MC: I would like to start by asking you where you began as an artist. When did you first start to consider yourself an artist?

WAB: When I entered the photography department at university – at that time I was still not sure. I was just avoiding going to normal college. I liked to make drawings and paintings, and I studied interior design before entering the photography department, as a diploma. That was where I met the first year of the MES boys. They graduated from the graphic department from the same school. When I looked for a dorm, the staff recommended me to go there because there were a lot of alumni and students. There, I met a photography student, and I suddenly saw, oh! Photography can be art! I was then interested, and I went to the photography department.

The MES boys community then became very active. I was the youngest one in the group, and I started to experiment with my photographs, and they invited me to join in with an exhibition outside of Jogja, in Jakarta. Jakarta was considered an international city, with lots of media there. We got a lot of media coverage for our exhibition because it was controversial.

MC: What made it controversial?

WAB: Because it was not documentary or photojournalism. It’s art, not traditional photography, because we would cut out the negative, or put chemicals, and lots of other experiments. There were lots of comments and criticism, but also a lot of good responses from the media. I felt I had to continue this, to keep going.

MC: I’m interested in that quick change you made between traditional drawing and painting, to photography. What is it about photography which interests you so much? Why did you choose that as the most efficient or successful medium to express your ideas?

WAB: Before I simply didn’t realise that you could make art with this medium. At the time, it was not conventional. Work considered as ‘fine-art photography’ was, like, taking pictures of textures of the hair, or the human body in a specific light. Then it was called fine art. But in this group, they felt that this was not enough. This was what influenced us to become crazy, to do experimental things. We wanted more radical control. But then, after 2000, we met with other disciplines like anthropology and social science, and our approach changed. We found that straight photos were also enough. It’s more about how we see or view the world.

MC: That is the main impetus behind all of your work – the idea of how you see the world. Your practice is very broad, covering lots of topics – history, politics, faith, and so on. You are always trying to make the viewer double-think themselves. I was wondering if you could talk a bit more about some of the techniques you use to do that.

WAB: My approach, over fifteen or twenty years, is not specific or sophisticated. Effortless, even! But I like to experiment with participation and staging, and I would use props and also montage.

MC: I’m thinking specifically about your work ‘Put Yourself in My Shoes’. To describe it, it’s photos of typical tourism hotspots around Bali, and there’s a horse with pink hair placed in the middle of each scene. There’s one where the horse is just coming off the plane. It’s the journey that a tourist might go through when they’re going to visit all these traditional cultural places. Speaking as someone who has just done that exact journey as a tourist, that piece of work made me think a lot about my own positioning. Could you talk me through your thought process behind making this work?

WAB: I met the horse on Mount Bromo. There are many horses there to attract tourists. They can ride the horse instead of walking up to the top of the mountain. Horses are common around the region, always depicted as heroic or a representation of masculinity. But I saw this horse and it had pink hair and looked cute and quirky. There are also green and blue and yellow horses. But when I was taking photos, this pink one started to pose in front of me.

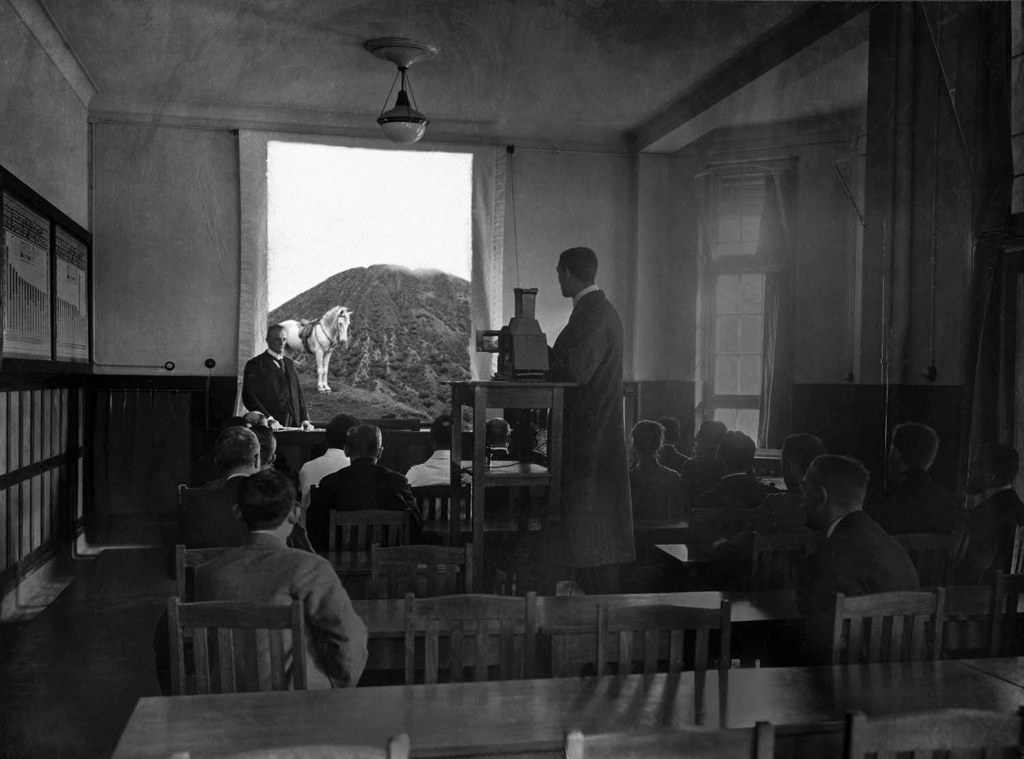

I cannot totally tell the process of this work, because it will lose its meaning. But I just kept photographing this horse, and at the same time I was going to other cities and other places. I montaged the horse into these different environments. For example, the one you mentioned in the airport in Bali: I actually wanted to document the US airplane that parked there during the G20 summit, behind the tunnel between the plane and the airport. You can see the plane in the background of the photo. After I got the horse image as an asset, I just put it in there. Also, I have a collection of colonial photographs, photos about Mount Bromo, and they had a horse on it. I added my horse in there too. I also had colonial photographs of a classroom lecture, and I put the horse as the image on the screen at the front of the class. A subject to analyse – why is this horse there?

I used the title ‘An Invitation to Put Yourself in My Shoes’ to connect with the audience. I want to invite them be this horse in its mindful state. I put it in a situation which is unexpected. The idea is that, in Javanese, we have the condition – we accept anything. When unexpected things happen in your life, you have to accept it. We call it nerimo, and it also means patience, where the cognitive and affective blend together. Mindfulness, also. I want to invite the audience to engage with these situations in this way.

MC: That work is so effective. It works on two levels. On the surface of it, it makes you think about more socio-economic or political connotations: tourism, colonial history, climate change, and what is happening in Bali, especially. But at the base of it, you have this idea of the unexpected. That is essentially what this is a picture of – a juxtaposition of surreal things together. It’s kind of like you’re inviting us to take this mindful, patient attitude when approaching these difficult political topics. I do think of your work as political. How do you feel about that label?

WAB: I don’t mind, because although we are not directly involved with political practice – political practice in Indonesia means you are going into the party as a partisan – but actually, everything is political. When you see this, as you say, there are layers of colonialism, tourism, human exploitation. Even me – I am exploiting this horse. Sorry! But I also want to address the way we connect with non-human agencies.

MC: I do notice that in your work a lot, that you use non-human subjects to replace what would be a human figure. Even just the idea of removing something and replacing it with something else or leaving a blank space – this idea that there should be a body, of a missing presence. I was thinking about that in terms of history, particularly colonial history, in that we often hear just one dominant story whilst there many others that have been lost. You put a focus on that by presenting an absence, or stand-in.

I am interested in these works that you are doing using stones with words on them. There’s one which is a boulder with the word ‘natural’ carved on it, another with the word ‘morality’. How did these works come about?

WAB: The idea was that, in 2010, there was a big eruption of the Merapi volcano. Usually, when such natural phenomena happen, I like to capture and document the situation. I am driven by these things. I met some people who started shouting at the stones. There were huge stones from the eruption pushed by the water from the river into Jogja, and people started shouting look! The stone is as big as a Kijang! Kijang is a Japanese car, and it also means deer. Then I realised that, for example, when you don’t have money or feel hungry, people will say ‘you can eat the stone’. Or when you are stubborn, they say that you are like a stone. Stones are natural things, they are innocent, but people put meanings onto them. So, I started to explore these meanings that are being put on stones. I started with the materiality, the characters of the stones. In the project, I put some real, big stones, and also made some model stones out of fibreglass into the gallery. Then I started to add words which people normal use to describe art – fake, copy, original. And I put wheels on them so that people in the exhibition could mix and match the stones.

MC: It’s a unique aspect of your work, the way you combine an installation of a thing, in an exhibition, with a photo of that thing.

WAB: It’s also similar to the exhibition with the horse. In the first work is a painting of a pair of shoes, like horses’ hooves with pink laces. In the next work, it has the character from the Netflix series Bojak Horseman. The universe of Bojak Horseman is all animated animals that wear clothes and can talk, but there’s also humans in it. In this second work, I painted Bojak Horseman in a gallery looking at the painting of the horse-hoof shoes. The scenery of the painting just like the corner of the exhibition space, so views can visit the exhibition and look at the painting just like the character. In the background you have two people crawling on the floor – horsing around! This one is realistic, where this is more cartoon. Then we have the photographs of the horse in the tourist spots. Then also there are two animations. I want to investigate the medium itself. When you see animations of flying horses or flying crocodiles, you do not complain or ask questions. But when there is a realistic photograph of a horse in an airport, we have lots of questions – is it photoshop, is it not?

MC: Again, in every work, you are subverting our expectations of different mediums. But I also really like how, with both the stone and the horse, you are going through every possible connotation of that object. It’s like you put the word ‘horse’ in the middle, and all the different meanings are like a spider-graph coming out if it – that’s the experience of your exhibitions. It’s really challenging the idea of a fixed narrative. You’re kind of exploding the object (or thing, or person) into all its constituent parts.

WAB: In the stones project, I made two stones which you could look inside, through peepholes. Inside there were two videos. The left video was footage of an Islamic group throwing stones. There is an Islamic group called Ahmadiyya, they are considered not Muslim by the Muslim majority, who are stoning them. Then the video on the right is footage of Martin Scorsese’s ‘Passion of Christ’ where Mary Magdalene was about to be stoned, and Jesus says if you don’t have a sin, you can throw the first stone. And nobody throws any because they are all sinners.

In the next work I used small real stones with the word ‘morality’ and put them on my back. Then I did push-ups, and when I went up the camera focuses on the word and when I go down you can’t see it. I did that until I got tired. There was also a video of me in the water, with a stone with the word ‘necessity’ on it. And there is somebody floating with a fake stone, because sometimes a big stone can be a necessity when you’re in the middle of the ocean! I just want to stress out this situation.

MC: You’re always challenging any singular, monolithic idea, whether that’s any singular idea of what faith is, or what art is, or morality. Instead of these stones dragging you down to the bottom of the ocean, they keep you afloat, unexpectedly.

WAB: To go back to the topic of art – at that time there was a big issue in the art market, because one of the big senior collectors opened his collection and private museum, and some people recognised that there were some fake paintings by Indonesian maestros. Someone from the media asked me what I thought about these collector issues – I couldn’t say anything, because he is my neighbour! I don’t know whether it is fake or not.

MC: I’d like to ask you more generally what you feel about the art world, since themes surrounding the art world’s bureaucracy appears in your work a lot. But regarding the fakes – it is very interesting in terms of the history of art, since there is this art historical idea that an original work of art has a unique aura, coming from the primacy of the artist. But then, in your work you are of course the master, but you are drawing from all sorts of sources – Bojak Horseman, Martin Scorsese, all these layers of references. You are separating each element from its original aura in an interesting way. So the idea of a fake masterpiece is kind of anachronistic in this context.

WAB: After a while, even the fake become original. I was raised during the explosion of postmodernism, so I don’t care about originality. Even though postmodern thinking is probably not good, in the end, I still carry it with me.

MC: I am thinking of a particular work of yours which was of an exhibition space. You had edited out all of the actual artworks from the image, leaving just white, blank space where the sculpture would have been. In light of this work, I’d like to ask you your opinion on the art world.

WAB: At the time I was feeling very bored about how people always focus on the works, and never focus on the spectators or the viewers. They are also part of the infrastructure, no? I wanted to highlight this element of the art world infrastructure – the supports. Without viewers, there would be no artwork!

MC: That’s another postmodern conversation – if art is in a room where no-one ever sees it, does it exist? What techniques do you use to bring the spectator into the room?

WAB: It is very complicated as a question, and also to answer. I could answer in Bahasa Indonesian more smoothly than I can in English, but I will try to describe my process. I am a gallerist, because I have this space at Ruang MES-56, and sometimes I become an artist, and sometimes I become an art manager, or gallery visitor, or curator. At the time when we started to use the space to show our work, I felt that we had to defend this medium, to give it an equal position with other art forms like painting or sculpture. That’s why we had the space, and we had friends with the same vision. We had the space, we had the works, but nobody came. You know the feeling. Subsequently, I focused on the visitors, because between the artwork and the viewer there is something reciprocal. The viewer activates it.

In 2013, I had a project here in Ruang MES 56. Our collective had a group show in a commercial gallery, where we hoped we would sell works. But the works did not sell. All the crates came back here and occupied our small space. So, I made a project with them. I displayed the crates with the unsold works inside, and some of the works still wrapped in bubble-wrap I hung on the wall. I had some photographs which said ‘do not fold’, and I folded them and installed them. I had some videos with the crates and a frame on its side with a hole in it, with flies inside the hole and flying around it. Then I put on a closing ceremony after one month. I invited a performer called Naomi to work with the Situationist International manifesto. She cut up the manifesto very small, and during the ceremony she shouted the manifesto and gave the pieces away. Also, I told the guests that, if they saw a light flash, they had to freeze for five seconds. I recorded all of this. Some people started playing music with the crates, and some people took the works outside of the gallery.

MC: That is so fascinating. It’s exploring what art is in the context of gallery rituals, institutional rituals. But the fact that it was your actual artwork inside the crates adds an extra layer. Where does the meaning of art lie here? Is it with the unseen artworks, with the crates, with the audience? I don’t think there is an answer.

WAB: What my friends considered to be just things – they became art after that. Even before this, I would always invite people to take part in my work. For example, I have these plastic fangs and I would take people’s portraits wearing the plastic fangs. During this time I was a bit of an introvert, but this motivated me to talk to people. I was really interested in the relational aesthetic.

MC: I would like to ask you about the experience of working in an artist collective, especially in the context of Jogja. How important is the collective experience to your practice?

WAB: In my own personal context, as I already mentioned, we were all photography students and we all wanted to become artists. Now, I think I am a bit bored. I am still part of the collective, I am still contributing, I am still thinking about it – but now more and more I feel I have to give a space for the younger generation in the collective. Otherwise, as is our culture here, elder people will have all the control. I don’t want to be like that, because the younger artists will only listen and not make things for themselves. I realise this situation, so I allow them space to do whatever they want. Collectivity is important, I think, if you want to make a movement, to do something together. But there are also the negatives, especially in MES, where all the members are boys, all individual artists who have their own ego.

MC: It really is playing into this history of manifestos, where it is important for creating change – revolution – but also when you write down your aims, you are placing a limit on yourself. Placing parameters on what you can be. So I think it’s good that you are allowing this place to become fluid, existing beyond yourself.

WAB: Somehow, I think, either I don’t like or don’t engage with the younger generation. They are more engaged with their time – with TikTok, with new trends, new music – whilst for me, I don’t engage with this new phenomena. I want MES 56 to always be relevant for its time, and I feel that probably it is not my time anymore. It is the time for the new generation.

Our collective before was more homogenous – only photographers or artists who work with photography. For me, now, I would love there to be a collective with many different disciplines. Actually, for the Sharjah Beinalle, I will be working with a researcher, an architect, a writer and a performer. Not as a collective, but our project name is ‘the activism archive’.

MC: I will keep an eye out! I will ask you my final question, which is to ask you for three names of artists who inspire you, or who have an accordance with your work.

WAB: Sigit Pius. He is now less active as an artist, although he has a work in ArtJog. Then also Agus Suwage. And Melati Suryodarmo, the lady performance artists, of course.

Leave a comment