MC: I’d like to start by asking you about your journey into art. Where did you start, and when did you start to call yourself an artist?

HFC: I started calling myself an artist when I was filling out my visa entry! Actually, I never really planned to be an artist. I studied in London, and initially I planned to study photography. I wanted to be a National Geographic or Lonely Planet photographer – I was really into street photography. I already had a degree in multi-media and was in an advertising firm, but I prefer to tell my own story. That’s what prompted me to want to get another degree in photography. But the LCC course had lots of theoretical discourses, and you needed to understand, for example, Walter Benjamin’s texts. How media works and the politics behind the making of an image. I got a lot more interested in that part, over making a beautiful photograph. I didn’t like what I’d liked before, but I also didn’t really understand what contemporary art was.

Set of 8 digital C‐type prints, 16.5 x 22 inches each, 2008

In my first or second year, my friend invited me to join a show. So I brought my work, which was just me documenting my complexion changing over the duration of drinking a pint – you know, because I get Asian flush. You can see my body changing from yellow to red. When I was there to hang the work, it was just my friend’s garage. I put my prints on the wall, and thought OK, this is an exhibition. So maybe, to go back to your question of when I started calling myself an artist, there was this mini epiphany about what this whole thing was about. You think about something, you put it on the wall, people come and look at it, and you talk about it. I like that. I started to learn more about what contemporary art is – because it can be anything. But you need to work within a structure, you need to know who you want to talk to, identify what kind of platform you have. The fact that contemporary art can be anything is very intriguing to me. Of course, the tricky part is how you can survive this all. After you do more and more exhibitions, it’s just natural that you become an artist. It’s a job to me – it’s not a special unique gift. I don’t think there is such a thing. However talented you are, you still need to learn the language of how things work.

MC: It’s interesting that you mention this idea of working within the boundaries of a medium, or the conventions of contemporary practice. Because the best way I could describe your work is varied. You’re using every medium – photography, painting, curating, video essays, music videos.

Interventions on 13 found paintings (framed), dimensions variable, 2022

HFC: I like to see it as more subject-driven than medium-driven, because medium, for me, is just the tool to support what you want to say. I’m not a modern artist, and I’m not strictly speaking a studio-based artist, where you try to resolve what you have in your head on the canvas, through your medium of choice. Whereby in my work, conceptually, I have a very clear parameter. Of course, you give a little room for things that are open-ended or ambiguous, but overall I have a very clear subject that I want to talk about. I think that’s maybe the main difference between me and some of the artists that I know in Malaysia.

MC: My experience of speaking to artists in KL has been that process, and the academic practice of getting very good at one medium, is very important.

HFC: Commercially, that’s more viable. People will buy a work from a painter who has been painting for fifty years! Me, I’m doing everything, so sometimes it’s a bit difficult to sell – but that’s the price I pay. I get to make fun stuff.

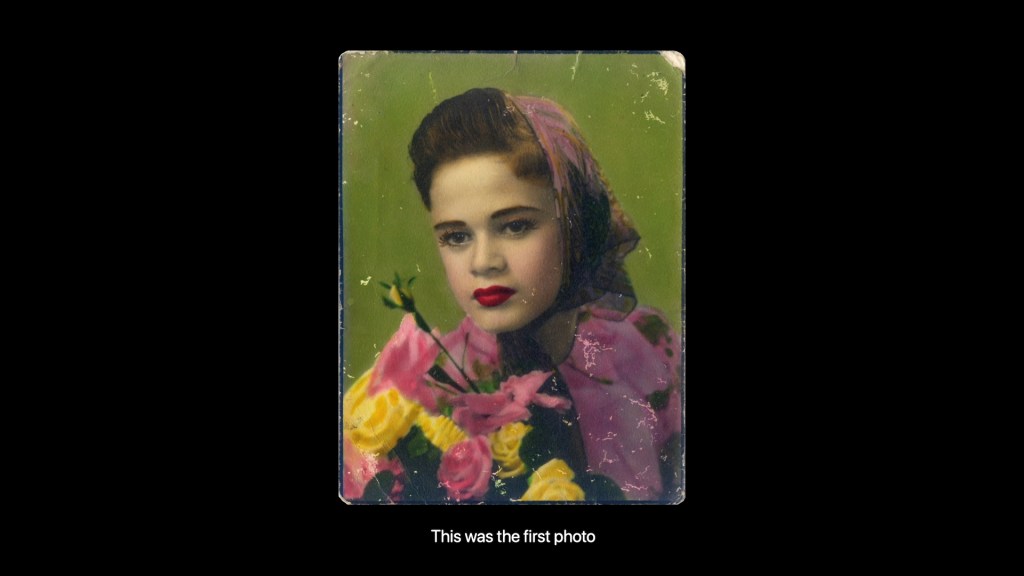

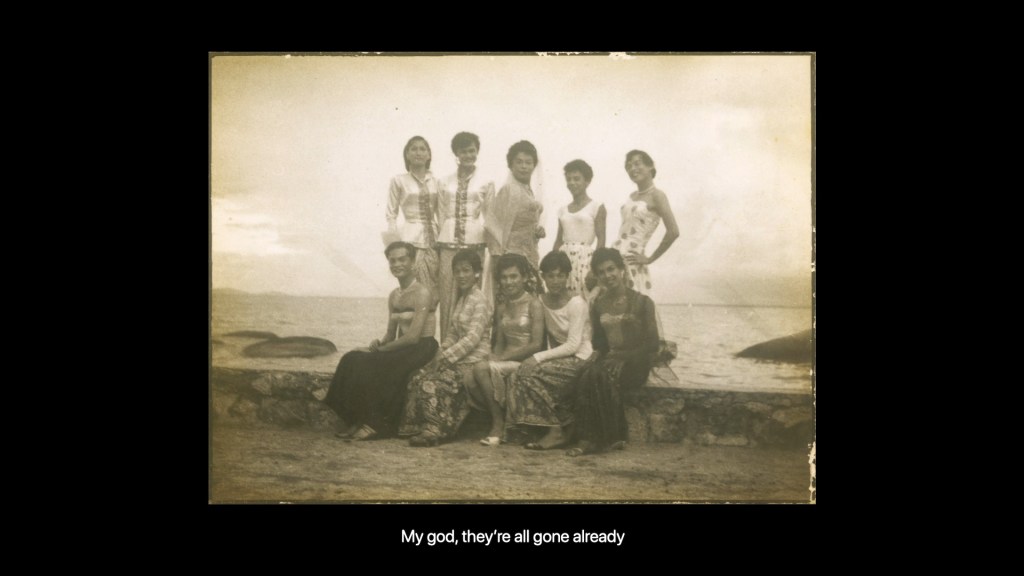

MC: Talking of medium, I’m interested in the reasons that you choose the different mediums through which you present your ideas. Maybe let’s talk about the work ‘I enjoy being a girl’. To describe it, it’s made from archival photos of a trans woman which you found here in Penang, right? What was the conception of that work?

HFC: It was an accident. I didn’t plan – I think it would be weird for anyone to go out like, today I’m going to hunt for photos of transgender people! You don’t look for these things. But I have the habit of going to vintage antique shops to look at old photographs, maybe as a way to learn about George Town. I’m not originally from George Town. I’m curious as to how people lived here before, what do they celebrate. Photography in that sense is very performative. People animate in front of the camera.

Single channel 1920 x 1080 Mpeg-4 video, 37:15 min, 2022

I was there and I saw this collection of photos of a very young boy, and then a beautiful woman. And then I put them together and it dawned on me that they’re the same person. My heart was racing. I felt like I needed to get them, immediately. I suppose I didn’t want anyone else to buy them just because they’re of pretty girls. So I bought all of them. Thank God – the owner didn’t see the connection, he just saw a bunch of photos. It was very affordable, I got a whole shoe-box of them. I went back home, started looking at them, trying to understand what was going on. But at the same time, it felt highly voyeuristic. It’s so personal, in that the person could still be alive. I felt like I had no right to do anything with these photos, until I was prompted by a curator. She was curating a lgbt show, and I thought maybe this was the time. That was in 2018.

So I started looking at the work again in 2018. I took the photos out and started bringing them around to people in Penang to ask them – do you know them? And one friend happened to know everyone in the photos. He connected me with Anita, who is not the main subject but the best friend of Ava. I started interviewing her, a bit like what you’re doing, because I needed to know the context and what was happening in every photo. She was in her eighties, so there was this race against time to jot everything down. But slowly we became friends, and slowly she kept bringing me more and more photographs. It became a project.

The video essay work that I made was just because I need to have a format whereby I could organise all my thoughts and contexts, and also to work through my relationship with Anita. Where was my voice? Otherwise, I was being more of an archivist. Also, because of the way I interview, there was no way for me to edit out my own voice because I tend to talk over people! So I included my own voice in it, it became like a conversation. Something I notice during the pandemic lockdown – because I was listening to lots of radio programmes – listening to people talking, there’s something very intimate about that. I live in a very visual world, but when I make work my ears are free. So was listening to all these programmes, which was fascinating. Recently, I’ve been listening to ‘Empire’, which is about British colonialism. It’s by these two historians from Britain, William Dalrymple and Anita Anand. It’s really amazing.

Single channel 1920 x 1080 Mpeg-4 video, 37:15 min, 2022

MC: It’s so moving, this idea. So personal, so intimate.

HFC: Sometimes, I don’t think you can plan. You don’t just write down a few key words and think, today I’m going to make work about this. It’s kind of built into your habits, your routine, your life. Something happens and you respond.

MC: I’m really interested in this idea of the archive as an imperfect medium. Particularly, I’m interested in artists who use the archive as a material in their practice. An archive is always an expression of power. Choosing what to present as truth, you’re always going to leave things out.

HFC: It wasn’t conscious, for me to build an archive. Archives come with this notion of power which I’m not sure I want. But I felt it was a responsibility. I’m the custodian of these photographs now. It’s now on the internet – for me, any archive which is not accessible loses its function as an archive. Archives must be open.

MC: – and transparent. I think a key part of that work is your own voice, the visibility of your own hand in the creation of that work. You can tell which photos you have chosen to include in the video piece.

HFC: When I was making that work, I was also thinking – what position do I have? Am I an artist? A documentary filmmaker? Because when it comes to documentary films, the language is a lot more diverse now, but in the past it tended to have this sort of moral authority, this urgency to need to tell the world about something. But in my work, I try to find a balance where it a bit more personal, I hope.

MC: One word that often used when describing your work is ‘queering’.

HFC: I wasn’t aware of it until people started using that word. Artists in general are always queering things up.

MC: There’re two camps, right? I think queering is not the same as refusal – where you reject the status quo and imagine an entirely new language, a new world. Speculative, kind of. Whereas queering, I think, is using the materials and language that already exists around you and changing it, putting a spanner in the works. That’s what I feel you are doing in all of your works – taking the material of the everyday and looking at it upside down.

HFC: Once, a writer wrote about my work and she said that it used camp, kitsch or humour as a way to disarm people from subjects that seem familiar, but then, as you say, it lays that spanner. It fucks things up a bit. It looks nice and familiar, but at the same time you’re like, what the fuck is this?

MC: And of course, queering covers all aspects of living, not just lgbt and gender issues.

HFC: Yeah, it’s more of a strategy. I used to use it subconsciously but now I’m a bit more conscious of it.

3D animation, projection, fish tank, plastic plants, bubble pumps, sound, 2:58 min, 2022

MC: I would say that one of the things that you’re queering in your work is the idea of class and status. There’s a lot to choose from. Maybe we could talk about the installation ‘Let Them Eat Salmon’. What was your original conception of that work?

HFC: Class has always been my concern. I also always had this peculiar affinity with fish. My grandfather was a fisherman, and I grew up being really spoilt, consuming a lot of seafood. I got this residency in Finland, and I didn’t really know what I was going to do. I really didn’t want to make another fish project. But in Helsinki, I noticed that a lot of the architecture was painted salmon-pink, like a Mediterranean thing. I traced that back, and found that aesthetic started in Venice. Also, salmon-pink, being a pastel bright colour, makes the city a lot brighter during winter. That’s the intention.

Single-channel video, Full HD, 15:36 min, 2022

Anyway, someone told me about this colouring that is added in to fish feed pellets, so that you can actually control the pinkness of farmed salmon. But that idea had already been responded to by a British artist duo, Cooking Sections. They did this landmark exhibition in Tate Britain about salmon, but through a very Eurocentric, environmental, ethics angle. So I thought, ok, I don’t have anything much more interesting to say about salmon. Fuck! I’ve spent all this time doing research and I don’t really have a project.

But then I thought, actually, no. They were speaking as Europeans. I’m from Southeast Asia. For example, salmon is affordable to people in Europe, it’s a common fish. Cooking Sections managed to get the Tate Modern to take salmon off their menu, stuff like that. And my first reaction was, why would anyone be selling salmon in a café? It’s a really expensive food. Then I started to think more about class difference.

What’s happening is Southeast Asia, from my observation, is that most of the middle class aspire to be the global middle class. We are trying to calibrate our lifestyle, all becoming more and more similar. At every hotel high tea, you get salmon sandwiches and scones and all that. We’re not an exclusive culture anymore. So I started to talk about salmon from that perspective – salmon as a class symbol. Not as the most premium fish – salmon isn’t the most premium fish – but more as a symbol of the global middle-class lifestyle. It’s also the idea of this healthy living, omega-3 type thing. It’s a privileged position to eat healthily, because most people just want to put food on the table. Of course now, I would say that we can afford to be a bit more selective, globally, compared to maybe ten years ago.

Takeaway foldout map, 500 copies, 29.7 cm x 42 cm (open), 7 x 14,8 cm (closed), 2022

One of the reasons I made the installation and animation was a friend I met in Finland. She’s from Malaysia. She told me that she thought the salmon fillet was the fish. That’s how detached we are from salmon as an animal. And I thought, what’s wrong with her? Has she been locked up in a cellar? But it sort of epitomises the whole relationship we have with salmon, as Malaysians. We don’t see salmon in the fish tanks. Salmon is very foreign to us. So I thought, what if I make a fish that’s alive, but in fillet form? And it prompted me to make that work. I had the voice of Sir David Attenborough as the background, as the salmon fillets were swimming around in the fish tank.

3D animation, projection, fish tank, plastic plants, bubble pumps, sound, 2:58 min, 2022

MC: That’s fascinating. I had no idea that that project was a response to Cooking Sections.

HFC: It was. Also, in general, I wanted to talk about the class divides among contemporary art practitioners. There are issues that are being championed because most of the power and resources are in Western European countries and North America. Everything is about their concerns. So you need to talk about, like, the Cold War – you need to talk about these really charged subjects. But we are in Southeast Asia. So you see artists start to pander, start to mould their practice around these Western discourses, and sometimes I do that, but I feel that if I can find a way to make it productive and relevant to our own context, then why not?

MC: I’ve noticed that so many artists here in Southeast Asia are so sick of making art about colonial times, and being labelled post-colonial artists. Even from the Southeast Asian perspective, there seems to be no getting away from the British!

HFC: The thing is, who are you making your work for? Like, there are artists who make work only for institutional curators, and others who do want to have a conversation with the audience. When I was studying in London, some of my work was about post-colonialism. But when I got back home, I realised that, actually, most people don’t care about this. It’s not that we have moved on, but it’s just been brushed aside, and people became suddenly, instantly modern. We never really talked about the colonial period. I guess, amongst academics and historians there is still lots of discourse and debate and discussion about it. But in the contemporary art world, you don’t usually see it in local exhibitions.

Interventions on 13 found paintings (framed), dimensions variable, 2022

MC: I suppose, because in Britain colonialism was sort of exported, it is something that we can talk about in the abstract, as a kind of intellectual exercise. But here, the actual site where colonialism happened, it’s within the fabric of the every day. That’s why artworks which use and explore the everyday have so much depth to them.

HFC: It’s funny; there was a quote from the Empire podcast I remember, talking about slavery. People ask, why are there so many Jamaicans in Britain these days? And then they invited a guest, Vincent Brown, who published a book about slavery, and he said, ‘I’m here because you were there’. We were connected already. We don’t need to discuss what kind of relationship it was – a bloody history – but it was a relationship.

I made a willow pattern series when I was studying – willow pattern, the blue and white chinaware. I read this story about willow pattern. Back in the sixteenth or seventeenth century in Britain, importing chinaware from China started to get too expensive so they made their own. They had people writing these love stories for the willow pattern designs, like couples eloping. A very Western romantic story. In Chinese culture, you don’t elope and run away, you stay and suffer! Chinese love stories are all about suffering. Willow pattern became a kind of household subject, and in London I saw it everywhere, in every flea market. I was like, why does this look so Chinese and at the same time, so British? I was interested in exploring that idea. I started making cyanotype prints of all the oriental follies I could find in London – in Kew Gardens, Holland Park, they have all the pagodas and floating boats and whatever. So I painted this fake oriental landscape on cyanotype paper, and I folded them into objects that looked like chinaware – plates, cups, teapots, chamber pots, that sort of thing. That was my take on post-colonial art.

Set of 9 digital C‐type prints, 20’’ x 24’’, edition 5 + 1 AP, 2010-2012

I bring this up because that work was well-received. I got into competitions selected by Saatchi, the Photographer’s Gallery. But, showing this work in Malaysia, people don’t really have the context. Postcolonialism, through this kind of presentation, is not really understood.

MC: I think maybe we are just used to that kind of language over in London.

HFC: Local geography is extremely important to me. I need to work with context.

MC: Speaking of local geography, I wanted to ask you about how the city of George Town, where you make your work, affects your practice? You’ve done a lot of performance based, public intervention stuff. How does the character of this city affect your work?

HFC: I’m not sure, but I just like the size of a town where I can just cycle and get everything done. I came to George Town with my late partner. It was just convenient; he had business not far from George Town. I’ve been here for twelve years now, and it is now home. There’s a very strong sense of being very communal, which I enjoy. Working with friends, collaboration, talking about ideas. I think Kuala Lumpur is a mega-city with many suburbs, hard to navigate, as you know, from one suburb to another. A bit like London, too, impossible for people South of the river and North of the river to constantly meet. Here, the scale is small and I like the size of it.

Set of 9 digital C‐type prints, 20’’ x 24’’, edition 5 + 1 AP, 2010-2012

Another thing about George Town is that everything can be made into a merchandise. I don’t mean it in a bad way. Because of that, some of the materials that I use are from people merchandising their anonymous memories, in the form of postcards and photos and all sorts of things. There’s a lot of discarded residue of things from the past everywhere. Sometimes its part of the decoration, and sometimes it’s used to create a certain charm for a café or hotel. But in general, if you give me enough money to survive, I think I could go to any city and just find a way to understand it and make it interesting. That’s what we do, no? We try to form a connection. This is my way of doing it.

MC: So you’re interested in the concept of locality in the broadest sense?

HFC: Yes. And in this place, I want to continue to nurture this relationship. I think sometimes – and this may be class-conscious thinking again – people kind of cherry-pick where they want to move to. They don’t need to form a relationship with the place because they can buy comfort, they can buy the environment, they can select the specific nice suburb they want to be in. But if you have less, you can work with people to make the place better for yourself and everyone else.

MC: Leading on from there, I was wondering if you could speak a little bit about the concept of PechaKucha, which I know that you introduced at the gallery that you ran, Run Amok. It’s where you invite different people to speak about their practice for twenty minutes at a time.

HFC: I just wanted to create a format where it doesn’t take too much time for the organiser to make things happen. I think everyone has a practice, whether that’s being a facilitator, a community worker, a historian. That’s practice, in general. So you invite one person to give a presentation, and then after that presentation, that person will select the next speaker. So, it decentralises the decision-making process, so it’s not always me selecting people. It’s a good way to decentralise power and see how another person sees the world. But, the project didn’t work because, in general, people don’t like to talk about their practice. It can be very daunting to some people.

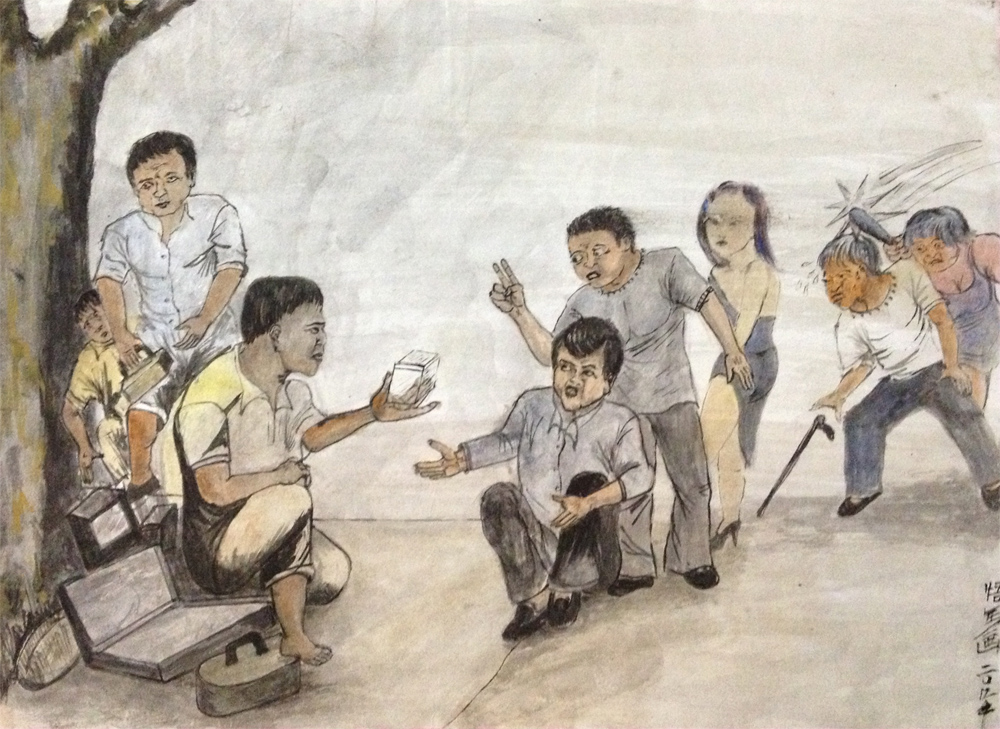

MC: I was thinking about this in relation to your artworks in which you are kind of facilitating things rather than directly creating. For example, the work where you found that artist making drawings on the side of the road, and you displayed all his work in an exhibition.

HFC: He was an outsider artist. It wasn’t planned. When I first moved here, it was because I wanted to run a space – Run Amok. That was our first exhibition. I was writing to all the artists I liked but they didn’t really respond, because they didn’t know about the space yet. But I saw this artist in the flea market, saw his work and really loved it. There’s something really animatic about his stuff. He painted a lot of ghosts, and claimed that he could see ghosts. And I talked to him about showing his work in my space and he said no. He said, just buy my works, I don’t care what you do with them. I just bought them, framed them, and so I had a show. But, during the installation, he came along. He was so proud to see his work on the wall.

I thought that an exhibition doesn’t just have to be by artists who only make work through the artmaking language they learned from institutions. I mean, there are interesting ideas everywhere – how do we frame that experience? Through working with him, it expanded my imagination regarding what an exhibition could be. You also free yourself up a bit by not having to deal with artists, because they’re not the easiest people to deal with! It’s not like London, where they churn out thousands and thousands of artists every year. Theres so many to choose from. In George Town, we have three colleges, and in all the art courses they have to do quite a bit of applied art. The system was designed to prepare students for the commercial world. They need to find a way to survive rather than just thinking about artsy-fartsy whatever. It’s geared towards more practical skills. That’s why things like research don’t often get paid, even though research is so important – that’s how you understand your subject.

MC: I recognise, in your work, very little ego. You’re really generous in your practice in giving space to others.

HFC: There is ego. To do what we are doing, you need a bit of ego. You need belief in what you do to have that confidence. A healthy dose of ego, for me, is confidence.

MC: Nevertheless, I like the way that you give space to others in your work. I think, ultimately, it is the best way of keeping the art world alive.

HFC: See, London is so fragmented. There’re so many different cliques. You have the artists circle who have already made it – the Lisson Gallery crowd – then there’s the Peckham branch, for example. They all have their own scenes, and I when I was in London I felt that it was not easy to belong anywhere. It’s not easy to survive London, too. If you want to have a practice, you have to downscale your lifestyle. Materially, you can use less because you’re putting all your resources into making your artwork. You’ve got to build your network, show up at the right exhibition openings, rub shoulders with the right people. It’s a very different world.

MC: Agreed! Perhaps this leads us to our final question. Please can you recommend me three names of other artists who you are inspired by, or who you have inspired?

HFC: Not in any direct order. The first person is called Zaidi Musa. He’s a one-man publisher. He’s on the East Coast of Malaysia, in Kota Bharu, and he used to have a stall in what the call a knowledge market – it’s more like a flea market. He’d be selling socialist publications, because he himself is an ideological socialist. Then he set up a little stall outside the mosque, so people would come out after Friday prayer and look at his books. He thought that that would be the best time and space to have these conversations! He also publishes books from time to time. I just find him really inspiring, because he really believes in what he’s truly passionate about, he’s walking the walk and making things happen. Even being as small as just one person, he is slowly injecting quite a bit of new energy and a new way of thinking into a city which is deemed to be a bit more religious than other parts of Malaysia. Also, he was a food delivery man because he doesn’t make much money – just doing whatever he could to survive. I find that very inspiring.

Another friend; her name is Anitha Silvia, she’s from Surabaya. She’s a walking activist – she walks everywhere. By walking I mean you physically carry your body to be present everywhere. For her, she wants to explore women’s presence in public space. How do you place safety marker pins around? Like when you see another woman vendor, for example, that becomes one of your points of safety. Being a man, I never really have to think about that. She also feels that the best way to understand any city is to walk. Every time I see her, it’s kind of hard-core because she only uses local transport and walking! It’s amazing, you’ve got to meet her. And everybody knows her, because by walking everywhere she made herself present. People feel safe around her.

She’s also doing research on the Eastern Archipelago, which is from Sabah eastwards to Papua New Guinea. She was researching the Tamu market culture, which has been practiced for centuries, where women will come out and barter their own produce. She sees the market as a place for women to get together to empower themselves.

Another name is Sharon Chin. Last year, I was struggling with my practice, thinking that I don’t know how to survive this, how to be commercial. She recently encouraged me to apply for a Prince Klaus fund and British Council ‘Moving Narrative’ project. So Sharon Chin is one of the few artists who really, truly, genuinely believes in growing together. She always gives a nudge to artists she likes, and she’s always paid attention to younger artists as well. She used to make work that carries a sort of Western institutional sensibility – installation with objects. Now she is switching to things that she feels are a bit more democratic, such as screen-printing. That way, she can have many versions of the same work, it is made affordable so friends can actually buy it. Instead of just relying on one, single, super-powerful curator, why not just make your work affordable to a big group of friends who can support you? She’s a hopeless romantic, but she’s not impractical. She has a very clear vision and she’s trying to nudge things towards her ideal world of artmaking.

So those are my three names. I feel that artists shouldn’t just get inspiration from other artists. There’re so many amazing thinkers around us – filmmakers, writers, journalists… They are friends and I am really inspired by them all.

An article about Penang outsider artist, Wu Ma, written by Hoo Fan Chon: https://oforother.malaysiadesignarchive.org/wu-ma-of-thieves-market/

Leave a comment