MC: I would like to start by asking you to recount your journey into art. When did you first start to call yourself an artist?

B: I never did. I still go by the title of painter, even though I do more than just painting. I get bored easily. So when I get stuck into a routine too much, then I’ll hang it up and break away to explore other stuff. Academic-wise, I came from more of a science background. I was trained as an engineer, but I failed. So I switched back to a more comfortable practice, visual art. Southeast Asian families never encourage their children to do anything other than big-salary employment, and I tend to be the naughty one.

MC: Why were you so drawn to street art?

B: Street art or outdoor works are cheapest to create in large scale practice without having to bother with storage issues, also more direct instant outreach in comparison to gallery exhibits or studio works, especially when I was still a nobody. It invades public view and forces them to be visually engaged, similar to billboards.

MC: Street art has a very specific relationship to the idea of the personal, right? It’s anonymous, and it’s the opposite of private – in the public realm.

B: Yes and no. Before the era of social media, street art can be anonymous because behind-the-scenes process are barely exposed to the public. Twenty years fast forward with improvements of smartphone video technology pairing with social media content video clips behaviour, the dynamic has switched from personal expression to mostly advertisement purpose, street art making has become almost like a branding campaign in a public domain in both physical real world and digital realm. Anonymity is now a matter of choice.

MC: So you are trying to elucidate a certain response with each work? I feel that your work is very political. You are trying to say specific, relevant things.

B: We humans are social creatures, you just can’t escape politics in a society, everyone have their own unique needs and interests, everybody has their own opinion. Politics is just part of our life in society, whichever scale it may be, globally, nation-wide, neighbourhood or even among housemates. Politics fascinates me in terms of power, influence and hypocrisy of human nature, mainly from a psychological point of view.

MC: Are you unhappy with the idea that the meaning of the work is taken out of your hands?

B: I suppose no, stoicism comes in handy. I tend to contextualise my work in layers so that everyone gets to at least have something to take away without having me to overly mansplain every reasoning, it gives space for wondering without being directed, and convenient for me to slide in some hidden messages when I feel like being cheeky. Since I’m in fine art not public service announcements, therefore I get to flex on the luxury of setting my own rules of communication.

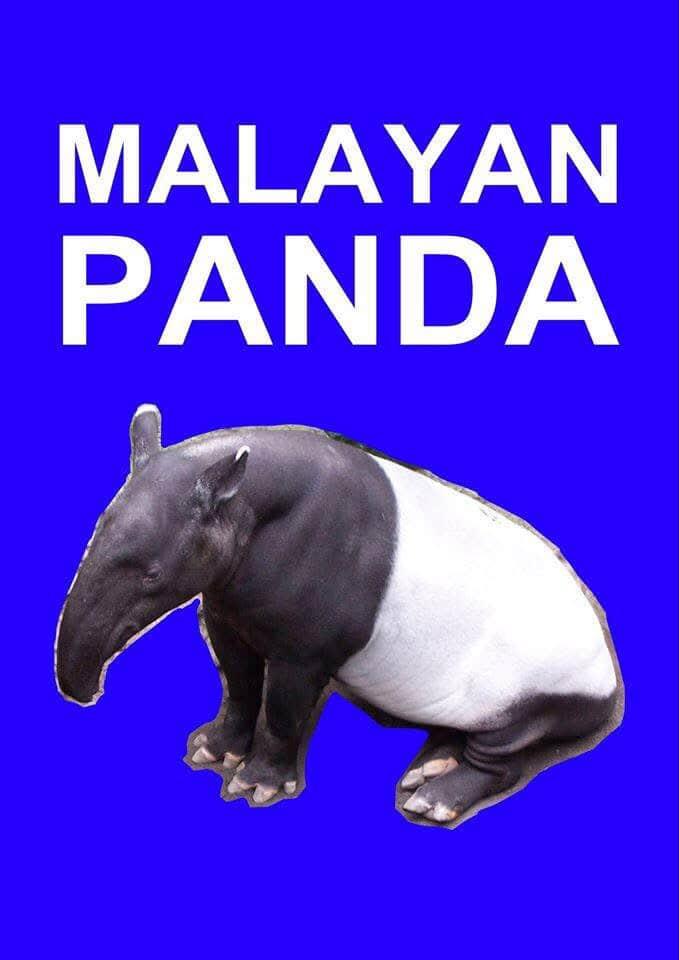

MC: I was researching your practice, and saw a lot of stuff talking about Malaysia, the state, the government. Your use of the tapir as a symbol, in contrast to the Chinese panda, in particular. Could you tell me a little more about that?

B: See a Panda, and you’ll think of China. See a Kangaroo, you’ll think of Australia. I started off by asking if there is any animal that is visually endemic enough to represent the Malaysians, like how Panda is to China. Even though Malayn Tiger is the national animal of Malaysia, tigers cover the whole range of Asian nations, and it’s not easy to tell the species apart. Hence Malayan Tapir is the best choice. This topic on Malayan Tapir is an ongoing process that I would frequently surface in my practice, it’s an introspective on myself as a Malaysian, and to understand what it actually means to be a Malaysian. The idea of a nation is big, but I can relate only to a city, beyond that is difficult for me to comprehend, and I prefer not to rely just on other’s perceptions. I want to be honest to myself.

MC: Are you interested in tapping into the history of Penang in your work?

B: I’m still figuring out a suitable approach. I don’t fancy the history of Penang from just the legacy of British occupation, which is overrated by the mainstream media. I’m curious about life before the white colonists’ influence arrived.

MC: Is it important to you that there is a very distinct Malaysian identity?

B: Of course it is important, it involves national dignity. Our identity has always been multicultural, and it can be misleading when one tries to oversimplify it. Hence it’s difficult to have just a single imagery representation. It has been my on-going subject matter in terms of exploring and deeper understanding.

MC: Is this why, in your work, you never represent things directly? You always use symbols.

B: Correct. I have to go around beating the bushes. I think that it is part of our culture to not criticise directly.

MC: Could we talk a bit more about the materiality of your work? You mentioned before that you wanted to be known as a painter rather than an artist, but you don’t only paint.

B: In a way that’s a hypocritical statement, but I am sick of the word ‘artist’ because in Malaysia, the word applies to TV celebrities. Simplifying to just a painter saves me from having to explain what I do all the time. Unless the chat is further into deeper conversation, otherwise I’m fine to be known just as that. I have a few other artist friends who self-proclaimed as taxi driver and astronaut.

MC: It’s hard to get a clear sense of your whole practice by just looking you up online. But at the moment, it seems that you are making a lot of small sculptures, sculptures in the city, social interventions, paintings on the wall. Also a bit of film?

B: I don’t want to be tied down to just single medium identification, it encourages a sort of expectation on me and takes away my freedom of choice. Diversifying my practice helps with my thinking process, it helps me to see broader probabilities and improves my innovative ability. I don’t identify my video works as film because I don’t quite speaks their language yet, and my clips are more relatable to TikTok sort of clips. I used to fancy doing 2D animations quite some decades ago, but the tech was not as convenient as nowadays. Hopefully when I hit a jam in exploring wooden sculptures, maybe I can revise some animation projects.

MC: You’ve also moved your work from the street into the gallery. How was that transition for you?

B: I don’t produce street works as often as I used to anymore, my age is catching up and it holds more value to create studio works in comparison to outdoor works in which the latter will deteriorate way faster due to the nature of tropical climates and other environmental factors. Occasionally I will accept outdoor commission if the pay is suitable or at least if the social value is sufficient. The transition is pretty easy due to the past decade of frequent involvement in organising group shows with Hin Bus Depot.

MC: Your work is characterised by humour and naughtiness – almost a childishness. Why is it important that your art is funny?

B: It’s an attitude that I am projecting, also sometimes it’s a mood setting. Sensitive contents that could easily trigger anger are toned down with sarcasm, it helps to delay hostile response and slot in a bit of thinking process, rather than escalation. Stupid contents that triggered my anger (especially absurd political statements from authority) will be ridiculed in naive approach, it’s my visual language to cope with the world. Postmodernism allows this kind of freedom.

MC: It’s nice that you are able to bring some fun back into the gallery. I don’t think I’ve ever been to a funny white cube exhibition.

B: Also, it’s kind of a helpless action. You disagree with this political outcome but you’re powerless to do anything about it. You either fall into depression or choose to be angry, and you get yourself into trouble. So, what can you do? The least you can do about it is laugh about it. That’s how you can empower yourself to move forward and get on with your life. So actually, the humour is quite sad and helpless.

MC: I would describe your work as a kind of resistance to being ignored. It’s a statement of an attitude that won’t be ignored.

B: I’m at the losing end anyway, so I’m just gonna salvage whatever is left!

MC: Can you describe what you’re currently working on?

B: I’ll be having my solo show in December, in Hin Bus Depot. The show is mainly on the topic of tourism, overlapping on creative economy, and a personal protest against the minister that is currently holding this portfolio. For many years I felt that the arts in Penang have become merely just an element to feed the tourism industry, and the contribution of the arts is not respected but exploited.

MC: Of course, your audience is also going to be largely tourists, so it’s going to be interesting for them to come and have to look at themselves critically.

B: There’s also the fact that most visitors will just come seeking backdrops for their quest to selfie, which is perfect. That’s when I can criticise them in hidden layers. It’s like a trojan horse.

MC: Are you happy, then, for people to not ‘get’ your work?

B: It’s fine with me. I’m providing to those whom this may concern, beyond that is bonus. I’m happy to be able to do this.

MC: You have used the term ‘remastering’ to describe your way of working – going back to old works and re-making them. You’re really screwing with the whole ecosystem of the art market in that way!

B: This act of remastering applies only to works that are not already sold – works that are still in my possession – that I see still have room for improvement or better polish. Buyer’s approval is the least of my concern, I’m not producing new world wine.

MC: You are also taking away the idea that a work of art is important because it is unique, because it’s the only one, a single moment in the history of an art practice.

B: I suppose I am doing that too. Nothing is infinitely permanent anyway. But the idea of remastering is not a total transformation of the original, but better enhanced version.

MC: I suppose street art completely gets rid of any of these artificial art market ideas. It exists for a while, then it’s gone. And you can’t really buy it to have it.

B: Yes, street art gets rid of the market aspect of ownership transformation, but financial transition still exists in commission projects. To say you can’t have it is also not exactly true in the case study of a Banksy piece being cut out from the street and placed into auction.

MC: So you are happy for your work to be either deteriorate or be disposable?

B: Deterioration is inevitable, it’s just the matter of prolonging. The pyramid of Giza lasted for centuries long but it’s not the appearance of how it looked when first completed. Disposability relies on value, found object installations tend to suffer the most because there is no clear obvious stereotype indication that it’s an object of art. So, with this notion in mind, it all falls back on the intention to what extent the owner wants the art object to be preserved.

MC: They do say that you can be way more creative when working within a set of boundaries than if you have free reign. How do you feel about that?

B: What just happened to think outside of the box? Having a set of boundaries helps to stay relevant, having free reign could potentially get lost and confused, but it opens up previously unaware perspectives.

MC: Can I ask you what is next for your practice?

B: As I am preparing for the upcoming solo show, I am also exploring wooden sculptures for the show. I’ve been learning wood sculpture on and off throughout the years, but for this show I have the need to speed up, a friend recommended an oscillating saw and it’s been a great help.

MC: I was wondering if you could characterise the art scene here in Penang, compared to maybe KL, or other places that you’ve been?

B: Looking from the outside, Penang or George Town is seen as an art city. State government has been promoting the island as an art hub. But in an over simplified term I would describe it as Gua Tempurung – looks great on the outside, empty on the inside. Historically, Penang was one of the two pioneers in the Malaysia art movement – we are known for the Nanyang art movement – our former glory has expired, and the contemporary art movement is struggling to self-sustain. One prominent collector once advised me, “stay here, produce here but sell elsewhere”. A decade later, the statement still applies.

MC: Talking about the art scene, my final question is to ask you to give me some names of artists who you find inspiring, your contemporaries, who you think are doing really good stuff.

B: I’m not sure if he is keen for an interview, but I suggest Hoo Fan Chon. He’s a KL-born, Penang based visual artist. He used to run Run Amok gallery some time ago, the gallery used to practice something similar to PechaKucha, getting local artists to introduce their practice or findings to each other. The gallery shut some years ago and now he focuses more on his own practice. He’s one of my self-declared mentors, who I bounce ideas off.

I would also recommend Ivan Alexander Francis Gabriel; he is both independent and in-house curator/manager of Hin Bus Depot Gallery. Ivan came from a theatre background. He also practices sculpture, making tiny mushrooms and fungi. He brings in lots of quality shows for Hin Bus Depot for the past two years.

Then Kenny Ng of Penang Art District, he is the one man show conductor that ties all arts together under one umbrella. He used to have a team that covers the whole Penang state, providing supports in term of resource-sharing, equipment support, manpower sourcing, promotion assistance, producer support, sources for funding, cross-partnership between corporations with art projects, venue activation and more. They also come up with pivotal programmes like the annual Spotlight competition for visual art in which winner will be paired with a mentor in preparation for a solo show; and the Kecik-kecik Group Show that functions sort of like a small scale art expo to encourage new young art buyers, and a trial platform for artists who lack the opportunity to experience exhibiting and selling their works in public. They used to host art writing workshops and gallery sitter training programs. Unfortunately, since late 2023 the state decided to completely defund them, shrinking an already understaffed team of 3 to now just Kenny alone running PAD with public donation, totally stunned by the 8 years effort of PAD’s attempt in nurturing the art scene. PAD is the only state agency that, without prejudice, covers all art forms from theatre, music, performance art, visual art, traditional art, digital arts and so on.

Leave a comment