MC: I would like to start by asking you when you first became an artist, and how did you first get into art?

YP: Maybe from my father, directly from daily life. My father worked in the ceramic industry. He was a ceramic researcher, but not in the art sense – more historical ceramics. He worked in Bandung, and he also had a hobby of carpentry, woodworking and building interesting things. My father lived in the back of the office, and I was often around the ceramics studio and felt that, someday, I want to make work like this. But I didn’t know what art was yet. In high-school, I received information about art. I researched, and I discovered the Institute of Technology in Bandung, and ISI in Yogyakarta. I chose to study in ISI, although I had never done any specific studies of art before. My major was sculpture.

MC: Why were you so drawn to sculpture?

YP: Because I am interested in medium. I can only explore all of this interest through sculpture. I can study monuments, materials, space. I am interested in interior design, architecture also – I am not interested in making illusions, like a painting. Of course, from my generation, there are only two artists still working in sculpture: Yusra Martunus, and myself. Because it is very difficult for sculpture to survive. In Indonesia, the price of sculpture is lower than painting, but the cost of production is higher. Sometimes before I worked as a professional artist, I had side-jobs working in restoration.

MC: After you finished studying, how did your work develop?

YP: Before my generation, there was a struggle to create a conventional form of sculpture: you must always use high-quality material like metal or stone, very conventional. I tried to change this. I used rubber and plastic, stuff like that. My teacher always asked me why I used these materials – these are not part of sculpture studies! But for me, material is very important as it connects to the identity of the sculpture. If I am making it weak, I will use rubber; if I am making it strong, I will use metal. That’s important.

MC: Going back to the idea of illusion – you are not trying to make a weak material seem strong, or a strong material look weak. You’re not trying to override the inbuilt, formal qualities of a material, messing with perception.

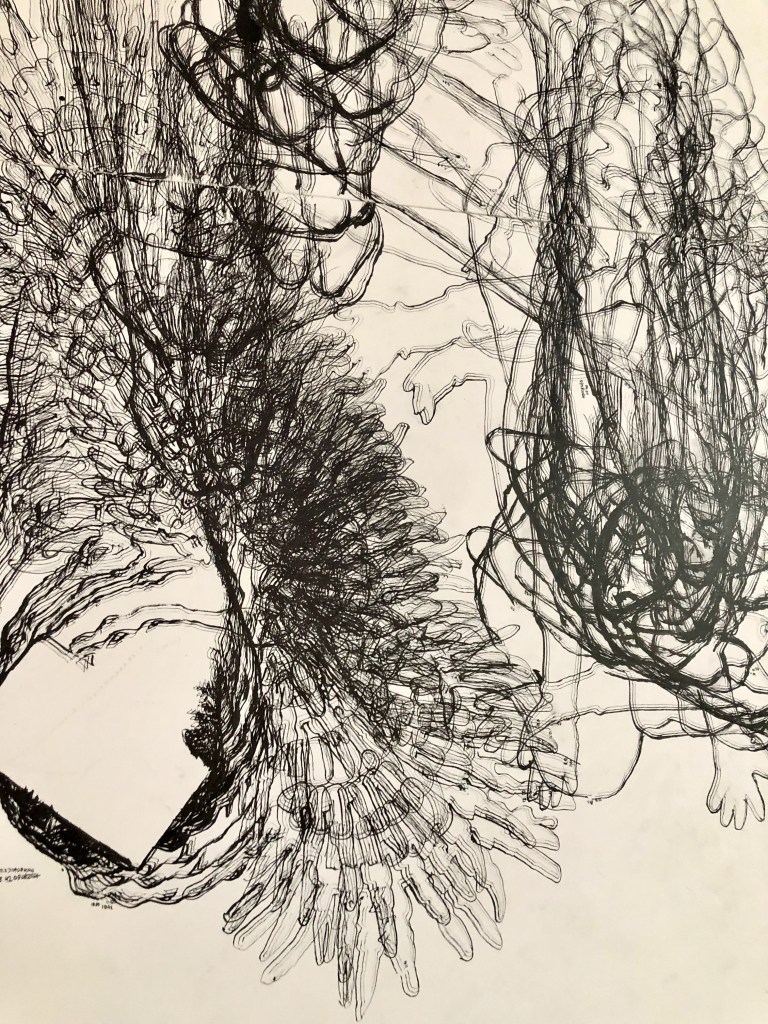

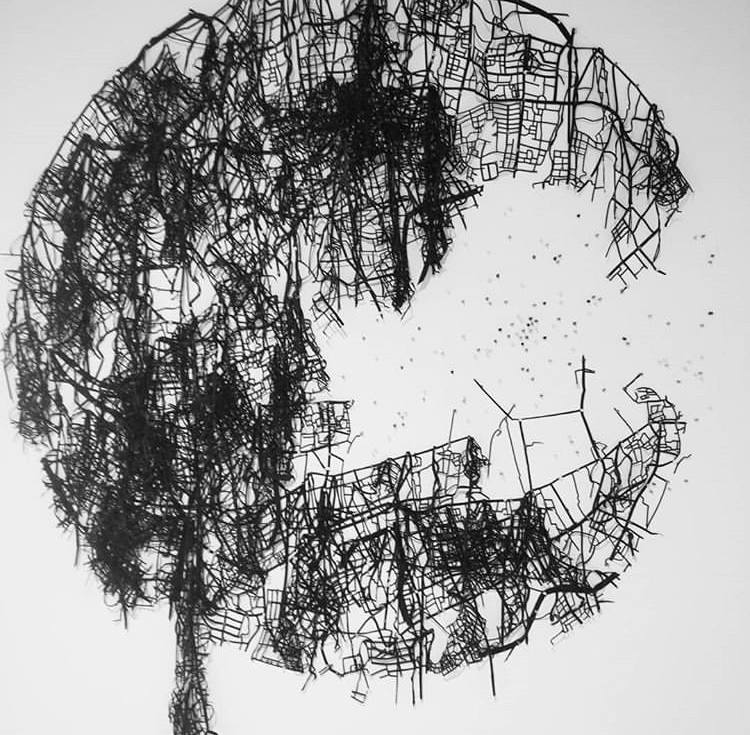

YP: I feel that illusion is not effective. I allow the material to be itself. Like in the ‘Rekam Shadow’ series, people always think about painting. But for me, this is not a painting – I wanted to document time and space specifically.

MC: Could you describe how you create the works in this series?

YP: Starting three years ago, my collective with Handiwirman Saputra, M, Irfan, P. Sancoko – the Jalan Pulang Collective – we were thinking about the base of art. Ok, line. But the meaning of line is not just the start of a study. Before, I never used the canvas or any flat media, but for line I felt that I should change my perception of it. I wanted to use line to show the process of documentation in an artwork. So I take some object which I own or which I have made, and I put it on the canvas on the ground. I do this in different locations – sometimes here, sometimes outside – from 8am to 4pm. Over the day, I draw a line around the shadow of the object on the canvas.

MC: The effect is very interesting, as you are tracking an object’s existence over a period of time. There are multiple lines, all roughly depicting the shape of the object, but each slightly different.

YP: Because my background is sculpture, I think I am usually part of the documentation process when I make art. Here, I could put the canvas at maybe 45 degrees, and it would be a very different result. But I only want to show documentation for this specific place and specific time – not my own actions.

MC: I’d like to ask you more about the idea of documentation. Often, in the art world, it’s an argument whether an artwork which has a limited time-scale, such as a performance, can be considered to exist if it hasn’t been recorded. For example, if someone does a performance which is over in an hour, and no-one videos it, can it continue to exist? How do you feel about that idea?

YP: I have not thought before about performance, but my friend is a performer and he took part in my artwork. But I am not really interested in the performance, I am only interested in process. Because I think about meditation, things like that. You can continue a line, or you finish a line. But it is about your body, controlling your body. So my work is about organising the body in this way in relation to the sun.

MC: So the only things you can control in this situation is your own body, and everything else is out of your control.

YP: Last time I made this work for the Indonesia Batutur, I used two performers – one artisan dancer and one person from theatre. So I put them in the space and I drew around their shadow. At 1pm, the dancer fainted! I told them before, if you cannot freeze in one position, you can change – you can sit, or sleep. But not fast, just slowly. After that, they would only sit on the canvas! I copied the shadow.

MC: What is the difference between drawing around a person’s shadow to drawing around an object? I suppose it is an interesting relationship between the body, the self, and these powerful outside elements which don’t care about you.

YP: Everybody is different about themselves. Like maybe for you, here, this weather is hot, but for me it is ok. It is the same thing with the artwork. I try it with different people. But I am exploring how the different generations think about the power of the body, about how the body fights and fails. I say that if you are focused on the line, you are hypnotised – you can relax, you can feel in your body that everything is ok.

MC: So you have boiled down the elements of art to line, duration and space…

YP: The interesting thing about these documentations is that they cannot be repeated. You can go again to the same place, but the sun position will be different. The earth moves, the sun moves. This is the definition of detailed documentation – specific for time and specific for place. Plus, for this artwork, I tried to show the movement of time. If you use a static light like a lamp, you make a line that is static. But here the shadow, the line, is always moving to another place.

MC: So what you’re really recording is not the object or the person, but the movement of the earth though space.

YP: The object for me is only a prop to help me to make the work. A compositional prop.

MC: This idea that objects are only props – does this translate into your sculptures? The works in your studio use a lot of ready-made objects, such as ceramic plates. How do you feel about objects in that context?

YP: I am interested in objects, particularly antique objects, because they tell a story about the old generation. For example, the design of the chair – Indonesia has a specific chair. This one here is not perfect, but it is important because it is made in one piece and cannot be replicated like in a factory.

I think that the object can’t lie, not like historical telling. History can be made on request for certain people or governments, for a specific function. But the object cannot lie – if you know this chair, you can read real history in this chair.

MC: That’s fascinating – the object is the only thing that can tell the truth about time. In this work here, you have the chair – a motif which appears again and again in your work.

YP: I have a series I call the Artkeolog series (referring to artistic work and archaeologist work), which is all about the broken objects I found in the homes of people. I would ask them if they had furniture or something like that in a broken condition, and I would buy it and restore it, but would put a new meaning in it. I would put my own opinion in it. In the studio, I made the Chinese peranakan chair. The Peranakan people are Southern Chinese people who settled in Indonesia and other places in Southeast Asia. Peranakan chairs have a specific form of symmetry, and rules that it must have only a very formal, straight position. I changed this, because I only bought one portion of the chair, the seat part. So I changed the top so that it slanted towards the left. It is all about the Communist party in China after 1956. The Communist party put fear into the people. It was very traumatic. They changed the houses and painted over the windows and doors. The Chinese Peranakan people traditionally create a good surface for the doors and windows, with jewels and gold leaf. The Communists changed it to cheap paint.

The Communist party never opened the door of China and would never go to their neighbour. Only the personnel of Suharto could connect China with Indonesia, for business purposes. Later, the issue for the Indonesian people was the PKI – Party Communism Indonesia. The PKI started from the Chinese. Chinese people in Indonesia were very scared about that era, because of memories of the Suharto era and what had happened with the Chinese Communists. Before, in Indonesia, China was the hero of Indonesia. After the Suharto era, you can never find any Chinese hero in any book studies.

So the back of the Peranakan chair is leaning to the left. If I see you sit in my chair, you look like you are on the right. But if I sit in the chair, I feel myself leaning to the left. Because in Indonesia, the Party Communists, the PCI, say that Communism is to their left. I parody this with the chair.

MC: That’s fascinating. I went to the Yogyakarta museum yesterday, and I noticed how every object of piece of furniture that would traditionally be found in a Javanese house have a deep cosmological meaning. Even to go back to Buddhist theory – all objects are designed to reflect this belief system in even the smallest way. You are playing with this, saying the object is not just an object, it is a model of something much bigger. Everything is representative, these everyday objects representing huge things like the turning of the earth, or a powerful political regime.

YP: Maybe in Asia, we have connections between the cultures. We trade with the Chinese, and this can sometimes change the culture: motifs, ceramics, furniture, silk. But if you want to understand the Javanese, you can go to Bali. Javanese people love Bali, and see the Baduy people there as a role model for daily life. You can go into the Baduy village – they do not use electricity, camera, phone connections, or TV. They never buy anything from the outside, they only get food from the area.

MC: Do you think that tradition is important?

YP: Yes, it is important. I think the generation before us was the last to maintain life without thinking of the industrial. They thought about how to connect to the future, how to connect to their neighbouring people, how to connect to the trees and nature. They did not cut the tree for industry. If they needed a house, they would cut just one tree. But then they sold the Jati tree wood, expensive by Indonesian standards, and soon all the Jati trees in Java were gone for industry. If you want to grow a Jati tree, you must wait three generations.

MC: Industry is very short-sighted, only thinking about now. It draws a disconnect between people and the wider idea of time, of nature.

YP: My grandpa, he would never think about cutting the tree. He would think, this is for my grandson. This generation will always cut down the tree before it has time to grow strong.

MC: Do you think the future is in danger?

YP: Yes, of course. I think previous generations thought about the future, about good quality life in the future. I am interested to combine my work with local beliefs, local design, local skills, because it is important. Sometimes people say that if you want to read a history of Indonesian art, you always start with Raden Saleh. Because Raden Saleh was the first to get an education in art from the Dutch. But I think this is not correct. I think if you want the real Indonesian art history, you must go back more, to wood carvers, batik workers, ceramic makers. In my generation, the government is not caring about traditional design and culture. It is not protected. It is exploited – thinking about sales, thinking about trade. You store up all the money for yourself. But previous generations had a cleverer view of life.

MC: And you are trying to reclaim this attitude in your artwork? I would like to go back to some of the works in your studio and ask you a little more about the explorations you are doing with medium. You often take a medium and experiment with its characteristics.

YP: For me, medium is so important for my artwork because medium has history and process. It is not about skill. In study, ok, I can draw a portrait. But this is too perfect – I want more. Sometimes, my emotions can only be balanced when I choose the right material. If it is not correct for me, I do not use it. Starting in my studies at ISI, I never used sketches or maquettes for my sculptures – I only think. But I will not know beforehand how the artwork will look when it is finished, and I am happy and surprised when I see how it turns out. But now, I have exercised too much. I know what it will look like finished and I am no longer surprised. Surprise is important. Like in the shadow series, I didn’t know what the finished work would be like because it is controlled by the sun and the object’s shadow.

MC: So you want to take away your control over the process and let the medium itself guide the work?

YP: For fun! I can only continue working when I feel that surprise. Routine is like working in a company, so boring. But to change my artwork daily, I look for a big surprise every day. This is why medium is so important for me.

MC: Thank you for explaining your work to me. I’d like to ask you a bit about your work in the collective Jalan Pulang. How much does artist community and collaboration mean to you? What are the benefits for you?

YP: I can sell with my collective, with younger generations and older generations. If I am bored in the studio, I can go to my friend from the collective and see the work he is making, and I am inspired again. So, for stability and for productivity. I do not chase just one generation – I sometimes visit my friends’ studios, like Handiwirman or Sancoko, and sometimes I will go to Ace House to visit the younger collective there. I think it is important.

MC: Can you give me three names of artists like this who have particularly inspired your work?

YP: Handiwirman Saputra, M. Irfan, P. Sancoko. I am interested in Handi’s work particularly because his work has the same characteristics as mine – he explores the material, has knowledge about material. He is the same generation as me at school. I am also inspired by Agus Suwage. I live in Jogja and I can see work by senior artists no problem. This convenience cannot be found anywhere else.

Leave a comment