MC: I would like to start by asking you to tell me about your journey into art. Was there maybe one moment which made you an artist, or was it more of a gradual thing?

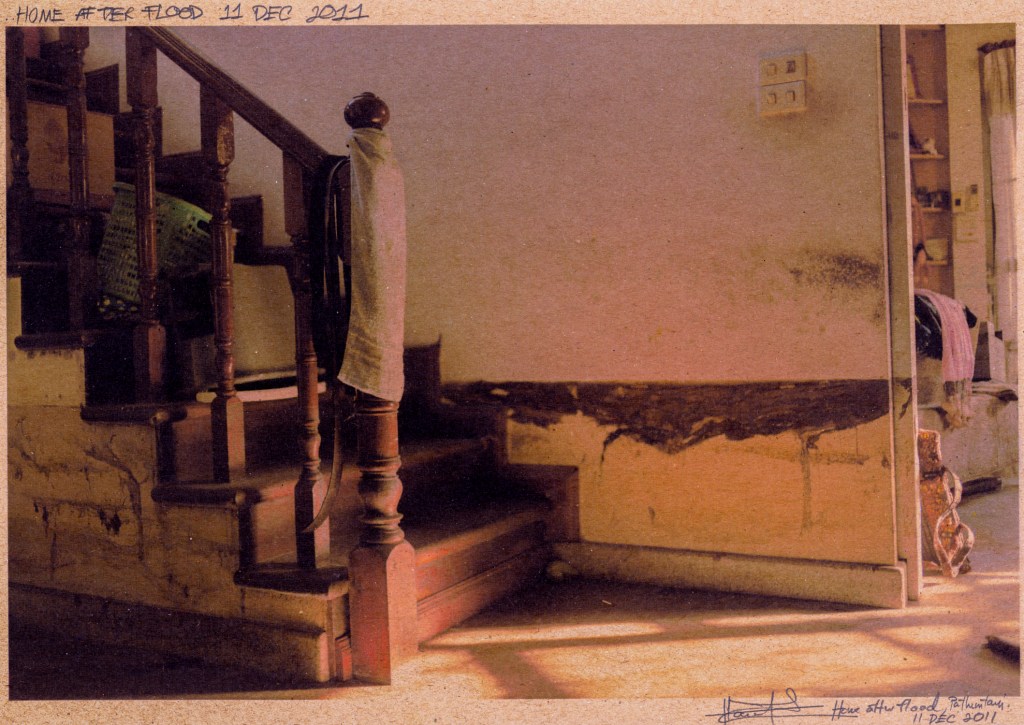

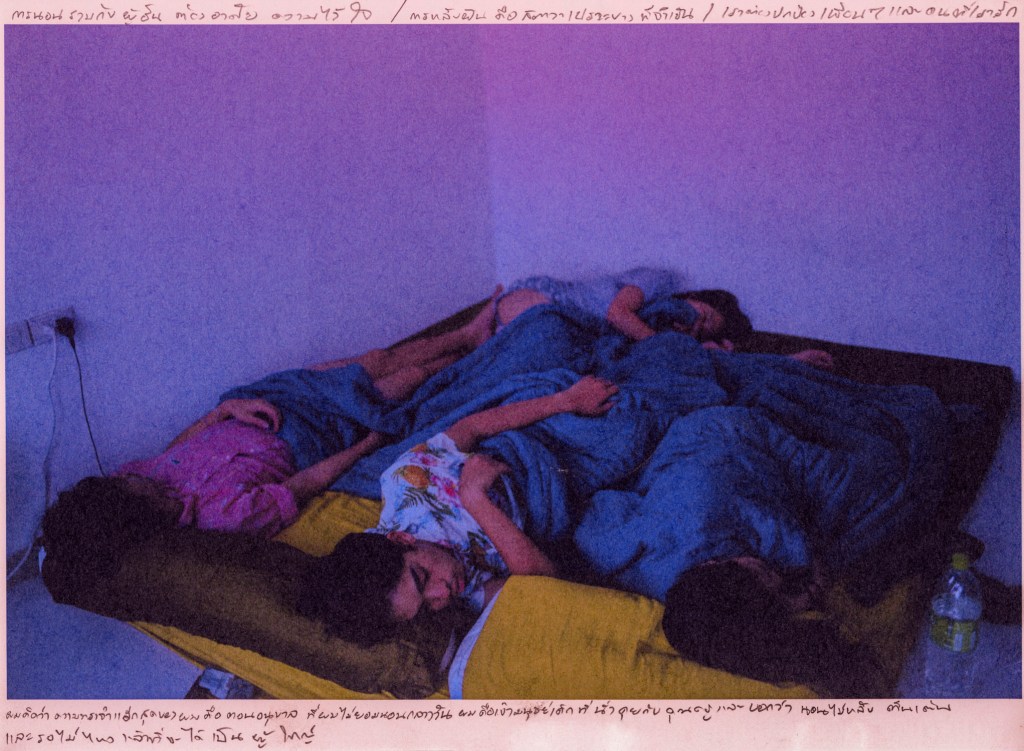

HS: I have prepared this book of my photographs for you. Actually, I always wanted to be a photographer. These are the photographs that I did when I was in high school. I grew up in a province called Pathum Thani, which is on the outskirts of Bangkok. The book actually begins with the flood in 2011. The story begins when my house flooded, and I had to move away. Here you can see my village after the flood, when everyone had to dry out the furniture. You can see the line there where the water has dried.

MC: Was your main aim to document your experience of the flood?

HS: Yes, I just documented, I took photographs. Then I left. Years passed, and then I looked at it again and gained an understanding of what was really happening. I think my practice is quite different from other photographers. For example, they will set the date that the work has been produced by the date that they took the photograph. But for me, I think the work exists only when I understand it. When I conceptualise it. For example, this work, titled ‘Cumulous’ is from 2023, but I actually shot it ten years ago.

MC: So it takes a long time for you to sit with the works to gain understanding. But when you conceptualise a shot initially, does a lot of thought go into it? Or is it quite spontaneous?

HS: I didn’t think about anything when I shot the photographs, but I think these kinds of processes are quite crucial for me. I have my own printer, and I print the picture out and see it as an object. That is a crucial way for me to understand that time. Also through notes and sketches, I try to understand the moment.

MC: What strikes me about these works is your sense of the materiality of the photograph itself; the printed photographs, the sketches on top. Is the materiality of the medium important to you?

HS: I don’t think about it when I’m doing it, but looking back on my practice, I do think it’s very important.

MC: Looking through some of your previous work, I noticed some gradual changes in your style. You’ve moved through photography, installation, and now you’re moving into film in your upcoming show at Bangkok CityCity Gallery. Can you explain that transition?

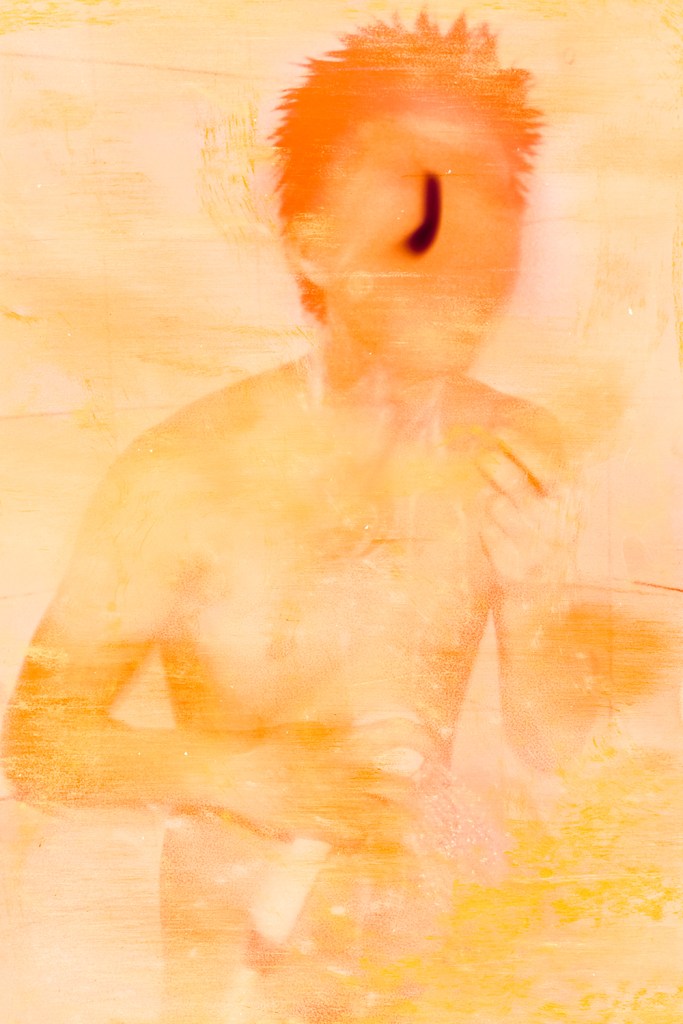

HS: Of course. This book has my first photographs, when I really wanted to do documentary photography. But then I started to realise that my way of thinking about photography is very different from, for example, journalist photographers. I’m interested in storytelling in a photograph, and so I moved from storytelling to more conceptual photography. I moved to staged photography, when you prepare something and you photograph it in the studio. It felt good, because I don’t have to deal with people. But at the same time, I felt that I should mix them together, and that’s what this exhibition is trying to do. We have the documentary style and also the staged photography.

MC: I guess what you’re really dealing with there is the idea of truth, of seeing how far a photograph can convey something authentically. In traditional documentary style, it’s almost like the photographer doesn’t exist, like this is a window onto the world. Staged is kind of the opposite. Are you interested in the idea of authenticity?

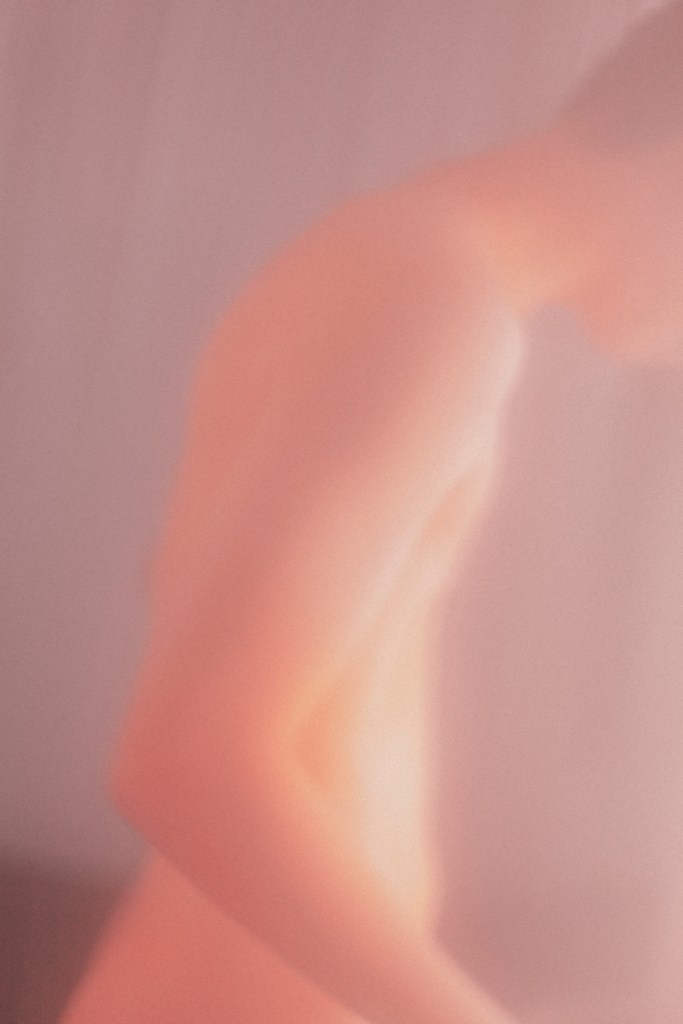

HS: I think so. Actually, to go back to when you asked about the shifting point from conceptual photography to film – this exhibition is about my experience being a subject in another person’s existence. It’s how I try to deal with it. This book happened after I went to art therapy. I think I want to question the authority of the storytelling of the subject and the object. You know, being a photographer and being the subject. This work is trying to deal with it. This work is the first time I have put pictures of myself in the work.

MC: That’s a very interesting jumping off point for an exhibition. I always think that the medium of film montage, with photography, is very interesting. It has its own interesting history – thinking particularly of Nan Goldin, who I know has a significant influence on you. It does something weird with time, because it’s a build up of these snapshot frozen moments.

HS: I do think I wanted to be a filmmaker when I was younger. It’s how I think about photography – not linear, but time-based storytelling. It happens because my perception of time is very bad. My memory was quite confusing when I was young. With this delayed understanding of things, it really makes sense to take photographs, and then to arrange them in the understandable time.

MC: A way of rebuilding yourself, using these records. It’s interesting to think of photography as a leftover record of a time, rather than an immediate production of that time. I noticed that there is a lot of work in your practice based on the body – the experience of being in a body. Could you speak a little more about that?

HS: I think it’s something to do with the relationship between a man who has power, and a man who has less power. Like the photographer and the object. That was my own experience when I was younger. Both me as a photographer and me as an object. I try to find a way that presents the body as – not exploited, but fragile. Vulnerable, but at the same time, becoming a monument. I believe that photography is a monument of time.

MC: I was thinking about a previous exhibition that you did which was about dictators and trying to regain a sense of youth. It was a very install-based show, including some sculptural works. What was the thought process behind this?

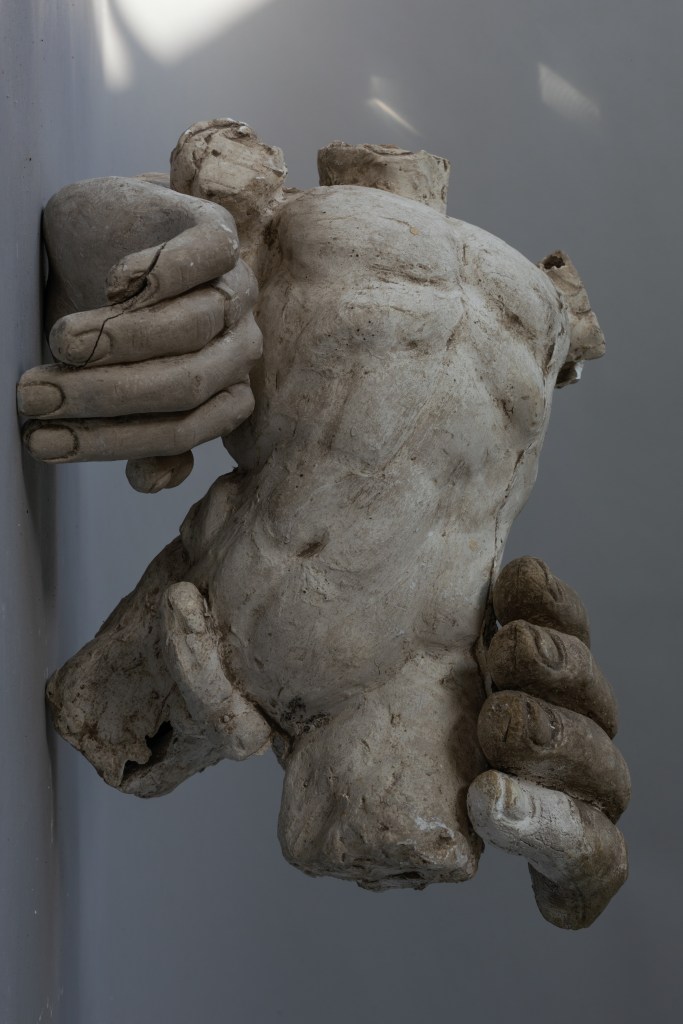

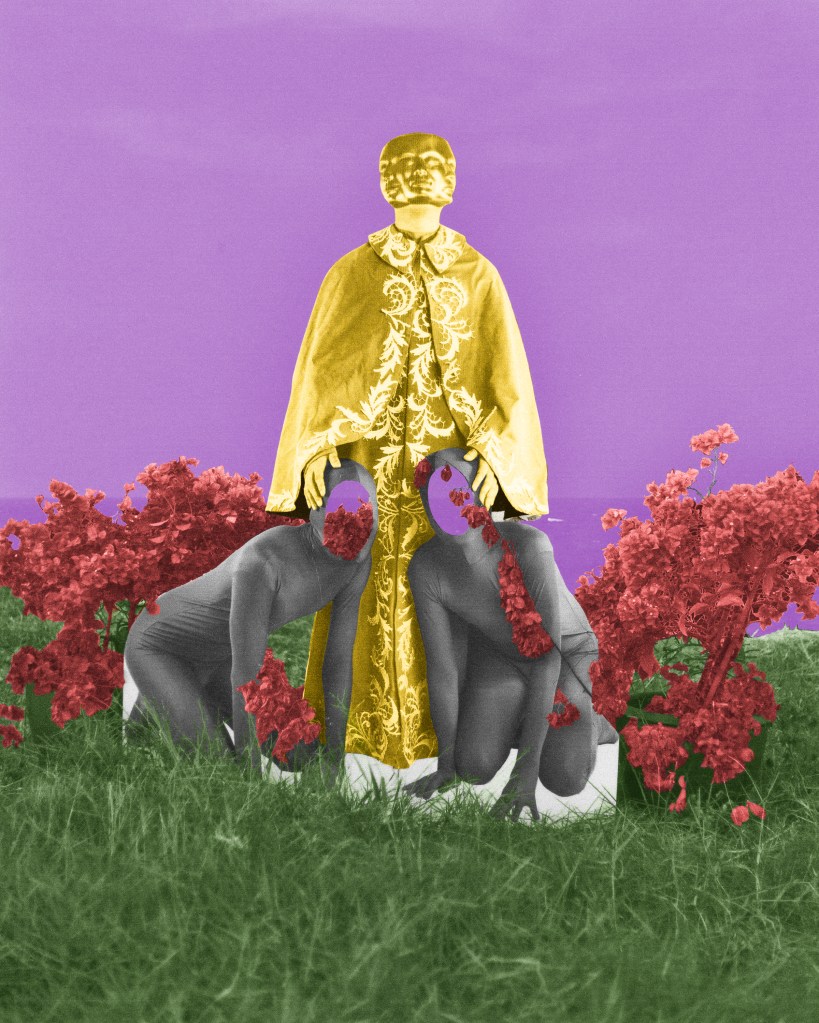

HS: That work was 2021, 2022 – a little bit after Covid. This is a shot of a broken statue – actually, a prototype of the statue – a political one, which the government kept quite in secret. I asked permission from them to take photographs, but the fact that this prototype was not allowed to be seen publicly is interesting, because it shows the weak point of this immortal being. When you talk about monuments, you mean something immortal. But the fact that this prototype is broken is the opposite of that fact. To go back to that exhibition, I was trying to create an ideal museum where people – especially Thai people – can see the decaying body of the dictator. I was thinking a lot about museums, objects, and installation.

I work a lot with the progress of the image: like, for example, if I shoot your portrait, and then over time your portrait became a statue, and then maybe a painting. This happened a lot with Stalin, with iconic people. The ultimate, supreme class in the progress of a photograph is becoming a monument. So, in that exhibition, I tried to transform my photograph into something like a statue. Immortal. We have a lot of news stories here about how, for example, a house burned down, but the portrait of the king remained un-burnable. We also hear news of people seeing an image of the king in the clouds. That is very poetic. I think the top achievement of a good photograph is when it comes into your mind like that. Like, you don’t have to see the photograph, but you see a cloud and you think of the photograph. It is the supreme icon.

MC: It transcends its material place as a document, an image on paper. It goes beyond itself.

HS: I am very much interested in that mutation of fact and truth, to becoming something else.

MC: I notice that this mutation process mirrors the changing processes of your practice – from the documentation of real life to the more staged, conceptual, install-based work.

HS: Its just another work. There’s the personal work, and then there’s the work which talks about photography itself as a political tool.

MC: Your work has always been quite political, and you have often explored marginalised stories. What has been your experience of dealing with narratives of history which are untold?

HS: I think it began in 2011, during the flood. There were lots of people protesting against the government – the Red Shirts. At that time I was very young, and didn’t understand what was happening, but I remember one day, where me and my family went to the central city to clean the street. It was very fun – that I remember. But four years later, I was in college and I started to become interested in politics. I realised that three days before the cleaning day, around one hundred Red Shirts, protesters, had been massacred in that area. It was a campaign of the government against the protesters. I felt very guilty and shocked. That was the beginning of how I see photography as a political tool used to distort people’s memory.

This work begins with me being a student during that time. As students, we had to go to a military camp – the political brainwashing of the youth, at the same time that the protest was happening. That way, the youth didn’t know what was going on.

MC: I suppose, after so many years have passed, you can look back on that time and understand how you were being manipulated. Amnesia is very important for any government to maintain its power. I wanted to ask you a little bit about your experience as an artist here in Thailand, particularly Bangkok, given the censorship that takes place here. Is this difficult to navigate?

HS: That’s a very hard question for me. The answer might not come from me alone, but I have heard a lot of people analyse Thai artists. People usually analyse it through the idea of a generation gap. For example, if you look at the Old Masters, people now aged eighty or ninety, the relationship between art and the monarchy is very legit. I’m not saying that they support the dictator, but it’s something to do with the structure of power at that time. When any of the older artists are against the dictator, the way they deal with this is quite direct and in-your-face. For example, in the late fifties, they were quite direct. But the artists under forty, they deal with the political situation in a more poetic or alternative way. For example, a good friend of mine, Nawin Nuthong, is dealing with gaming and cartoons but it is also very political. And Tanat Teeradakorn, he’s also dealing with the political but through sound, sub-cultures, invisible things.

MC: Continuing in this vein, could you give me three names of other artists who have some kind of accordance with your work, who inspire you?

HS: Nan Golding, of course. When I was young, I wanted to be a National Geographic photographer – like, where you have to go to India to take photographs, you have to be far from home. But then I saw the work of Nan Golding, and all the people in her work are her friends. It’s a great idea, I think – putting a picture of your mum in MoMA is such a great idea. If I take the photograph well enough, maybe my mum could be in MoMA! It’s this idea of turning ordinary things into something monumental.

I think I would say, Guillermo del Toro, the film director. I like him a lot.

Also, there is a painter here called Tae Parvit, who is represented by Bangkok CityCity Gallery, where I first knew his work. He lives in LA now. It’s quite personal, but my work is often dealing with my experience of being in a toxic relationship. I was feeling… not free, controlled. But when I saw Tae Parvit’s exhibition, I could feel the freedom of the painting. The exhibition was called ‘Afternoon Person’. It was a very wonderful show.

Leave a comment