MC: We have already talked a little bit about your background, your art training in Melbourne and so on. But I would like to ask you if you have an ‘origin moment’ as an artist? When did you start to call yourself an artist, and what was the impetus behind this?

AG: I guess now, in my forties, I’m sure – I have to be an artist because there’s no other jobs I know how to do, so I guess I have to commit to it! I suppose the starting point was in 2005, when I was invited to participate in a show. This feeling lasted for three years, four years, five years… and then when I entered the tenth year of practicing, I was looking back like, shit! This is it. This is my job.

I was a full-time artist for maybe four or five years, and then hit a crisis. The art got a bit abandoned, and I had a family, and I was focusing on the work side of things – teaching, commissions and design-related work. Then when I hit ten years, I felt, ok, I have to do something about this. I have to start making a living out of art rather than keeping it as a side thing. Even still, I am still struggling but it is less of a struggle than it was.

MC: When you decided to work on your practice full time, did your style change at all?

AG: Yeah, when I had my full-time job the style was very different. I was teaching art to high-school kids, and there I started to realise that I had to start talking and thinking differently about certain practices. I would give them assignments and tasks based on coffee-table art techniques, and that helped to reduce my mind to just the pictorial.

MC: In a way, backtracking on the more conceptual training you had in Melbourne?

AG: Yes, that was when I started to put aside some of the conceptual, avant-garde stuff. Like, lets be humble about this, let’s not put such heavy stuff on these kids. Because it’s not art – education is ethics. I had tried to start thinking about my teaching as art – useful art, turning the art gallery into a high-school room – but it didn’t work for me. I tried, it failed. From then on, I felt like I wanted to start something from scratch. I had a new-born, and when she grew up to about three or four we started drawing together. We watched a lot of Disney, and I felt a bit brainwashed and confused. Shit, what has happened to my practice?

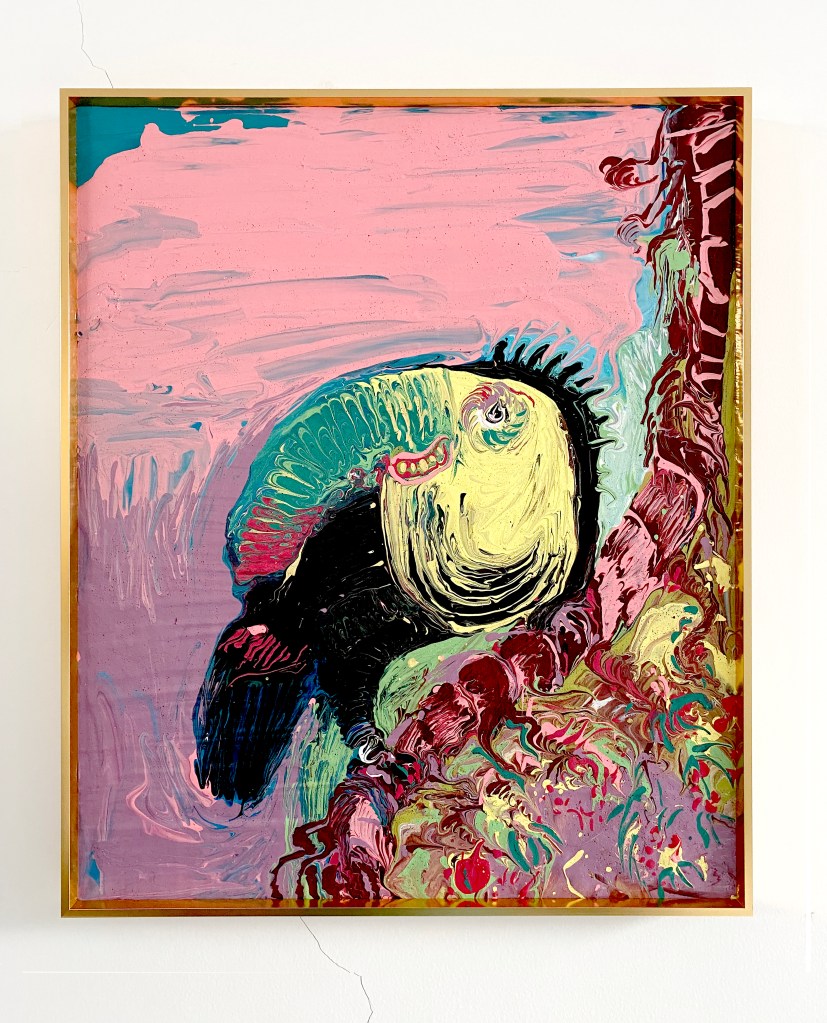

In 2014, I put out a table of all the stuff I made with my daughter, the drawings, the marks that we put on paper. I started slowly from there, trying to ‘fix’ my daughter’s paintings. Very crafty, like the kind of thing you’d see on YouTube, a cheap DIY. I was trying to transcribe her gestures and mark-making into something more professional. The difference between me and my daughter is that she doesn’t know what she’s doing, and I do. Suddenly, these zombie-looking characters started coming out of these paintings, and that was it.

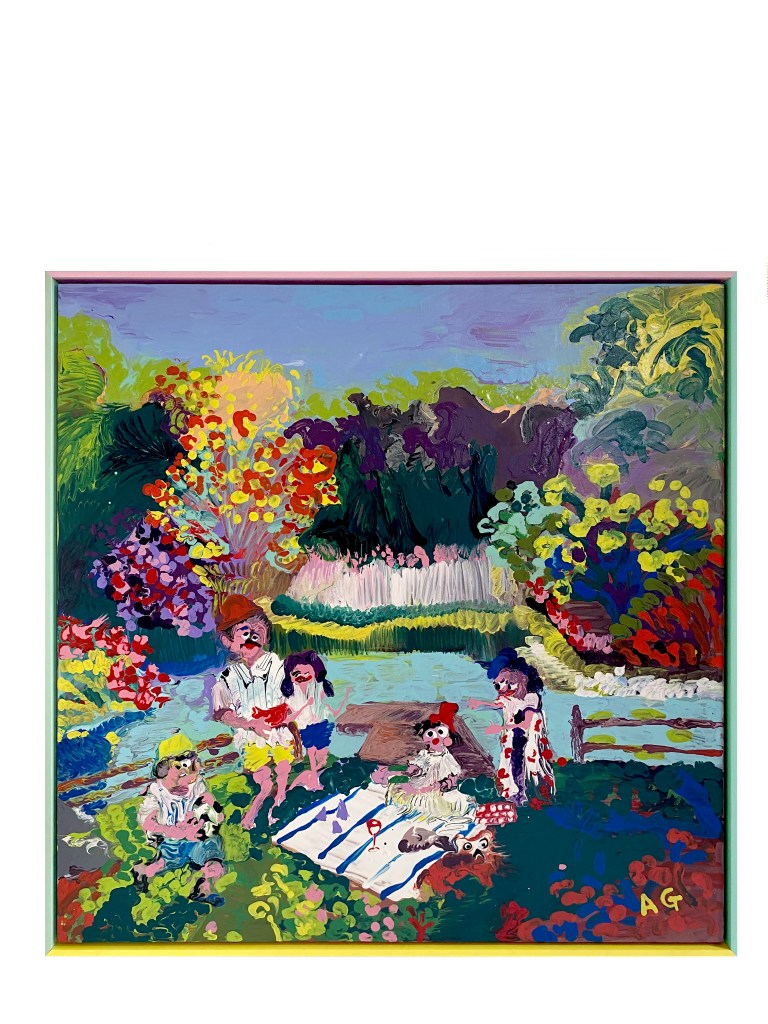

MC: To describe your paintings, you are using very, very bright colours and very thick application of paint – pouring the paint, almost. You create these figurative scenes, using narrative storytelling. Very gestural, childlike, playful. It’s an interesting conversation to have, this relationship between the conceptual, ethical mind and the childlike urge to just put marks down. How do you reconcile these two sides of your practice – the paintings versus the conceptual installations such as what you made for ArtJog?

AG: Painting is more immediate. It’s not complicated to gather the materials, you just go to an art shop, buy the canvas, mix the paint with water, put down a mark, and the day’s work is done. You can see the work you’ve done, even if it’s crap. Things like education or installation, you have this fourteen-week programme, and at the end you have a result which is either crap or good. With installation you have to work with the space, respond to the lighting, propose it to the gallery, get funding. If you need help you have to hire a builder. There’s a lot of people to meet. When I started painting, I thought ‘why didn’t I do this sooner?’ It’s an opportunity for quiet time, as well, when you go to the studio and not have to work with anyone else. You can be selfish for one day.

Teaching in high school, I started to realise that drawing and painting is older, it’s the most accessible tool, it’s always been there. You don’t need to be smart about it. I guess we need to rehabilitate this idea that painting is accessible – I know there is a negative association with the word ‘accessible’ when it comes to the market, but I think let’s not be allergic to this kind of thing. It’s actually the world’s best friend.

MC: It’s testament to the elitism of the art-world, I suppose, that anything which is colourful, childlike and straightforward is considered a downgrade against the minimalist or conceptual.

AG: The childishness of the characters that I make is also a way of trying to put a childlike disturbance – a wedge – onto serious narratives and grand theories, whether that is climate change, colonial legacies, so on. I’m trying to understand meme cultures, the Instagram story where you put gif stickers on faces, big eyes – maybe that’s it, you know, that works. Putting that onto an existing painting from the Masters, but making it seamless. I like that painting is just a flattening of references.

MC: You can put multiple times and places onto one plane, and allow them to have a relationship with each other. I would like to ask you more about the subjects within your paintings, because they are pretty wide ranging. You’re creating narrative worlds within your paintings, using images from world politics, history, references to Impressionist paintings. What is your thought process behind these paintings?

AG: The selection of images from Pinterest or Instagram or the internet is pretty random. I try to create rules, but there is no grand narrative or theme. Every time I go to the studio I have a bunch of images that I print from the internet, and I look at the kind of canvas that I have. It’s kind of moody, based on my feeling on the day. But often it has to be images that are cliches, also. Like roles that are forbidden, men and women’s roles, domestic scenes, things that are forbidden in woke culture. Like ads which don’t exist anymore of women serving men, or ads for smoking.

MC: Why does this interest you, this idea that woke culture has deleted these images from public consciousness? Are you worried about cancel culture?

AG: It’s more just about showing things that are forbidden, and exploring why. I mean, I know why we don’t see these things anymore—because they’re pretty bad, and we don’t want to participate in these structures. But for me, it’s also about how today, we have the ability to look at the ‘unconsciousness’ of a certain time—stuff people back then didn’t even have a name for but that we now carry so many labels for (so Netflix!). We have a consciousness today where we all have lots of guilt imposed on us, and I don’t think we need any more guilt. It doesn’t invite calm. I try to resolve this in painting by mocking both sides.

MC: Morality does come up a lot in your paintings. I’m thinking of a particular painting of yours which is a picture of Putin holding a cat. It’s so child-like. If you are looking at these strange guilt-induced moral conundrums we have through the eyes of a child, you kind of realise how circular they are.

AG: I like to play with that. I want to be a stand-up comedian, with visual comedy. I’m impressed with the way certain few comedians can talk about politics – both sides – and get away with it. Also looking at the discourse of activism. I mean, whatever they do is amazing, but I’m just trying to say the same thing in a different way. An interruption of symbol or icon onto an image so that it becomes disturbed. Not just saying ‘we should stop this’ or ‘we should do this’, but make it more confusing about where one position is.

MC: This feels like a good point to ask you about the exhibition you had at Rubanah Art Space, ‘Sleazy Environmentalism’. Could you explain to me a little bit about the rationale behind that exhibition?

AG: I guess it’s about that narrative of trying to be an environmentalist, but with a twist of perversion on the mainstream environmental discourse. This is the kind of narrative which builds into my new paintings, too, even if the subjects are randomly selected from the internet. The ‘sleazy environmentalism’ work has been a long, ongoing discussion with my friend Mitha Budhyarto, who curated the show. We talked about how everyone is revisiting colonial legacies today. A lot of the languages and narratives of decolonial discussion from our side – the colonised, or ex-colonised – has only really focussed on the human and the sentimental. Maybe I’m not sensitive enough, but it has always felt sentimental, and the art which deals with colonial legacies feels overly communicative and instrumental.

MC: You mean it’s always a personal narrative of the individual, rather than a discussion of the superstructure?

AG: Yes. And we thought about whether we wanted to participate in this sentimentality within the narrative of the show. So we slept on it, and decided no! We got this book ‘Bad Environmentalism: Irony and Irreverence in the Ecological Age’ by Nicole Seymore, which had a really interesting perspective – like, let’s look at nature and the environment not as something noble, and lets instead look into the practice of ‘bad environmentalism’. Bad environmentalism – what is it? Perversion is one way to do it. Let’s sexualise nature, make it funny, make it weirder. Let’s not normalise the weirdness of nature or turn it into nobility.

MC: The actual work that you created for the exhibition are these moth-like or bird-like hybrid sculptures, kind of monstrous. Doesn’t perverting nature contradict the aims of environmentalism? Or is that what you’re trying to do?

AG: We are just trying to find a new language with which to talk about nature, and to pervert the narrative of mainstream environmentalism. Let’s not scream to fix the world, as just one person.

MC: It goes back to the guilt thing – I think guilt is not the strongest motivator for action, because it kind of immobilises you. Guilty people run out of energy quickly. Maybe a fascination or fear of nature, or even sexual curiosity for nature is a better motivator.

AG: It’s like Extinction Rebellion. What they’re doing is great, but typically their actions have failed or backfired – historically as well. Why is that? Is it because the initial mindset is already good versus evil? If you scream loud enough there is always someone or something to fight against. I want to figure out a different narrative that goes beyond this narrative of bad and good – but doing it badly, as well! I mean, I am not a perfect environmentalist myself.

MC: I don’t think anyone is. It’s like Shell or BP telling us to turn off the taps and use paper bags.

AG: Something like that – that’s sleazy environmentalism. It’s recognising that we are bad environmentalists, because it’s impossible to be a one-hundred percent good environmentalist as just one person in this society.

MC: It’s kind of the same as the ‘Bad Feminist’ argument. But I would like to perhaps talk about more about your more performance-based or conceptual pieces, particularly the work you made for ArtJog Biennale made from materials taken from artist studios.

AG: That’s an extension of my habits, the site of my practice – trying to work with limitations. Because I am limited, in terms of budget, I was always living on the edge. There was no way to buy materials, so I had to work within these limits. For ArtJog, I started using artist studio’s junk. I’m interested in curation, of course, but my work has always dealt with waste and rubbish since the very beginning. Thinking about the marginalised. Something unexpected happened when I received work from artists to exhibit. I only got four or five artists to contribute work, but the stuff they sent me looked terrible on display because it was not interesting. But then I got the scaffolding from the exhibitions, which was used as a kind of superstructure dividing the space. I saw it as art’s leftovers, and I wanted to complete the picture. So I started reconfiguring the material, responding to the trees, and put the work inside of it. It was really about seeing how far I could go within these limitations.

MC: It’s interesting to think about the artist studio as a place with waste products. It’s a production plant, in a way, with input and output like a factory. It makes a change from thinking about the artist studio as a sacred space, where material is really holy and special. Instead, it is thrown away. I know that you were influenced by the Fluxus movement – how did your academic grounding in these ideas affect your practice?

AG: My thesis was on chance and entropy, about materialism and how materials are very active and have their own agency and desires. I’m interested in shifting away from the idea of artists as the centre of meaning, instead having materials producing the meaning, or rather, triggering certain meanings. It’s not just humans imposing meaning onto materials, or matter. Materials, or matter present themselves to us. I am trying participate in the movement towards the artist as facilitator and collaborator with materials, intersecting with the social. I’ve been devising a lot of methods to create a situation where that can happen. I use a lot of chance operations, after John Cage, the roll of the dice, the throwing of coins, tarot cards… stuff like that, to determine the outcome of the work, allowing the artist to be a facilitator to the materials. Or creating rules where I can only make work using materials from within the parameters of the exhibition itself. It’s like I am getting rid of the control, around eighty percent of it, so you are left with only about twenty percent control over the outcome.

MC: Does that feel freeing for you?

AG: Back then it did, yeah! When I was in Melbourne, that method worked, somehow. Melbourne is very organised, geographically ordered. But trying to bring that here to Jakarta you realise – no, you need control. If you bring that kind of mentality here, it just comes out as mismanagement. I don’t want to reflect how the government works! I don’t want to be that kind of citizen.

MC: I also assume that materials here in Jakarta would tell you a very different story than materials in Melbourne.

AG: Yeah, you need to care for materials here, you need to look after them and clean them up. They need a different treatment, as if they are a people. It’s almost ethical – you have to make them look nice so they last longer. I guess the geography contributes to that. So I suppose the work that I do now is aesthetically more pleasing than the Melbourne work – maybe it’s because of that caring treatment. Maybe it’s also because I have a daughter now, you need more affection. Making these paintings – you get back pain over it! It’s the extra care.

I am also trying to advertise this fact. Like, let’s make a campaign about flowers, birds, sweets, and beautiful skies! All you can see in the world around you is grey and black. Going back to Impressionism, that was a time of revolution as well. The Impressionists were painting things like flowers and leaves in the pond. In some ways we see this as a form of escapism, escaping from a shitty reality. But when you think about it, Monet was never against revolution. He was creating beautiful scenes for people desperate enough to see beauty – to need beauty. It’s like the activism thing, creating a sense of hope. The reason I choose to paint beautiful stuff is mainly because of that, trying to give hope rather than trying to escape from reality. We, at least I, have a bad, guilty association with the world that we see, when it really could be a symbol of hope.

MC: My final question is to ask you for any names of other artists who you feel have an accordance with your work, who you are inspired by, or contemporaries who you really like.

AG: I love Ade Darmawan’s practice. He is one of the founders of Ruangrupa, an artists collective in Jakarta. In terms of installation, Ade Darmawan is an easy choice. In terms of the subjects of painting, I would say Zico Albaiquni.

Leave a comment