MC: I’d like to ask you first to talk me through your degree show exhibit.

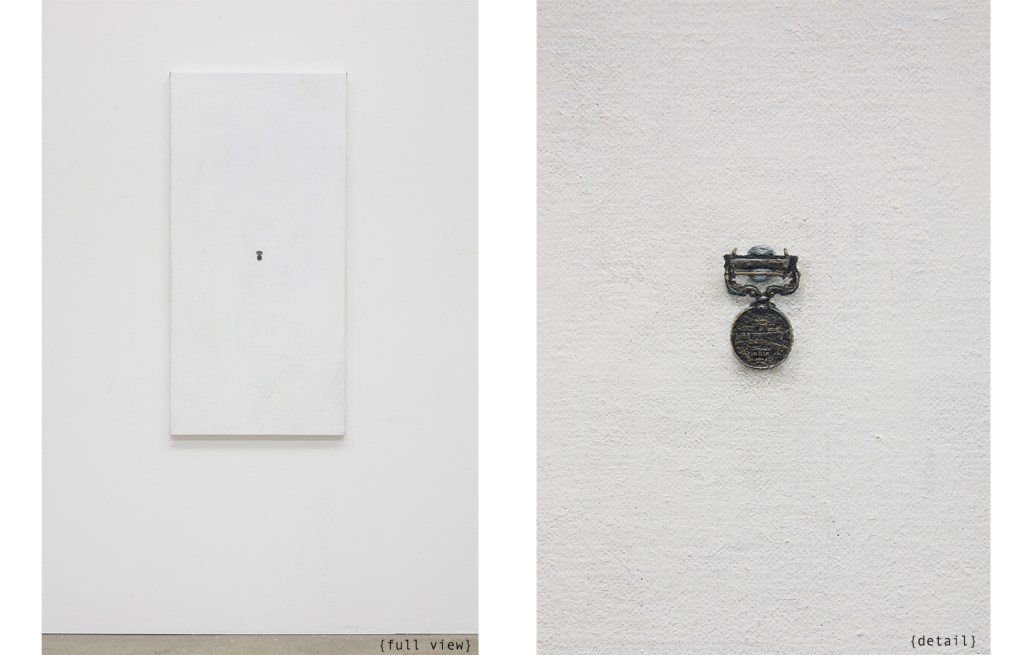

ED: You saw the three paintings, and the first of those three to be painted was the one with the medal. It has two titles: ‘1919’, and ‘Evening Light on Jamrud Fort’. It’s a service medal from the 1919 Anglo-Afghan war, which emerged from my grandmother’s belongings when we were clearing her house. It is one of several things in the house that told me about our British colonial background, which is quite a heavy and complicated thing to engage with. That object has been kept in a relatively uncritical way, in a kind of loving and interested way I think. It’s an interesting historical item, and it has been kept to tell me who I am, and future generations too. But then I look at that and think, oh God, that’s who I am! Not necessarily this straightforwardly interesting thing that it was possibly intended as.

It’s a strange thing to sit with, and I don’t want to be simplistic about it. I come from a generation who’s attitude toward British colonialism is very different to the ones before, and I definitely share those feelings that it was generally a terrible thing. But that doesn’t necessarily mean that the people who were going to these wars, or had these jobs, on the boats across to India… they were just people, going where the jobs and husbands were, but were also cogs in the machine of something, as I see it, very sinister. I’m sure there are things that I’m doing now that, generations from now, people will look back on and think were sinister. It’s not straightforward. I think that painting is a good way to sit with something like that for a long time without necessarily coming to a definitive conclusion. Especially the way that I paint, which is very slowly.

MC: That’s very important. I think that our generation can often be very naïve and kind of blinded by the time that we’re in – we tend not to think about the people involved in the past, or what will happen in the future. Painting is a good way to reckon with this, because it’s an object that will remain beyond our human lifespan, as an heirloom of this moment, into the future.

ED: Totally, painting has such an intense and specific relationship to time. It’s an image that is made over a period of time, it reaches back into long traditions of painting, and reaches forward as you say. The other thing about painting is that it really locates me firmly with the object and the experience of being in the moment. Through that, I am putting the issue behind the picture plane, away from myself, so it’s a kind of positioning which is both embedding me in a world and also holding it at bay. I think that that happens in a temporal way – it’s a kind of connection to the past but also a commitment to the present and future.

MC: So a critical distance, in a way?

ED: Sort of. Critical distance, but with the awareness that you can’t ever really have that! Critical distance and total biased embeddedness as well.

MC: The fact that you’re using family heirlooms is very interesting. But the format of the painting too – this really tiny medal on a large white background, very realistically painted – how does that figure?

ED: It came about through various different reasons. I stretched that canvas up with the intention of painting a more conventionally-composed scene with a figure, but I sort of felt that it wasn’t quite right. In fact, I started painting it and then painted over it – so, again, another element of time layering. I think it’s to do with giving it space to resonate. I did the painting in order to give myself space to think, and that is reflected in the literal space around the canvas. It also comes from a series of paintings where I have been painting on the wall. I’d hang the object on the wall and have a canvas next to it, and I’d replicate the object and the wall. Gradually I got to the point where I was putting the object directly on the surface I was painting on – so the surface, instead of representing something outside of itself, it just represents itself. But it still had the memory of the wall in it. I pushed it further and further. I did some paintings where the object filled the entire space, and then I started to make things small to see how much space you could have around the object without over-balancing – turns out, loads!

MC: It’s such an interesting composition because it’s to-scale, right? It’s as if you’re trying to not take any artistic liberties at all when representing this kind of volatile object.

ED: Yeah, that’s a good read on it. I often find myself trying not to take artistic liberties. It’s bang in the centre as well, it’s as close to ‘neutral’ as possible.

MC: You seem quite worried about your positionality when you’re painting?

ED: Not worried, exactly, about positionality, but I feel that that’s the whole project. The purpose of painting, for me, is to work out my position in the world, to locate myself, and to come to terms with things which are difficult.

MC: You’re very aware that painting is not a neutral act, it’s a political act – but you’re using very classical methods. You’re the most classical painter I think I saw at the RCA Degree show. You use life drawings, all the artist’s tools. Where does this come from?

ED: My background is that I did an art history BA, and found that my ideas were kind of outstripping my technical ability. A friend of a friend was at a traditional atelier classical-type place, and I went to do a short course there. Actually, it was my dad who encouraged me to go and see this place, and initially I thought it would be so boring and old-fashioned. And then I went and I just loved the intense technical discipline of it. It was so uncompromising and so strict, and the standards that they got out of people was so high, I felt I just had to be there. I was then there for three and a half years.

I did find that tricky. It was very much a technical training, not a theoretical one at all. Talking of critical distance – there was none of that. No engagement with the weird fact that we were being trained in a 19th century technique in the 21st century, and a technique which was borne of empire in the most literal sense – in the sense that it’s classical.

MC: And the act of just looking, when you’re learning to draw from observation like that. It is a power play in itself.

ED: A hundred percent. You’re all in the life-room, all the artists are in the dark behind their easels, fully clothed, looking at the model who’s naked in the light – all of this. None of it was ever really examined or discussed. Phrases like ‘truth to nature’ were used, with no questions of who’s truth, and what is nature – crucial questions.

I’d got my teeth into the technical question, and I wanted to finish the course. But I have basically spent all my time since I finished there wrangling this strange clash of how I think and how I now see. Because it does change how you see, that kind of training. It is violating in a way. It does feel that, in order to get as good as you can be, you have to allow yourself to become a nothing. Let the tradition work through you. So you’re letting all these dead white men enter you and work through you. I found it quite spooky – especially when I was painting things like the Venus sculpture, which is so loaded. I think that now this is both a really amazing and useful thing, and a problem – a generative problem but a complicated position to be in.

MC: It’s a fascinating problem to grapple with, and it’s something that I don’t think a lot of people are thinking about, the classical tradition. I guess because it’s not popular to paint in the classical tradition.

ED: Yeah, it’s not a problem that a lot of people have because they just don’t bother with it. A good way of doing it!

MC: Kind of bypassing the issue altogether by going super abstract.

ED: I often wonder why I didn’t want to do that. I think I believe in craft. I really think that craft is a valuable thing to do. And I also believe in really looking straight at what it is… I mean, it’s extreme, but it feels like an extreme version of what would be happening anyway. I’ve already been brought up with the Western canon, I’ve already been brought up with that white British colonial past. I think that learning to paint in this way is a way of really examining that gaze – by making it such an intense and sharp gaze. I guess you could say that that’s stupid because you’re just leaning into it. But it’s about accepting who you are and really looking at it.

MC: It’s really important. In terms of decolonisation, it’s something that is often forgotten about – to look at where you yourself are and think about it deeply!

ED: The other thing is that representational painting has a particular relationship with the world which works for me. I’ve never really had an abstract sensibility. I can appreciate other peoples’, but whenever I do it… it doesn’t have the teeth that it needs.

MC: But talking of representation, I’d like to move on to the other works in your show. You’re playing with media and the idea of something being ‘true to life’. I’m thinking of the painting which is just of masking tape stuck to a wall, kind of like an empty studio that has just been vacated. And then you had a painting of a photograph which is pinned to the wall.

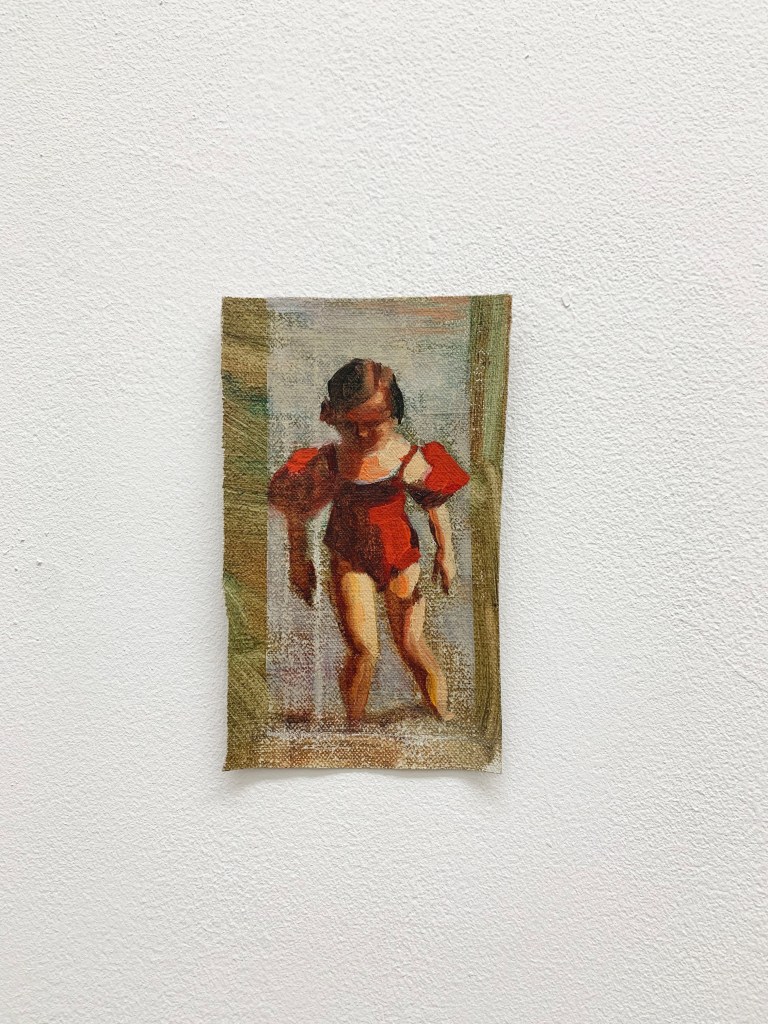

ED: The painting of the photograph is also explicitly family-based. It is a painting of a photo of my aunt when she was very little. She died before I was born, but a long time after that photo was taken. It was taken in Hungary. My grandfather was from Hungary, had to flee there during the war and married an English wife and had three kids including my mum and my aunt Sophie, who is in this image. She has just been swimming in the Danube, and she’s coming up the bank towards us. I just found it a very poignant photo, just on the edge of that threshold, just out of the water. Of course, with the Danube having such an important historic place. In the show, that was hanging just on some masking tape.

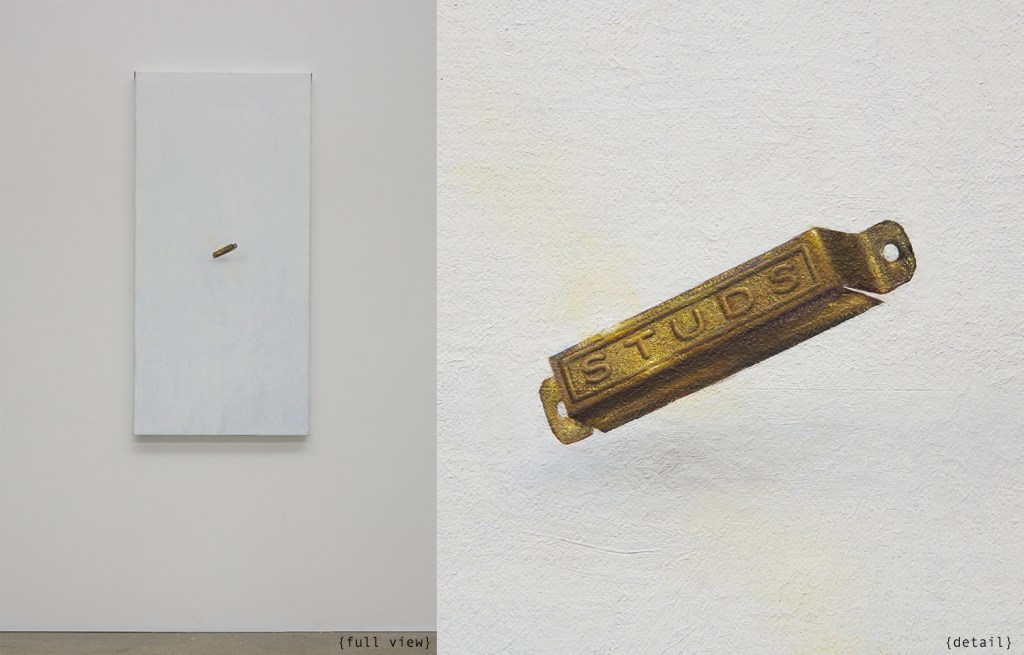

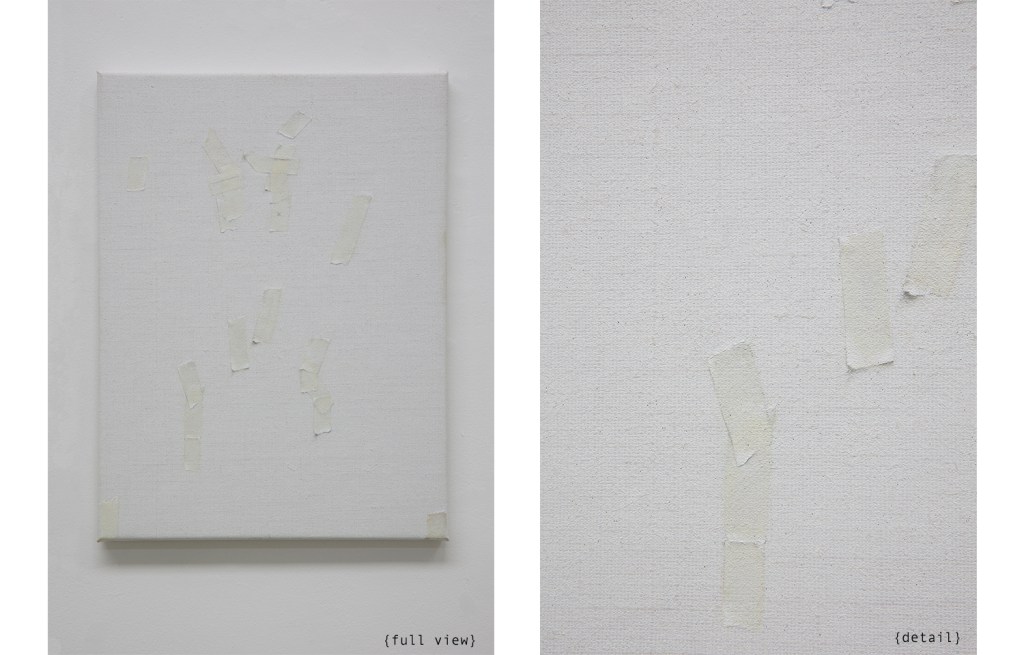

Next to that, there was a trompe-l’œil painting of masking tape on a board. The masking tape on the board came from a traditional approach to life drawing – using masking tape to mark where a model is sitting, so that when they can get back into pose, they can find it again easily. My partner was sitting for me with their arms on a board, and I used the tape around their arms to locate where they were. Then they went off to work or whatever, and I was left with this board, which suddenly seemed like an interesting object in itself, in the abstract way but also in terms of having the trace of a person.

I think trompe-l’œil is a lot of fun to play with, because it’s easy for a lot of people to enjoy it. You don’t have to know much about art to be like, ooh it looks real but it’s not! And that’s an entry point.

MC: It’s a very intimate painting, too, as it’s a portrait of your partner in a way. And this idea of the missing person, in terms of the archive, is very interesting. I think the three paintings work together so well because the objects in all of them are a stand-in for a person who’s gone, these family heirlooms and this palimpsest painting with the tape. Maybe now is a good time for you to tell me more about this archive-box you’ve brought with you here?

ED: I worked as an archivist for the Royal Watercolour society for a long time. It was an insight into how archives work, and often how archives don’t work at all. That was a really quick realisation that these things which have this appearance, or apparent structure of clarity or completeness and logic are so dysfunctional and changeable all the time – and so violent, in different ways. So, this is a kind of take on the archive, I guess.

MC: It’s interesting because, even though we both know that the archive is this false thing, the whole vibe of an archive is so aesthetically-pleasing and romantic – things wrapped in paper and kept delicate…

ED: That’s the thing, isn’t it? That’s the enchantment of it. Would you like to have a go at it? Doing the unwrapping is part of the fun.

MC: Where did the box come from?

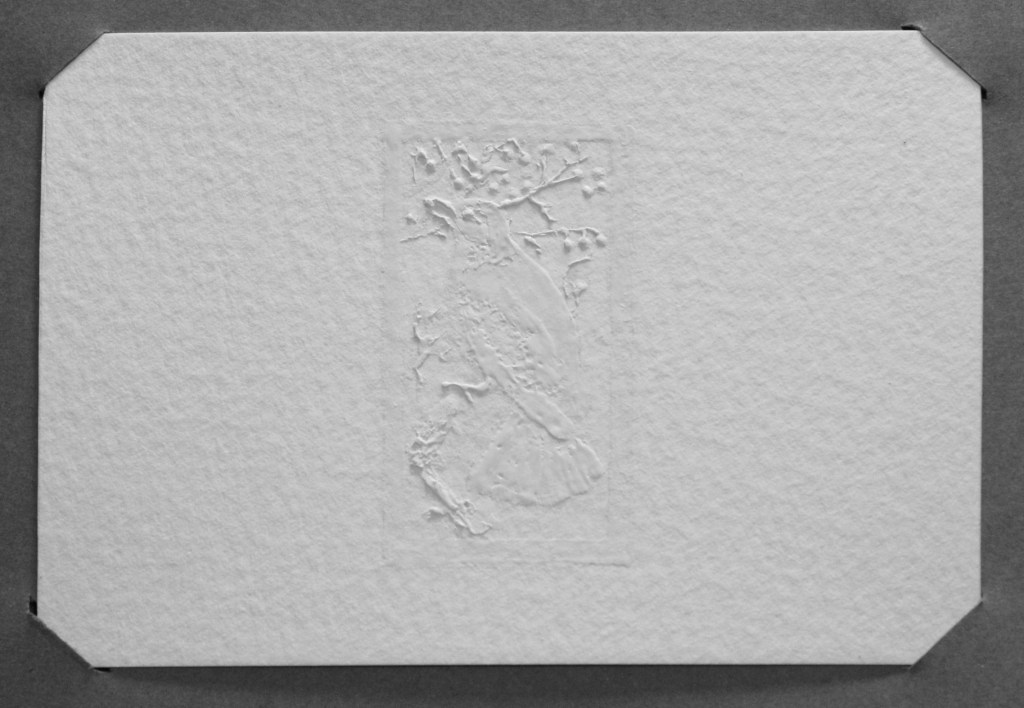

ED: I made it for this project. The box has several booklets in it. Are you familiar with the idea of tea-cards? You used to be able to collect these little cards which you’d get from packets of tea. This was a series of British birds, a series of fifty cards which were painted by a Royal Academician. These are my recreation of those cards, to scale, which I painted in white gouache on watercolour paper. I definitely lifted a lot of the material language of the RWS archive for this project. The grey of the booklets and the specific green buckram of the box.

MC: It’s perfect because it’s so simple but so visually impactful. So, what does the visual language of the archive mean to you? Is it something you would like to explore further?

ED: I don’t know how much it is going to continue as an explicit theme in my work – I mean, it probably will. It’s bedded-in now and feels like it’s inherent in my work. These are ways in which we enchant objects and images, aren’t they? I was so aware of that when my grandmother died and we were looking through her things. She was such a historian and an archivist. Everything was labelled, and she had a family tree on the back of a painting saying who this is of and who owns it, and that sort of thing. I guess I’m interested in the different ways in which that enchantment operates. I don’t know if the specifically archival material is where I’m going next, though.

MC: It seems to me that the personal, family archive is something that you’re interested in, in terms of objecthood. But I wonder if you’ve grappled with the idea of the archive as being false in relation to this series that you’re doing of the objects hanging on the wall? The idea that they represent someone else’s creation of what truth is?

ED: Totally, and that is something you encounter a lot when you are either working as an archivist of someone else’s archive or clearing someone’s house when they’ve died. You become very aware that these are things that have been selected to be kept. Then, what do you select to keep? How do you operate within these things, and what meaning do you create by the structure of how you keep them? I think archives are very capricious things that pose as the opposite.

MC: Yeah, they pose as the basis of the neutral idea of truth – of saying ok, the proof is here, you can’t argue with that!

ED: That’s the interest for me, that falsehood. This idea of having fifty British birds. It’s charming and sweet, in a way, but it’s also bonkers – the idea that birds have a nationality, that there are fifty that you can collect. It has all this association with egg collectors, trophy hunters and the colonial histories of tea.

MC: And also playing with the idea of British identity, like what you were doing with the medal.

ED: Painting, for me, is a way of archiving in the sense that it is putting into prominence different things. My grandmother always used to be getting out a box of things which were perfectly well-ordered and going through it again and getting rid of some things, and photocopying other things to put in other boxes, and reordering, and writing little labels… Something I realised when I was working in archives was that it was a constantly moving thing, and I guess painting is a bit like that too. You’ve got all these things and you’re moving them around. That’s one metaphor. I think archives are a useful metaphor and device, but I think sometimes they get overloaded with meaning and significance, and sometimes you need to break out of that metaphor as well.

MC: Archive fever, exactly! I’d like to ask you to step more into the world of your studio practice. When you’re working with these objects, how does it feel? How does it work when you’re coming up with the conception of a painting? Are you someone who sketches? What’s your process?

ED: It’s quite varied and I want it to stay quite varied. When I settle down to do a particular kind of painting I might know the arc of it. Although I have this very traditional, set way of doing things available to me, I still want to keep in that element of chance and changing my approach. For example, that little painting of the photograph of my aunt – that was going to be a study for a painting on a much larger canvas, the same format as the medal. Then I changed tack. So, there is a process for making a big painting which I have been taught, which involves doing colour studies and sketches and working from life and scaling it up. But I deviate quite a lot.

MC: It shows in your work, in that the traditional processes of painting that you learned on this course – it becomes part and parcel of the actual subject of your work. The masking tape painting, these small studies, the idea of studio practice – these things seem to become a subject in themselves.

ED: Totally. I think being present in the studio is a big part of that, and being alert to what is happening around you. You’ve got to keep your eyes open and notice, maybe, I’ve accidently pinned this sketch on the wall next to this thing, and they sort of activate each other in an interesting way. Or perhaps I’ve got a colour study, and a sketch, and a transfer drawing of that sketch, and then the final painting. So, I’ve suddenly got all these iterations of the same image happening at once, echoing around the studio. And then, what do you do with that? Do you try to translate that into some kind of final presentation, or just leave it as a studio experience?

I think the thing that is universal amongst the different ways in which I work is that I always start with a problem. Something that I don’t understand or that I need to figure out. And in the process of trying to figure it out – which I rarely do – I produce these side effects which are paintings. I’m trying to work out how to work from life again, because I’ve got a definite training in that. I can definitely approach that from a technical perspective, but emotionally it’s complicated because of this strange power dynamic that you have. I’ve learned to have a kind of mutuality with objects within the space, but a person is so much more complicated.

MC: The encounter with an object is simpler, because you’re not in danger. You can manoeuvre an object. A person can bite back.

ED: And the duty of care is vital as well. You need to make sure they’re comfortable and have ways of coping with that quite extreme intimacy that you’re doing. I teach life drawing, and you have all these formalities in place, and weird little dances that you do to make the model feel safe. Those are all things which diminish the intimacy, which is appropriate for that setting. But for my own work I want to take those risks and go deep, but I have sometimes found that I’ve overstretched, and we’ve suddenly entered this very intimate moment and I don’t really know how to hold myself and hold them in that moment.

MC: I feel that the practice and the tools that you’ve already developed are going to be perfectly placed to explore that idea in a critical way. This idea of distance, against the intimacy of the masking tape painting, for example. I’m excited to see what you’ll come up with.

I’ll ask you my final question. I’m looking for three names of contemporaries, people whose work you have an accordance or resonate with?

ED: I might have to go away and think about it, because there are so many artists whose work I admire, whose practices have influenced me. I’m going to ponder it and get back to you . What I will say is that I’ve got a show coming up in early November with one of my good friends on the RCA course, Julian Eleison, whose work is about as different to mine as you can imagine, and it’s great!

Edith’s three artists:

- Rita Fernadez

- Sa’ad Choeb

- Jake Lamerton

Leave a reply to Ruth Dormandy Cancel reply