MC: We have already talked a little about how you came to the art world through musical instrument-making training. I would like to ask you specifically why you came to focus on printing?

MT: At university you get to try multiple different processes, giving you the freedom to explore. When it came to printmaking, I was really intrigued by the aesthetic. It’s always a very magical experience every time you pull the paper off the press. It’s as simple as that. I started to learn the techniques, getting a bit nerdy about it – learning about the types of paper to use, talking to the technician.

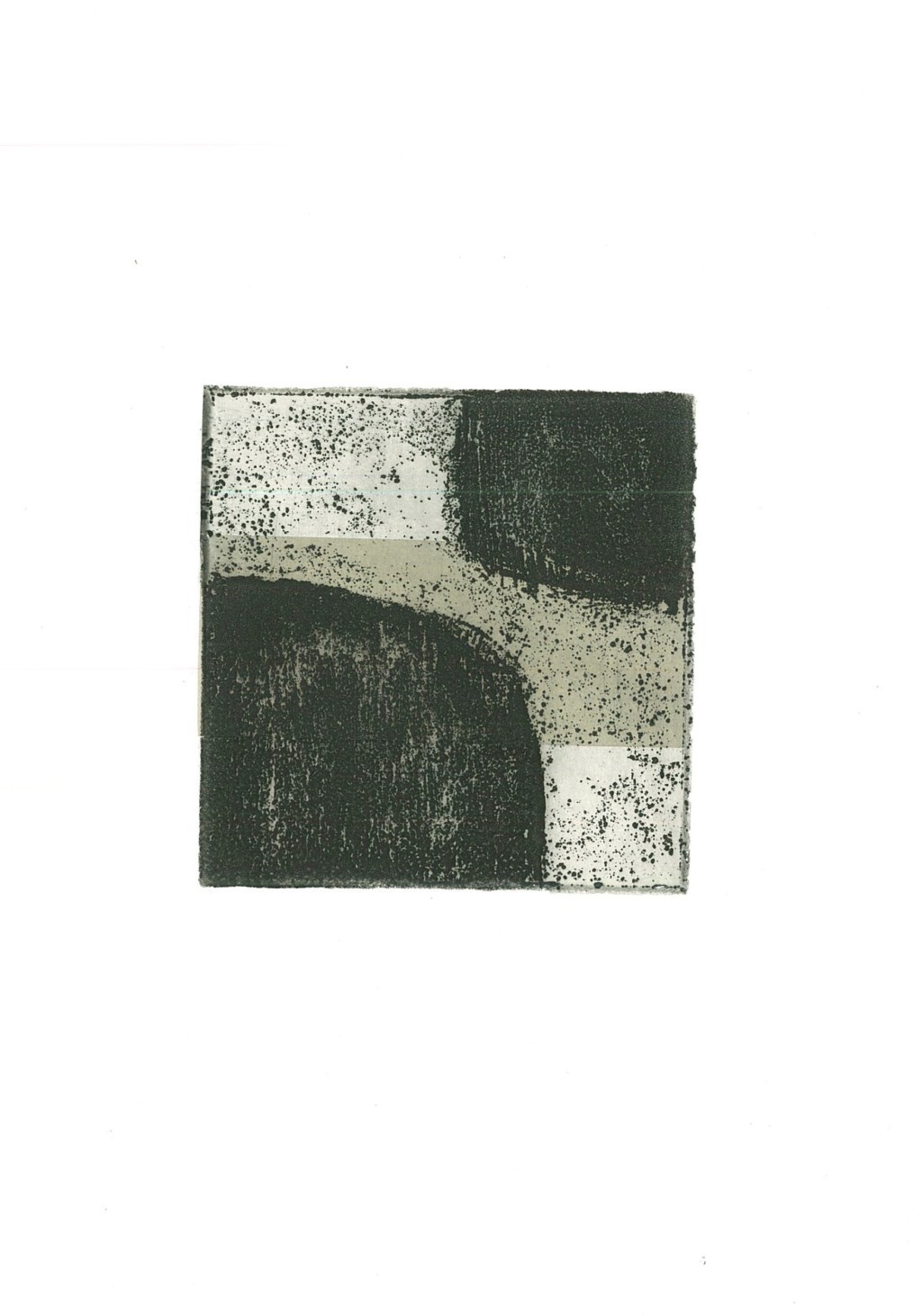

When it came to printmaking as a process in itself, I started to see how there is always this stereotype of print being a mode of reproduction and less so an art form in itself. That’s not the case, I think. You learn about techniques; you have to be logical about processes and materials. Using this artform is not as simple as making things a hundred times in a digital print. That’s why, when it came to my work, I then thought about how the context of my work fits into printmaking. Especially etching – you first start off with a hard, bending material like copper or steel, you then etch it and put it in acid, and after a few hours it transforms your image. The way I see it, when you print, it is like the image is captured in time – from material, to image, then onto paper.

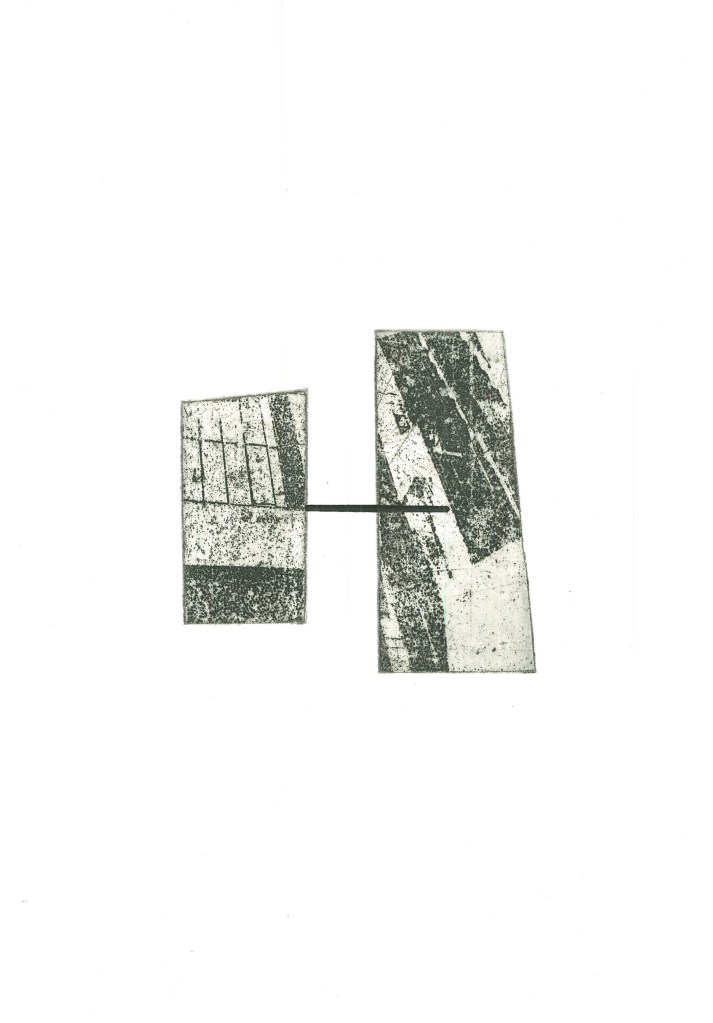

A little background – my work revolves a lot around memories, personal identities, and places. I’m always interested in the way that the landscape influences us. Within my work, you always see shape, form and texture, and that’s how I integrate these three key themes in my work. I grew up in Kuala Lumpur, in the city. I guess, naturally, I gravitated towards hard-edged forms like skyscrapers, man-made structures. I felt like, when it came to etching, it fits well with my intention of what I am trying to realise within my work. Because you are dealing with hard-edged materials like copper and steel to create your image, and it’s quite like how architects use those same materials to construct their structures. I think there’s a connection there – using the materials themselves that are already existing within the context of what you are trying to explore in your artworks. Through the transformation of the print processes, I came to make art from that material. That’s how I gravitated to printmaking.

MC: What you say about material is very interesting – this idea of allowing a material to speak for itself, to have a character.

MT: Yes, through the process itself. Once again, going back to etching, when you put the etching plate into the acid, a chemical reaction process starts to happen. This process is pretty much out of your control. Then it transforms into something totally different before you print it. I think that’s how memories are. Sometimes they can appear to be quite vivid, whereas sometimes they can be quite abstract. There’s always this tension going on between the literal and the abstract. That’s why I think printing is quite an interesting technique to explore memory.

MC: I think the interesting thing about printmaking is the amount of control that you can have as an artist – especially when dealing with material. How much control do you feel you have over the outcome?

MT: I think it’s a balance. Obviously when I do my etchings, you start off with the basic processes – cutting the metal plate into a shape that you like, filing the edges so that it doesn’t puncture the press blankets. In that aspect, you have control. But when you put it in the acid to turn it into the image you thought it was going to be… that’s where all these things start to happen which are out of your control. I appreciate it, you know? Sometimes it turns out how you imagined, but sometimes there are these happy accidents which you didn’t expect. I embrace these, because they teach you something new, about things that you’ve never expected. It’s a kind of pendulum swing – you have this control, and then learn to let it go through the process. The work takes a life of its own.

MC: To go back to the idea of you being a musical instrument maker: you have control there because you are the craftsperson. You are asserting control over the materials. But then the outcome, which is the music, will always be mediated by the instrument in the middle. The instrument, like the printmaking process, is a tool, but one which asserts its own power over the outcome.

MT: The funny thing is that when I was playing the instruments, my tutors would always say that I should learn to feel and visualise the music that I was playing. Like, what does the composer mean? That stuck with me quite a lot, when it comes to artmaking. For example, you have this sheet music in front of you, but when you visualise how it’s going to be, it becomes your own interpretation. You express it in the way you see it. My approach to making artworks has always been this way. I guess that musical aspect of me helps a lot when making my work.

MC: I’d like to go back to what you said about time, about capturing an image in time. You mentioned that all of your works are based on memories. Is this something you think about a lot?

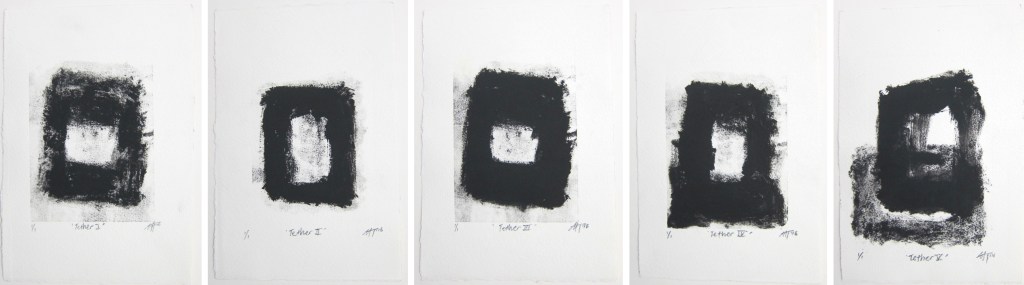

MT: When it comes to time, I always think about it as little capsules. When I’m in a place, especially within a building that has been demolished or abandoned, I always think about what happened in the past – who lived there before? All these things would bleed into my work. Also, time comes to a stop at a certain time in our lives, with each experience, and we sort of consolidate it in our memory files in our minds. When I make the prints, it sort of resembles that. Every little print has a little piece of experience, like a time capsule.

MC: I like this idea of consolidating the history of a place within a print. Your prints are very ghostly. None of them are straightforward, they’re very complex and layered. Almost like a fossil.

MT: When I’m in a place, in the mall or walking around outside, I always think about the experience itself. Being in a place, there are multiple elements that influence how we appreciate it – sounds, sight, smell, etcetera. Our bodies are the trigger points on how we react to places. I’m interested in that process of how we experience place, and my work reflects this intention to capture that process. You can see little abstract geometric shapes, textures.

MC: How situated are your works within this city, Kuala Lumpur?

MT: I grew up here, I’ve been here my whole life. It plays a huge role, because my work revolves around the places and spaces I’m in, and I’m always in KL. I get a lot of inspiration from the city. But I have a similar approach when I travel – exploring the place and realising it into the work.

MC: I read online how you went to study in the UK, and then came back to KL and were surprised by the changes to the city since you’d been away. KL feels like a very contemporary city in the sense that things are always being built and being knocked down.

MT: Interesting that you mention that, because I remember that my whole art practice had started when I had that experience of travelling to the UK from KL. I was away in the UK for a good three years, and when I came back to KL there were changes to places and structures and even the landscape. There’s this lapse between what is and what used to be, a transformation. That was interesting to me, as a starting point for me to explore further in my works. It remains a huge theme in my works, to this day.

MC: I’d like to zoom in at some specific works here in your studio. You have this very specific style of only using black and white all the time, and quite a rough texture. How did this particular motif come about? Did you experiment with other looks?

MT: I always visualise memories in monochrome, in black and white. I questioned myself about this too. I think because of my music background, I see myself as more of a composer than a musician. And when composers composed music, back in the day, they would use ink and a feather brush -black ink on the white manuscript. I see myself doing a resemblance of that, composing in a different way.

MC: I always think that musical script is an interesting thing, because its visual code – drawings, basically – but it’s also a language that everyone can translate. But, as you say, this language can be interpreted any way you want. You have to decode it, but it’s not didactic.

MT: I talked before about identity. When I make my work, I ask myself where these ideas came from within me. I grew up in a musical family, and this is why I think I see myself as more of a composer than a musician. Because, where a musician would express a piece of work written by the composer, it is the composer that has the idea, the melody, which he will visualise. I relate to that a lot. I think I visualise, I make the artworks which are then interpreted by other people.

MC: Also, the way you are funnelling this entire sensory experience of being in a city into a small monochrome print – it’s kind of like how a few notes written on a page translates into a whole orchestra of sound. It’s a distilling process, I suppose. I’m interested in what you said about identity. Are you trying to discover something about yourself when you talk about identity in your work?

MT: I think initially, the theme of identity in my work started from myself. And then it became a question of how we experience places and how these experiences form memories within us. Within that, I’m also curious about how others feel and react to place, as well. Because everyone’s different, with different backgrounds, and put in the same place, everyone will have a different experience. I like to have conversations with others. I’m interested in that process of how we react to spaces and places, how that interaction takes place within us. That’s the identity part.

MC: That makes sense, and it’s an interesting take on identity – suggesting that identity is actually based on the different and unique ways we experience the outside world. Identity as a positioning process, rather than expressing something that’s inside us already.

MT: I find it hard to explain sometimes, because for me, I’m just reflecting on how we live. It’s as simple as that. You can see elements of the transformation of the landscape, the experience of being human, how we are and how we interact in the social space we live in. These processes can’t always be seen by the naked eye, but I’m interested in them, and I try to visualise them in my own way.

MC: I would like to go back to the studio process, the actual making. You have a range of processes happening in this studio.

MT: Aside from printing, I do paint and draw as well. What I have presented here for you today is a mixture of everything. You see some digital prints, some etchings, some oil paintings, some drawings, and even a bit of sculpture.

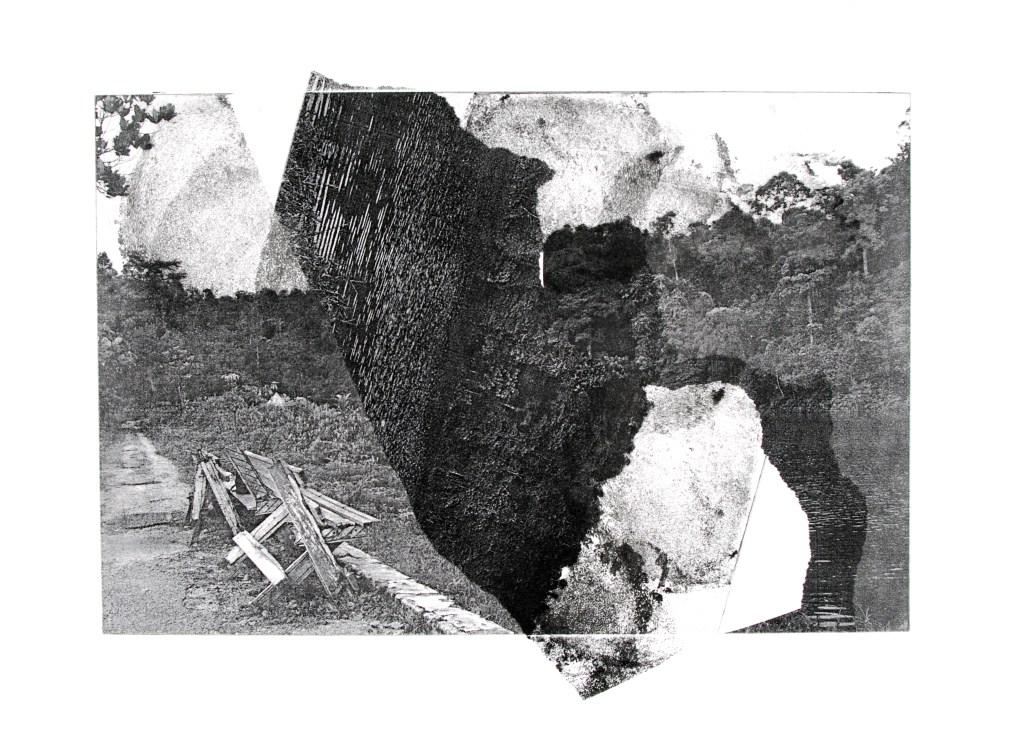

MC: It’s fascinating to see the different ways in which the same themes come about. The digital prints are the most literal, I suppose, with actual images of buildings coming through, but like in a lot of your works, you are balancing areas of intense presence with big areas of absence. Like here, there seems to be a big negative space, something torn out of the middle of the city. It makes me think about your memory of returning to KL and seeing all the old buildings demolished.

MT: Those little gaps in memories. Sometimes you can remember things very accurately, but other times you don’t.

MC: It’s like how, when you think back to childhood, you can feel the edges of an experience, the little things, but the main content of the experience is completely gone. The important stuff disappears. Like here, in this work, you have this very organic texture going on, and then this flat, blank negative right in the middle.

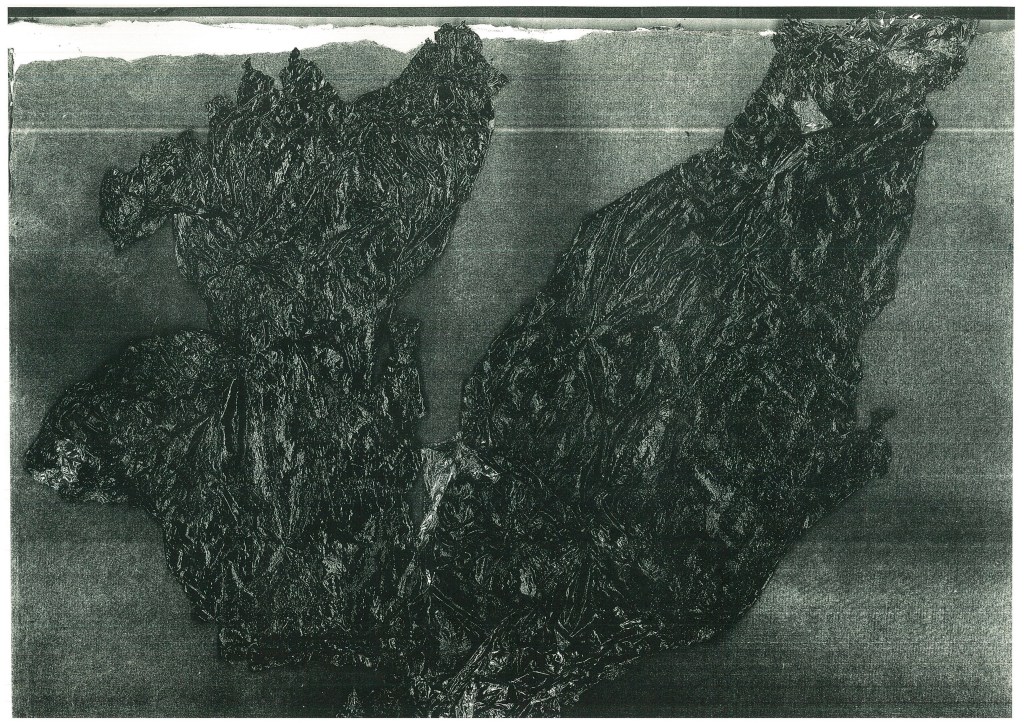

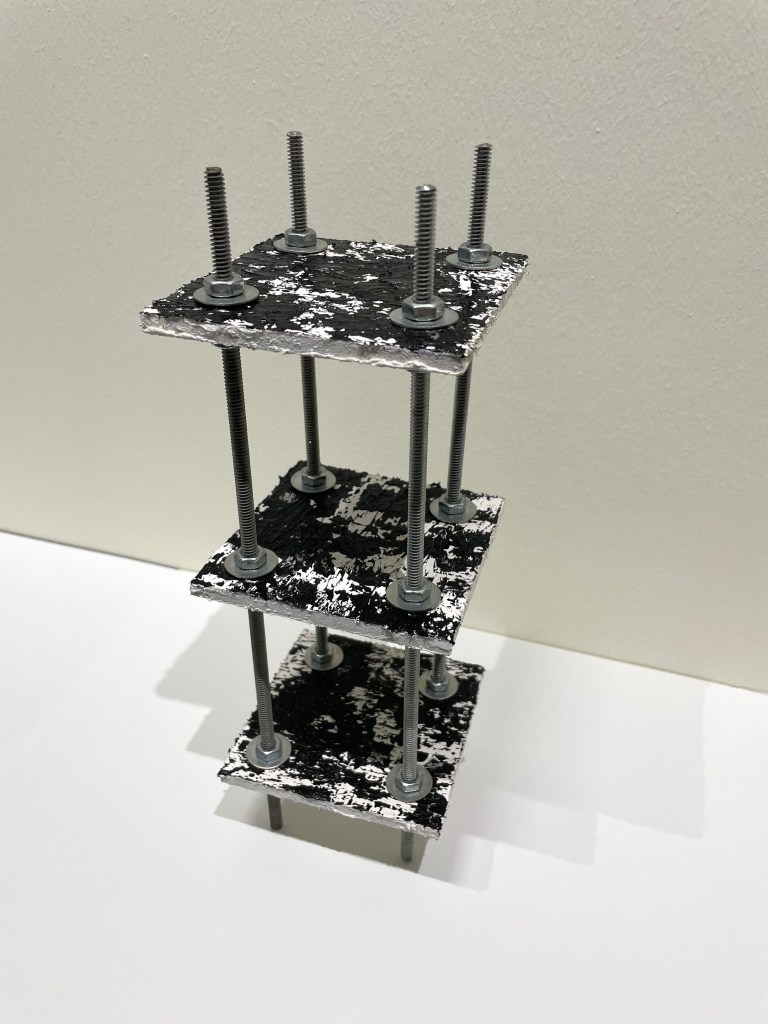

MT: Especially for these works, I took inspiration from my residency in London last year. I was in London for three months. In this residency I started to push myself a little bit. I got inspired by the sculptural elements of the materials. My residency mate was a sculptor, and we would have conversations about materials and ideas. I asked him for tips on what kind of products I would need to transform, for example, a soft material into a hard one. The key word I am interested in is transformation. These are the things I came out with.

This is basically a soft cardboard base, and I layered it with putty-filler. Once again, it’s a construction material, used in man-made structures. Then I did a mono-print on it, with acrylic paint. The idea came about when I was packing my artwork at the end of the residency. I thought I would like to, in some way, highlight this experience. This idea of movement and transferring works felt like an interesting subject to explore. So the cardboard was originally cut up to sandwich my works with for travel. It felt like a good material to start with. And then when I got back I started to use the putty-filler, not only because it’s a construction material, but also reflecting on the tips my sculptor friend gave me – putty-filler is soft but it turns everything hard. The more I used the material, the more it made sense. What I’m trying to do is fill up the gaps or pores within the material. It’s how we are – we like to fill up the little gaps in our memories.

So as you can see, there’s always this cycle of how I work with materials, from idea to concept to processes, then choosing the material, and then it becomes the artwork. When it comes to choosing the material, I always think about how it relates to the context, and how relatable it is. Like how putty-filler relates to interior space, and also to the way we like to fill in the gaps in our memories.

MC: I’m interested in this idea of transformation. It is the thread which runs through both the process and themes of all your work. You always think of building materials especially as being very fixed – like, this is steel, these are its characteristics, and this is why it’s fit for the job. But actually, these materials change and degrade over time, and that is something that is totally out of human control. That transformation is a stronger process than we can manage. And the way you humanise these very inanimate objects and materials around us, giving them lives of their own, reminds us of the ways that humans are also not fixed, and change over time.

MT: This is what I want to capture within my work. These objects can be as simple as a concrete slab, or an organic plant growing between the cracks. When it comes to drawing and painting, it creates another avenue for me to realise the more expressive side of my work. You know how in printmaking, especially etching, you have these steps to go about it. You follow a certain structure to realise the work. But when it comes to capturing experiences, drawing gives me a good instant interpretation. When I’m in a place I can take out my sketchbook and do a little drawing, capturing the moment directly.

I also feel like drawing brings out the expressive side of me, bringing me back to my musical background. When playing an instrument, I was taught to imagine the music. That interpretation helped me a lot with my drawings, in visualising ideas as forms.

MC: It’s this constant balance between process and expression. I would like to ask you what is in the future for you. Is there a particular project that you’d really like to make happen? What are you working on?

MT: I will be working with a curator in a gallery in KL next year. We’re still in the talks, but that’s the plan. Down the line, I’m hoping for a solo show as well. I also have a collaboration project in the works where I’ll be working with a musician and an artist this year. You can probably expect more of the sculptural stuff, and prints of course.

MC: Exciting! My final question is to ask for three names of other artists, your peers, who have an accordance with your work, who inspire you.

MT: My studio mate, Lee Mok Yee. And another good friend of mine in London, Laura Porter. She’s also a sculptor. One more would be my tutor, Ian Chamberlain. He’s a fantastic printmaker in the UK. We have a lot of conversations about material and process. We all have a process-based practice, where we let the process take the lead rather than us interpreting something in the literal sense.

Leave a comment