – you are translating information from the outside world into visual images.

AP: With this one, the story comes from this object in the centre. This was the first sign of my first baby – a pregnancy test. If you have the two lines, it means you are pregnant. My first baby failed, he died after three months. But the technology allows me to keep the memory of this moment, this sign, and I scanned it as my legacy. I scanned this one object, and then left and right, I chose objects from my table which follows the story. All the objects are the same size as the pregnancy test. Otherwise, I chose them very spontaneously. For me and my wife, this was really sad, but this way I get to keep the memory.

MC: I like how you call this your legacy. It is a very intimate portrait of you. You get a real sense of your personality and your life story through these objects. At the same time, each object is so mundane.

AP: I think a good photograph is a moment related with other people. Objects which can be relatable to anyone.

MC: Where do you see your practice going in the future? Will you continue to experiment with scanography?

AP: I will keep my photographs going. The big concept in my brain is photography – the scanography is part of the experimentation towards my photography idea. Without photographs, I cannot do anything.

MC: I can see recently that you have been creating a series of detailed images of flowers.

AP: Flower-power! Because flowers connect everything. Flowers for birds, for love, for people who die. It is very universal. I printed some of these, because I wanted to experiment with how to display them.

MC: Do you feel that your work has any connection to cultural tradition? These flower works make me immediately think about Indonesia, where flowers are everywhere and a central part of every cultural celebration and religion and so on.

AP: I think so. My culture is represented in front of me, directly, every day. Even if I don’t go outside, it is on Instagram. It’s kind of like my energy inspiring me to keep my artistic talent accessible. Because I am not a young artist anymore, I am an established artist. Young people still want to learn with me how to produce ‘the new thing’. That’s good for me, to still practice. I feel that is tradition. I love tradition because Indonesia is full of tradition. There is no choice for me but to grab some of it and put it into my artwork.

MC: Your focus on the everyday shows how tradition here in Indonesia is not something separate and distinct from real life. It is part of the everyday life.

AP: I want to show you these artworks which I made when I was in jail. I was there for one year because of marijuana. I was able to create work when I was in jail because I could explain my language and purpose to the important officers to support my time. I introduce my tools – my scanner, my computer – and I promised to bring other inmates to become part of my project in the name of the prison. They put me in a special narcotic jail in Jogja, and I had an office, but I had to always go back to my room I shared with seven people. I collected artworks made by other inmates, as part of my research. I set up a space to become a small gallery inside the prison, and hung up the inmates’ work – the Interior Art Movement. The inmates were happy because I had another perspective on art. Of course, they were already painting and drawing, but to have a studio in the jail was impossible. It was my lucky time. From there, I built the prison art programmes, which are still going on.

This artwork is all stuff I collected from the jail, and then scanned. This is pieces of food packages, rubber bands, toothbrushes. I stole the brushes from my friend’s bathrooms. Look at how old the brushes look! It’s kind of like a portrait of a person, Indonesian-style. That was exhibited in Saatchi Gallery.

This is another of my old artworks. I took a picture in front of old TVs for four years, and I made a lightbox installation. In this one I collected Indonesian money, a low-value currency. A thousand rupiah note, and I asked people to write their stories on them. Then I scanned them. This one was from my artist residency in Japan, where I am using food packaging as a frame. In a flea market in Japan, I found these old photos, and I put it together with the packaging to make a story from the past up to the digital. I have no relation to Japanese people. But Japan is part of our history – they occupied Indonesia for three and a half years. And other Asian countries have other stories about Japan. So for me, images of Japan are very common – the soldier, the samurai. But that day, when I found the real photo from Japan, I wanted to put it together with my story of Japan. Fact and fiction. Like a samurai sword going through a chili.

In 2002, I was invited by the British council to take part in a project about contemporary Muslim identity in Indonesia. I made this installation where any girl can put her face inside – with hijab, without hijab, with burka, and contemporary hijab. I also included a CD, where people could listen to why each girl decided to wear the fashions of hijab. This girl was wearing a hijab before, and then she took it off and changed religion – it’s a long story from her. In 2002, hijab was becoming pro and contra in Indonesia. Now it has become uniform everywhere.

MC: I’d like to ask you my final question. Can you give me three names of artists you know whose work inspires you?

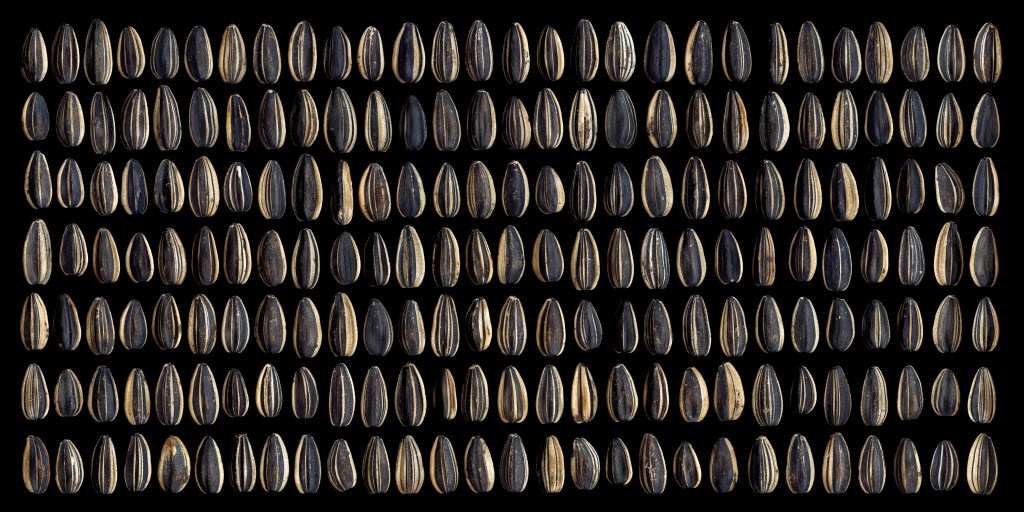

AP: Andy Warhol, of course. Affandi – he was one of the first contemporary Indonesian painters, one of the maestros. I do not use the same techniques as him, but I love the story of his life and how he became an artist. Then, Ai Weiwei. He is strong in everything – photography, video, everything. Like Andy Warhol, but in the Chinese fashion. I have a work where I scanned the sunflower seeds I found in prison, like Ai Weiwei’s sunflower seed work in London. I scanned them one by one and put them together. Doing that, I could feel how Ai Weiwei made his work.

Leave a comment